The hand-hewed stair seemed steeper, the uneven steps higher. Progress proved slow, the staircase being narrow and confining. Trepidation marked each moccasined footfall. A knowing silence fell upon the twenty-five souls, each pondering the fort’s fate, and his or hers, too. In a smattering of minutes, sweating humanity packed the blockhouse’s second floor as the commander gave orders. Only minutes remained before the first volley. It was June 11th, in the Year of our Lord, 1794…

A loud yell sounded the alarm. “To the fort, everyone to the fort,” I heard in the forest, to the southwest of the blockhouse. A younger man walked fast by me. The stranger never looked my way nor spoke. An abandoned evening meal simmered in a brass kettle in front of a grayed wedge tent, pitched beside the fort. Woodsmen, mostly carrying rifles, bumped shoulders as they entered the south door, then turned right to the stair. I held back, choosing to enter last.

A settler wearing a dirty frock removed the slab doors from the portals. Bright light streamed in. “Commence loading,” Captain Roberts said in a clear, yet stern voice.

A settler wearing a dirty frock removed the slab doors from the portals. Bright light streamed in. “Commence loading,” Captain Roberts said in a clear, yet stern voice.

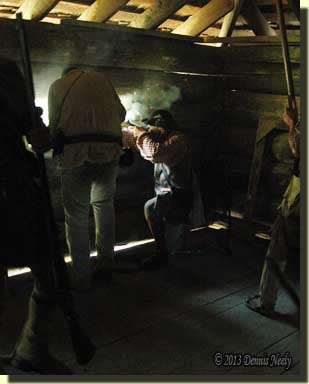

Steady fingers measured gunpowder. Wiping rods thumped patched balls to a half-dozen breeches. Moccasins shuffled as two volunteers shoved their rifle’s muzzle through the break cut in the fourth log from the floor. Each knelt, then primed. The younger man crossed himself, then took careful aim and waited on the Captain. “FIRE!” Captain Roberts yelled.

The two rifles roared at the same instant. Thick white smoke trailed from the muzzles as the pair scrambled to their feet, making way for the next two defenders. Again, two different woodland warriors poked their rifles through the cut in the logs, knelt, primed and peered over the sights. The right rifleman fired first, then the left.

The sulfurous stench of spent gunpowder filled the cramped, second-floor room as the fort’s defenders alternated at the gun ports. The afternoon’s sweltering heat pressed down through the cedar roof shingles, adding to the day’s stifling humidity. Shaky fingers grasped brass and horn powder measures, often spilling a portion of a lethal charge before it reached the safety of a warming barrel. Patch knives slipped, leaving ragged edges. Once in a while a death sphere thudded on the plank floor, then rolled to rest in an open crack with an eerie foreboding.

“I heard it hit,” a greasy hunter said to a well-dressed merchant trying to get to his feet. “You did?” the gentleman asked, straightening his linen waistcoat. Those two brushed shoulders as they passed, which was all too common. In succession, each pan flash illuminated the darkened cavern, lingering as a momentary white patch floating before my eyes. Then all too soon Captain Roberts yelled “Cease Fire!”

In Defense of Fort Greeneville

The Battle of Fallen Timbers in August of 1794 marked the end of the “Indian Wars” that plagued the frontier settlements for five decades. On August 3, 1795, General Anthony Wayne, along with the prominent Native American chiefs of the Ohio country, signed the Treaty of Greeneville at Fort Greeneville in northwest Ohio.

Reading through the journal accounts of that era, which happens to fall in the middle of my chosen time period, it becomes obvious that the dangers and violence associated with daily life in the Old Northwest Territory led to a healthy caution among backcountry woodsmen. The problem traditional black powder hunters face is how to re-create the feelings and emotions evoked by everyday hostilities, and more to the point, how to incorporate those conditioned responses into the fabric of a traditional hunting scenario.

In the late 1990s, Ricky Roberts and several of his fellow living historians discussed this problem, wondering what it must have been like to defend a frontier fort against a hostile attack. Others got involved in the discussion, and in June of 1999, Ricky Roberts’ wonderings evolved into the “Fort Greeneville Match” at the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s Max Vickery Primitive Range, located on the association’s home grounds in Friendship, Indiana.

This unique shooting match honors all participants in the conflict: General Wayne and his men, the chiefs and warriors of the Miami Confederacy and the backwoods settlers of the Old Northwest Territory. The setting is the fort at Greene Ville prior to the signing of the treaty, and the premise is the fort is under attack. Folks close by the two story blockhouse on the Max Vickery Primitive Range are urged to “fort up” and mount a common defense. Fortunately, the attackers don’t return fire.

To maintain the historical integrity of the time period, the match is for flintlocks only—rifles, smoothbores and military muskets. Everyone must dress in period clothing, and to make the competition fair, each participant draws a playing card to match up in three-person teams. Two teams shoot in each relay, one team to the left gun port and one to the right. The targets vary each spring; this year eight-inch steel clangors hung at about 90 yards.

To maintain the historical integrity of the time period, the match is for flintlocks only—rifles, smoothbores and military muskets. Everyone must dress in period clothing, and to make the competition fair, each participant draws a playing card to match up in three-person teams. Two teams shoot in each relay, one team to the left gun port and one to the right. The targets vary each spring; this year eight-inch steel clangors hung at about 90 yards.

Team members start with their guns loaded and unprimed. Shooters load and fire as many times as they can during a set time (this year it was five minutes), priming only when the muzzle is through the window and pointed safely downrange. A certified range officer keeps the stop watch and oversees both teams.

The “Blockhouse Classroom”

I first competed in this event in June of 2003. Much to my surprise, I came away with a tremendous sense of kinship to the other members of my team and to several of the characters who wander through the history of the Old Northwest Territory.

For example, about a month ago I was studying Jonathan Alder’s narrative. At one point, Alder wrote about a skirmish with General Wayne, told from the Native American perspective. Within the passage is this vignette:

“An Indian that stood behind a tree close by asked me why I didn’t shoot; he was loading and shooting as fast as he could. I told him I didn’t see anything to shoot at. ‘Shoot those holes in the fort,’ he said, ‘you might kill a man.’ I told him I didn’t want to shoot. ‘Well then’ said he, ‘you had better get out of here. The first thing you know you will be shot.’ Said he, ‘Didn’t you see the bark fly a little above your head there a little bit ago?’” (Alder, 110)

This passage got me thinking about the Fort Greeneville Match. For a number of years, the complexion of this match has been more about learning and less about winning. I have been a part of a winning team before, but I now look at that match as an extension of my wilderness classroom—the “blockhouse classroom” if you will—a setting that offers a traditional hunter the opportunity to experience a few fleeting minutes of frontier life first hand.

When I read “…loading and shooting as fast as he could,” I vowed to concentrate on the loading of “Old Turkey Feathers.” In the last year, I have discussed the traditional loading process of a Northwest trade gun with a number of knowledgeable living historians. Opinions vary, as one might expect, but prior to the match, I chose to test one theory in particular. The results were mixed and need further testing and refinement before I go into detail.

But in the midst of my test, I discovered two limiting factors that I never considered. The first is the amount of round balls a person carries and the second was the interdependence upon other combatants.

When Ricky called for a cease fire, I had to dump my eighth shot into the bank. There is no question I could have loaded and fired more often during the match, but that was dependent on the rhythm that was established between myself and my partners. It became clear that attempting to step ahead would upset the other fellows’ loading processes and the team’s efficiency. This concern, in turn, highlighted the need for a consistent level of accuracy, in essence the importance of making each shot count.

Along those same lines, I started questioning how many round balls were carried. I had 22 in my pouch, and at my established rate of fire, I came with enough to last for just under fifteen minutes. I immediately started thinking about the purchase of thirty round balls for a prime beaver pelt, but the additional eight balls only adds another five minutes of fire power. So the question is, “How many rounds did they consider enough?”

I understand that the British documented how many balls were issued to each soldier, and I think there is some guidance in those numbers. But I also believe a forted situation is different, to say nothing of casting rifle balls during a prolonged siege. And as Alder’s narrative suggests, which side your persona is on makes a difference, too. At the very least, these issues deserve more discussion and a heap of pondering.

To be sure, treeing in the forest eliminates the dependence on other shooters vying for the same gun port, but that still doesn’t answer the latter question. Like so many wilderness classroom lessons, I came away with more questions than answers. But by the same token, the “blockhouse classroom” provided another memorable 18th-century experience.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to Forting Up