The Laughery Valley tortures flintlocks. The summer heat and high humidity are mostly to blame. The same conditions that foster a gorgeous array of lush spring vegetation humble the flint and steel ignition of my beloved “Old Turkey Feathers.” Spent gunpowder fouls thicker. Black goo forms in the priming pan before the smoky wisps cease flowing from the touch hole. The buckskin wrapped around a stout English flint softens, allowing the rock to come free at the most inopportune time. And quite often, when the barrel is heated from successive shots, a traditional woodsman can feel a hint of moisture coating the frizzen’s face.

On August 24, 1781, a small flotilla of Pennsylvania militia from Westmoreland County, under the command of Colonel Archibald Lochry, spied a buffalo on the west bank of the Ohio River, near a large creek mouth. Someone shot the animal and the contingent landed in anticipation of a fine meal. The 104 members of Lochry’s command were traveling down the river as they attempted to catch up to the forces of George Rogers Clark as part of the plan to attack the British forces at Fort Detroit.

On August 24, 1781, a small flotilla of Pennsylvania militia from Westmoreland County, under the command of Colonel Archibald Lochry, spied a buffalo on the west bank of the Ohio River, near a large creek mouth. Someone shot the animal and the contingent landed in anticipation of a fine meal. The 104 members of Lochry’s command were traveling down the river as they attempted to catch up to the forces of George Rogers Clark as part of the plan to attack the British forces at Fort Detroit.

Unbeknownst to the militia, a small band of Native American warriors headed by Chief Joseph Bryant had been following the soldiers’ advance. Lochry’s men beached their vessels and went about preparing the buffalo and setting up camp. Seizing the opportunity, the Indians attacked. Low on ammunition and caught by surprise, the larger American force was overpowered and defeated in a matter of minutes.

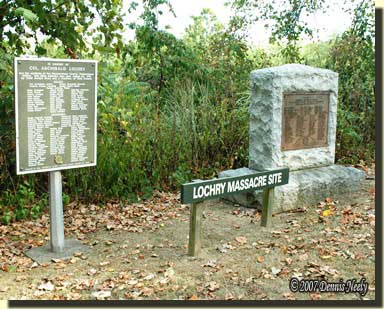

Forty of Lochry’s men were killed in the fight, and he and several others were executed after the battle. The rest were marched off to Fort Detroit as British prisoners of the American War for Independence. In a twist of irony, Colonel Lochry’s name was incorrectly spelled as “Laughery” in the initial government report. The misspelling stuck, and to this day the Laughery Creek flows from Batesville to just south of Aurora, Indiana, passing through the sleepy little town of Friendship, home of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association. Today, a monument in the back of the River View Cemetery commemorates “Lochry’s Massacre” with a listing of all of the soldiers involved.

Pondering Archibald Lochry’s Defeat

I couldn’t help but think of Colonel Lochry and his Pennsylvania militia while I hastily changed the flint in my Northwest trade gun. Out of a hundred-plus flintlocks, I suspect some never fired, some fouled from the humidity, some klatched and yet others might have had flints loosen. There is no way of knowing, but when a Michigan hunter deals with the typical weather conditions of another region, the mind runs rampant, or at least mine does.

I pondered as I stood at the loading bench at Shaw’s Quail Walk, up Caesar Creek, which flows along the east side of the NMLRA’s home grounds. Caesar Creek empties into Laughery Creek, which splits the property, roughly 15 miles west of the Lochry monument. A self-imposed urgency surrounded switching the flint, but nothing like dealing with a surprise attack. I can only speculate, lacking firsthand experience. Hunting is a far cry from combat.

I discovered the loose flint after the trade gun’s lock failed to spark on the first station of the ten-clay match. Like bird hunting, a hammer-fall means a lost bird, and I did not wish to gamble on another lost bird. The flint’s wrap was fine about twenty minutes before, when I took my first fouling shot, but the gun sat while I waited for my relay to start. I noticed the leather felt more pliable than here in Michigan. A new flint rested near the tin that held my .125 cards, “just in case.” The trapper and scorer wanted to wait while I finished, but I told them to go on and that I would catch up. No sense in holding up the other shooters.

The course is set up by bird hunters, for bird hunters. This spring there were four clay birds in the woods and six in the field. The hunter starts with his or her gun capped or primed with the butt off the shoulder, below the armpit. Standing behind a painted stone, the shooter takes a few steps forward, like hunting in cover. The trapper has five seconds to release the clay, just as with a delayed flush.

The first two came from the same electric trap, to the right of the path. The difference between station one and two was the position of the hunter. Both birds rose like flushing quail, following the contour of a steep wooded hillside. The opportunity for a shot was narrow.

The third bird came from behind and to the left, arching high like a grouse winging to safety. A pheasant flushed just to the right and a bit ahead on the path, again flying high and almost straight away. Both birds were hard to see in the foliage and offered a scant few seconds to mount, swing and get off a clean shot.

Most of the morning competitors used double percussion shotguns, about half originals and half modern reproductions. As a courtesy, those of us shooting single barreled guns were allowed to move to the head of the line at stations 1, 3, 5 and 7 so we could get our first shot off and then reload while the double gunners shot. That saved time and moved the group along at a steady clip. Usually the course is laid out so two shots are taken from the same general area, again, saving time.

At the first station in the field, a fast mallard crossed right to left in front of the shooter, maybe 20 yards out. Quite a few hunters shook their head, because they shot just as the bird disappeared in the trees. The next bird reminded me of a Sichuan pheasant, hugging the cover low and flying hard as it angled right to left.

Next, a rabbit bounded along the edge of the tree line, left to right. In the afternoon, Fred Alford stepped into the shooting cage as about seven shooters stood in line, waiting their turn. After capping his percussion double, someone started singing/chanting “Kill the wabbit, Kill the wabbit,” from one of the old Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd cartoons. After the second “Kill the wabbit,” the whole line started singing, and by the third go round, many of the spectators had joined in. The distraction didn’t bother Fred. He called “Pull!” The right barrel boomed. The clay disc broke apart.

A wood duck arched high from the left and then a battue simulated a woodcock, or so I imagined. The last bird was the Sichuan pheasant, low and fast-flying, but presented as a close-by flush. Being low, that bird dropped quick; like so many folks, I missed what should be an easy hit.

But that is the fun of any quail walk. The birds are simple hunting presentations, which are the hardest to hit. The best score posted for the trade gun match was 8-5-3 (total hits, best string of hits, second best string of hits) and second was 4-3-1. By the end of the week, it will take a “9” or “10” to medal in the trade gun match. Sometimes a shoot-off is needed to settle multiple perfect scores—the competition is that tough.

I’ve been away from competitive shooting for about four years. I have come to prefer slipping away to my 18th-century Eden, instead. But I miss the shooting, and I miss the quail walk. Come September, I hope to spend more than one morning chasing the clays up north of Laughery Creek.

Give clay bird shooting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

4 Responses to North of Laughery Creek