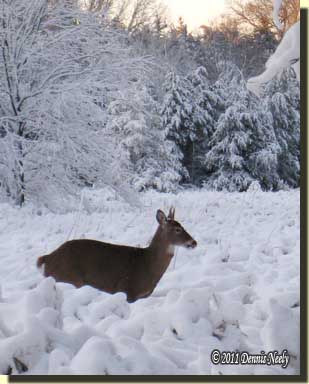

A deer’s head bobbed up in the poison sumac and marsh elders. Its ears flicked front to back to front. It looked side to side displaying noticeable concern, then disappeared in the thick wet snow that clung to every twig and branch. In a minute, a second deer’s head appeared in the same spot. It looked about, but displayed less caution before vanishing. Well beyond the Northwest gun’s range, the deer teased a patient woodsman.

It was mid-December, in the Year of our Lord, 1793. The night’s snow tempered the fall’s unseasonable warmth. The air smelled clean, but heavy with moisture. Every bush, every bough drooped from the snow’s weight, forming an impenetrable curtain that worked both for and against the deer.

Now and again a white clump fell earthward, some broke apart in a crystalline shower while others thumped hard. When the first deer’s head popped up, I stood still. After its head dropped, the scarlet trade blanket that covered my left shoulder pressed against an oak trunk as I waited for the latest woodland scenario to play out. Although snow splattered the blanket’s folds, I was as vulnerable to detection as the deer were, yet Nature’s white curtain protected me, too.

Snow melted on my cheek as I watched the thicket, hoping for a fine buck to follow the two does. Uphill a bit, a crimson cardinal tried to perch on the tip of a cedar bough, but the little songster started an avalanche. The cardinal flew straight up, hovered, then looked down in wonderment before choosing a wind-fall oak limb.

In due time my winter moccasins advanced. I followed the trail at the edge of the big swamp and headed south, taking single steps, then pausing. That morning’s still-hunt coursed around a little bend. During a pause, a patch of brown hair moved in the shadows of the cedar trees on the far bank. I watched. A foreleg stepped; a hind quarter followed. In a few minutes, a deer emerged, maybe 80 paces distant, sporting two graceful spikes.

In due time my winter moccasins advanced. I followed the trail at the edge of the big swamp and headed south, taking single steps, then pausing. That morning’s still-hunt coursed around a little bend. During a pause, a patch of brown hair moved in the shadows of the cedar trees on the far bank. I watched. A foreleg stepped; a hind quarter followed. In a few minutes, a deer emerged, maybe 80 paces distant, sporting two graceful spikes.

The young buck showed the same cautious nature as the first doe, pausing as I paused, looking around as I had. It walked through the dead golden rod sprigs and stepped into the sedge grass, choosing a trail that angled south. A few steps into the swamp he stood straight-legged and peered south. I took that opportunity to drop to my knees. The buck looked north, but failed to fully check the little bend. Unsatisfied, he gazed south again.

With a shake of his head and a soft snort, the spike loped across to the safety of my side of the swamp. It seemed that this deer was bent on continuing south, but experience told me to wait and see. I reached under the four-point blanket with my left hand and pushed back the two layers in preparation to sit. As the young buck had done, I took a long look, then rolled back. “Old Turkey Feathers’” forestock rested on my left knee as I arranged the blanket so it would not interfere with a clean shot. With my back to the swamp, I watched the hillside trails, but the spike never came my way.

A Constant Flow of Movement

As living historians, traditional black powder hunters attempt to re-create the hunts of long ago. The traditional woodsman relies, in part, on the journals of individuals who lived in his or her chosen historical time period to re-create these adventures. When the historian happens upon an intriguing tale, he or she reads that passage, thinks about what it says and then re-reads it, sometimes over and over. By their very nature, most of these old hunting stories are sketchy at best and require long-term cogitations, additional research and experimentation in the wilderness classroom. That is the nature of living history.

The quest for an authentic and meaningful portrayal is endless. Yet, I fear that sometimes the disciplined research and the thirst for documented authenticity overshadow not only the personal skill development side of traditional black powder hunting but also the fun. Since October I have been re-reading and studying John Tanner’s narrative: The Falcon: A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner. The primary purpose of this exercise was to gather a better understanding of Tanner’s clothes and accoutrements. But as I read, I found myself trapped in the narrow tunnel of material culture documentation, and so I thought it best to put Tanner’s journal aside for a couple of weeks.

This brief hiatus refreshed my perspective and helped me step from the confines of my tunnel thinking, at least far enough back to observe a bigger picture. Present in so many of the 18th-century journals and narratives is a somewhat constant flow of movement with respect to the hunter’s methodology, be it called “stalking” or “still-hunting.” And in Tanner’s case, many of his hunting exploits are prefaced with the movement that led to the discovery of his quarry:

“As I was one day going to look at my traps, I found some ducks in a pond…” (Tanner, 60)

“Going one day with Waw-be-be-nais-sa a good distance up the Assinneboin, we found a large herd of probably 200 elk, in a little prairie which was almost surrounded by the river… (Ibid, 65)

“…I reached a place about a mile distant from camp, and in a low swamp I discovered fresh moose signs. I followed up the animal, and killed it…” (Ibid, 81)

A Closer Look at Still-Hunting

Of late, more readers, traditional and modern folks alike, are asking me about still-hunting. I have still-hunted since Frank Hubbell first suggested “stalking the deer,” I was an impressionable teenager at the time. When I’m engaged in a still-hunt I don’t give the step-by-step methodology much thought, but from time to time, I shall attempt to put in writing some of my practices.

I feel compelled to begin with a word of caution. In many locales, moving about in the forest during a firearm deer season is an unsafe practice, and thus should never be attempted. It is the responsibility of each individual to determine and assess what constitutes safe hunting methodology in his or her particular situation. In addition, the amount of hunter orange clothing (sometimes more than is legally required) is of vital importance to a traditional hunter clad in 18th-century linen and leather garb.

If it is deemed a safe practice, still-hunting is an acquired skill that takes time and patience to develop. In the early going, learning to still-hunt is fraught with frustration and marked by more failure than success, but once a basic level of woodland stealth is reached, the rewards are tremendous.

Trash Today’s “Schedule Mentality”

On that December morning, in my chosen year of 1793, I did not walk into the forest and sit in a “people box,” as my wife calls the local deer shanties, in hopes that a whitetail might venture within 70 paces. No, my woodland heroes did not hunt using that methodology; they went in search of their next meal.

John Tanner, Meshach Browning, Jonathan Alder, James Smith and all the rest of my hunter heroes were tenants of the forest, along with the deer, the wild turkey and the lowly song sparrow. Thus, to walk in Tanner’s moccasin prints, the traditional hunter must study the forest’s many tenants and endeavor to join them.

In today’s world, game is aware of the hunter’s presence before the hunter realizes game is present. Moderns are an impatient lot, driven to clock watching, either consciously or subconsciously, by society’s obsession with being “here” or going “there.” But a successful still-hunter knows no schedule; he or she has no fixed time allotted to traverse the glade. And there is no mention of scheduling in the ancients’ journals, save setting a time and place to meet up, either during or after the hunt.

“Late in the evening, Tom [Springer] killed a large buck and by the time we got it skinned and cut up, it was night. Tom wanted to know what we would do. I told him we would have to camp for the night…” (Alder, 125)

So my first piece of advice is to trash the “schedule mentality.” To clarify, I do not mean leave your watch at home, but rather work to achieve a mental attitude that cleanses the mind of time dependence. In Jonathan Alder’s case, after Tom Springer killed the buck, Alder did not say, “Hurry up, Tom, I’ve got to be…” The pair skinned and cut up the deer and camped for the night.

So my first piece of advice is to trash the “schedule mentality.” To clarify, I do not mean leave your watch at home, but rather work to achieve a mental attitude that cleanses the mind of time dependence. In Jonathan Alder’s case, after Tom Springer killed the buck, Alder did not say, “Hurry up, Tom, I’ve got to be…” The pair skinned and cut up the deer and camped for the night.

Now returning to that December still-hunt, the length of a pause or the number of steps taken between pauses was not fixed, and never is. I have no set rhythm to my ramble, but rather, I weigh each moment and the results of each movement as it occurs, just as that first deer, the cautious one, took its time to assess the security of its circumstance. The point of that deer’s care and concern was to detect danger before it escalated into life or death importance; the purpose of my action was to overcome the deer’s natural defenses without being discovered.

On most still-hunts, I try to progress at a slower pace than the deer, and that pace varies based on the cover, weather conditions, time of day and a host of other factors, some location specific, learned by trial and error. My thought is to allow the deer to move into my immediate area, rather than me into its. That is not always the case, especially with bedded whitetails, but on that morning, two deer passed into and through my area, and a third, the spike did likewise.

If I was stand hunting or hidden in a people box, I would never have seen the spike; by choosing to still-hunt, I happened upon the young buck in the same manner Tanner discovered the ducks, the 200 elk or the moose. Experience taught me to drop to my knees, to reduce my upright human shape to a bump, and experience dictated that the best course was to sit a spell and wait on the buck, once he crossed to my side of the swamp. He never came my way, but had I moved, I would have spooked him. And when he didn’t follow the north trails, I did as Tanner had done: “I followed up the animal…”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to “I followed up the animal…”