“Friday 24th [February, 1804]…I am very Uneasy about [Joseph] Boisvert and [Jean] Connor. It is now nineteen Days since they left for the fond du Lac, expecting that it would take Twelve Days To make The trip. They carried one fawn-skin of rice almost full for provisions to the fond du Lac. I wish I could find some savages To send with [Gardant] Smith. I don’t know what to Think, whether they are lost either going or returning…” (Curot, 443)

Mosquitoes flew from clumped grass. The wispy insects hovered and drifted in the afternoon’s gentle breeze, but made no attempt to land on my hands or face. At the edge of the clearing, my soft elk moccasins struck a well-used doe trail, the one that led to the east side of the spring-fed watering hole. Clad in linen and leather, I kept to the shadows, amongst the tall cedar trees, out of sight.

“Jay! Jay! Jay! Jay!…” Blue jays screamed from a distant oak; to the south, other jays chimed in. Even from their lofty perches, I doubted the ruckus had anything to do with a traditional woodsman making his way through the understory, searching for signs left by two tardy hunting companions.

“Jay! Jay! Jay! Jay!…” Blue jays screamed from a distant oak; to the south, other jays chimed in. Even from their lofty perches, I doubted the ruckus had anything to do with a traditional woodsman making his way through the understory, searching for signs left by two tardy hunting companions.

My moccasins skirted a patch of milkweed, now nothing but dry, brittle stems. A sudden gush of crushed wild mint filled the air. A few footfalls later I walked around a bushy wild rose with long green tentacles festooned with a thousand razor sharp hooks. A short while after that my course gave distance to a bald-faced hornets’ nest, tucked head-high within the boughs of a modest cedar tree. It was a pleasant fall afternoon, in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

At the southeast corner of the small pond, my nose caught the first smell of death. Without conscious thought, I dropped to my knees in the tangled canary grass and spent the next few minutes surveying the swamp while sniffing the air. The westerly breeze toyed with my senses, first bringing the pungent stench, then whisking it away. All manner of atrocities filled my imagination.

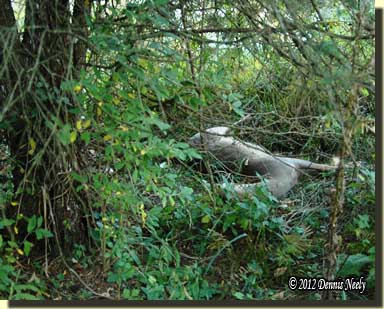

As if stalking a magnificent stag, I proceeded to cross the swamp, following a familiar trail. Pearly-white clam shells, opened skyward and cleaned of their inhabitants, littered the mucky bank. The putrid, greasy smell of rotting flesh grew stronger with each moccasin step until it became almost unbearable. My heart pounded with trepidation as my eyes inched through the grass and raspberry patches along the bank. When I saw the dead doe, relief flushed over my being as I gasped for fresh air.

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD)

Thirty or so counties in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula are currently experiencing an outbreak of epizootic hemorrhagic disease. Unfortunately, the North-Forty is impacted by this horrific epidemic.

EHD is a devastating viral disease found in wild ruminants (mammals that have an internal, stomach-like organ known as a rumen and who chew a “cud”) like white-tailed deer. The infection is fast-acting, coming on within seven days of exposure; usually within two days of the onset the infected deer is dead. The infection is transmitted by a tiny, biting fly called a “midge,” and there is no known treatment or method for controlling EHD, other than a hard frost or freeze that kills the midge.

For the victim, there is an immediate loss of appetite accompanied by a loss of the fear of man. The deer grow weak; the pulse and respiration rate increase, the animal starts salivating, and a fever sets in. To relieve the fever, the animals seek water to reduce body temperature, which is why many EHD deer are found in or near water. Excessive hemorrhaging characterizes an infected deer. Veterinarians tell us EHD does not affect humans.

Beyond a Fair-Chase Hunt

One of the three key elements of any traditional black powder hunt is a dedication to fair-chase ethics. The cornerstone of fair-chase hunting is a steadfast commitment to respecting the game that frequents any history-based scenario, and an integral part of that respect is a deep feeling of responsibility for and dedication to the general welfare of all woodland creatures. A prime example of this respect was displayed last June when a newborn fawn was discovered at Station #3 during the Traditional Muzzleloading Association’s “Old Northwest Frolic.”

Finding the first dead doe on the North-Forty radically changed the fall’s priorities; traditional squirrel hunting seemed of little importance. Like most folks, I have limited hours to devote to hunting. When the health and well-being of the whitetails that frequent my 18th-century Eden came into question, the allocation of those hours shifted.

Finding the first dead doe on the North-Forty radically changed the fall’s priorities; traditional squirrel hunting seemed of little importance. Like most folks, I have limited hours to devote to hunting. When the health and well-being of the whitetails that frequent my 18th-century Eden came into question, the allocation of those hours shifted.

With the discovery of each new carcass, the feelings of utter helplessness intensified. I have come to dread gazing into the dulled, brown eyes of an infected doe as she lays a few feet away, but there is nothing man can do to stop the spread of this horrible disease, or the inevitable outcome. And in a strange way, stumbling upon another carcass fuels an overpowering need to look further, to expend time that simply doesn’t exist. The veterinarians are quick to say “EHD does not affect humans,” but although that is true in a physical sense, it does not address the mental anguish of those who accept stewardship of these beautiful animals.

A “Different” Hunting Scenario

The first night I started walking the big swamp, my mind slipped into the 1790s, out of habit, I suppose. I had on grungy jeans, a green denim shirt, leather hiking boots and I wore my blaze orange National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association ball cap—a far cry from 18th-century linen and leather. In hindsight, I believe the emotional intensity, and yes, distress, of searching for EHD deer, not wanting to find them but wanting to know, allowed my mind to do what it does on most sojourns—travel back to my favorite bygone era. And to be perfectly honest, sometimes time travel becomes a safe haven from the tribulations of 21st-century existence.

As I followed the crossing trail at the south edge of the watering hole, the same path followed a few days later on that September afternoon, my mind recalled Michel Curot’s concern for his men. I couldn’t remember Boisvert’s or Connor’s name; I had to look up the passage when I returned home, but I knew the gist of the words and I thought I had a sense of the emotions. With each footfall through the brittle sedge grass, my mind fleshed out a stark woodland lesson plan for my wilderness classroom: a nerve wracking quest for overdue hunting companions.

In pondering the thoughts of that first evening, I realized that here is a “different” type of hunting scenario, one that centers on the harsh reality of 18th-century life. Years ago, when I chose the path to yesteryear, I did so with a burning desire to gain firsthand answers to one specific question: “What was it really like to hunt, survive and live in the Old Northwest Territory?”

Sometimes those answers are not the answers that we want to hear, for death walked but an arm’s length away from most of our hunter heroes. Hidden in Curot’s “…I don’t know what to Think…” is the strong possibility that either Boisvert or Connor or both would never return to the trading post. Such was the fate of so many 18th-century folks, including John Tanner whose final chapter is unknown.

So many times my hunting scenarios focus on a passage from an old journal that relates a hunting adventure. In the past I have tended to skim over the “unpleasantries,” not because I am not willing to face the gruesome facts of woodland life, but rather because I have so few hours to devote to traditional hunting—I simply must choose the scenarios that fit the time allotted. Yet, there is a silver lining to every dark cloud.

I am told that the stench of human decomposition is different from that of an animal; fortunately I do not have firsthand knowledge to share. Once immersed in this type of historical scenario, regardless of geographical region, time period or circumstance, the slightest whiff of death triggers an emotional trepidation that fears the worst. I experienced such trepidation on that pleasant afternoon in 1795, and therein lies the worth of pursuing such a scenario, for it offers a few fleeting seconds of oneness with the fears, the heartbreaks, the horrors of our hunter heroes.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to The Search for Lost Companions