Killing lost its luster. Canada geese ke-honked above the tree tops. Cranes chortled to the west at the River Raisin’s sandy flats. Two blue jays screamed to the east, at the corner of the nasty thicket, near the barberries. In time, five black-capped songsters populated two witch hazels. “Chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dee… chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dees…” Their rousing chorus filled the 18th-century forest that fine October morn.

Then a young fox squirrel spiraled down a red oak. Its little black claws scratched the rough bark as it advanced earthward. The first bounce into the dry leaves was loudest. Dirt and duff flew as this forest tenant searched for a breakfast morsel. Little did it suspect a Northwest gun, charged with a swarm of dormant death bees, rested across a returned captive’s bare thighs.

Not long after, a second fox squirrel appeared on a hickory’s lower limb, some distance to the south, well beyond the smooth-bored trade gun’s range. This squirrel lingered in that tree with no apparent reason for its deliberate comings and goings from branch to branch. The creature’s bushy tail flicked and flitted with a nervous unending twitch. Several times it slipped behind the shag-bark’s modest trunk as if uncertain where to go next.

A gray squirrel, displaying the opposite tendencies, descended a good-sized red oak on the sunny side. Sitting upright in a sunny spot, its tail curled against its back, the little beast surveyed the forest floor. A gentle southwesterly breeze carried fall’s magnificent  tannic perfume. The gray made no noise as it bounded off in the direction of the elongated scrape beneath the ironwood that grew near the hollow sassafras.

tannic perfume. The gray made no noise as it bounded off in the direction of the elongated scrape beneath the ironwood that grew near the hollow sassafras.

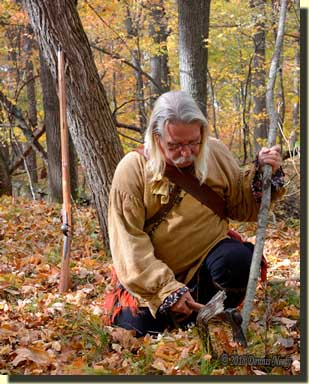

Supple saplings suitable for bending to form a wigwam occupied my mind that morning. One lurked to my right. Nestled among others, towered over by a keg-sized red oak, that sapling would soon meet its end.

After getting to my feet and leaning the Northwest gun against a nearby sassafras, the ax slipped from the sash that bound my weathered, yellow-dyed linen shirt. Two swift strikes toppled the cherry, leaving a chisel-like point. With the sapling’s base held firm in my left hand, the blade skittered to the right, cleaving thin branches flush with the trunk. In all, twelve culls of varying sizes suffered the same fate.

Tiny Steps to Future Success

About every other year I set the goal of building a period-correct shelter to act as the center for that fall’s traditional hunting adventures. Current research usually inspires the camp’s design, and the dominant persona I intend to use has a great influence on the shelter’s style. Some years I achieve that goal and some I don’t. In the latter instance, a prior year’s camp is usually available, either for use “as is,” or to modify to fit the circumstance.

But on a clear day in the spring of 2014, a stout limb fell and flattened the Meshach Browning “cedar brush camp,” removing that possibility in a rather scary manner. In addition, only the rafters of the “mallard duck lean-to” in the cedar grove remained, plus the camp did not suit my emphasis on Msko-waagosh’s returned native captive persona.

As so often happens, too many life commitments consumed the summer. Faced with no usable option by late September, I rolled out my blanket wherever I pleased, just as I expected John Tanner did, or would. As 2014 drew to a close, I swore 2015 would be different.

Constructing an Ojibwe wigwam for the 2015 fall hunting seasons held a prominent place near the top of this living historian’s “to-do list,” along with spending as many days afield chasing wild turkeys or white-tailed deer as possible. When Darrel Lang and I planned that day’s sojourn, I told him I intended to start on the wigwam, rain or shine.

Later that morning a British ranger hunting out of Fort Detroit joined me as I leaned the saplings against an oak. When I vacillated on the shelter’s location, Darrel suggested an alternate spot, flat and sequestered. We went to work marking out the location of the twelve poles, driving a stake to make the hole in the soft earth to receive each sapling and selecting the right-length pole for each bent.

Later that morning a British ranger hunting out of Fort Detroit joined me as I leaned the saplings against an oak. When I vacillated on the shelter’s location, Darrel suggested an alternate spot, flat and sequestered. We went to work marking out the location of the twelve poles, driving a stake to make the hole in the soft earth to receive each sapling and selecting the right-length pole for each bent.

When we started bending and lashing saplings, the crooked culls fought our efforts. Nice straight saplings would have worked better. The arches were not as uniform as I would like, and a couple broke, which slowed the wilderness classroom lesson. I know Tanner’s family would have axed prime stock, but I can’t bring myself to cut a good young tree that someday might make a fine saw log.

As mid-afternoon approached we left the half-framed wigwam and returned to chasing wild turkeys in earnest. The wigwam project sat idle for almost three weeks—more demanding circumstances took precedence, just as they had the year before.

The next opportunity to work on the wigwam came the weekend before Michigan’s firearms deer opener. I asked two of my grandsons if they would like to help. Msko-waagosh overlooked their camo coveralls. Late-eighteenth-century, youth-sized trade shirts, leggins, breechclouts, moccasins and silk head scarves found their way onto papa’s ever-growing “to-do list.” Nightfall ended that outstanding wilderness classroom session, much to everyone’s disappointment.

The next opportunity to work on the wigwam came the weekend before Michigan’s firearms deer opener. I asked two of my grandsons if they would like to help. Msko-waagosh overlooked their camo coveralls. Late-eighteenth-century, youth-sized trade shirts, leggins, breechclouts, moccasins and silk head scarves found their way onto papa’s ever-growing “to-do list.” Nightfall ended that outstanding wilderness classroom session, much to everyone’s disappointment.

Late in an afternoon during the first week of deer season, I finished lashing the horizontal saplings to the bent poles. I started fitting canvas to the frame. The rectangular canvas did not fit the arched contour well. The second piece went up better. Then I realized that if the wigwam’s diameter was about a foot smaller the canvas pieces would fit much better, but it was too late to start over. The intent was a one person shelter, and what I ended up with is adequate sleeping space for three adults. Again I ran out of daylight.

Unlike last year’s dreadful cold, this fall’s weather was mild and pleasant. I couldn’t get enough hours in my 18th-century Eden. Additional demands for my time, driven by the unseasonable weather and circumstances totally beyond my control, gobbled up hours allotted for pursuing whitetails. I made the best of the situation. I don’t regret those choices, but it was at the expense of finishing the wigwam.

Despite accepting life as it is, the historical me still feels a sense of disappointment and deep frustration. Yet, I learned a tremendous amount from the wilderness lessons that surrounded the wigwam, and there is an offsetting degree of elation that accompanies that gain.

I share this experience and reflect upon it, not because it represents a failure, but rather because it demonstrates the tiny steps that are sometimes required to inch closer to a future success. For traditional black powder hunters so many of the lessons learned and so much of the knowledge acquired is based on trial-and-error, hands-on participation in a woodland setting orchestrated to simulate, as close as possible, one recorded in a centuries old journal entry. Again, sometimes we, as living historians, achieve our goals, and sometimes we do not.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

3 Responses to Sometimes ‘Yes,’ Sometimes ‘No’