Lavender clouds reflected off still water. At the small puddle’s far edge, the image of four poplar trees rooted in tawny canary grass mirrored wilderness reality. Beyond, a young deer slipped through the maple saplings, paused at the wild apple tree, then wandered off into the thicket.

Close up, a dew drop raced down a bent sedge grass blade, hesitated at the dried and shriveled point, then fell, leaving another wet spot on my buckskin leggin. I moved my forearm so the folds of my canvas frock covered the Northwest gun’s lock; my hips scooched to the right on my blanket roll to ease the tingling sensation in my thigh. I grew impatient. I don’t recall what year it was, only traveling back to yesteryear.

A wedge of four mallards winged west, crossing over the watering hole on Shorty’s homestead. Not long after, a red-tailed hawk flapped from a tall hickory at the edge of Shorty’s woodlot. It glided over the thicket with the browsing deer, then swooped up into a stately oak that stood alone on the hilltop. Not one crow cawed or chased the raptor.

On that mid-October morn, the warm, moist air smelled plain and ordinary, certainly not fall-like. Sparrows flitted about, along with an occasional red-winged blackbird and a robin or two, but all remained silent. The usual east to west flights of puddle ducks never materialized, but I sat still, clinging more to hope than reality.

A deep orange flooded the eastern horizon. Not long after, the sun’s golden yellow peeked over the tree line, forcing a return trip to the 20th century. With the blanket roll slung over my shoulder, my elk moccasins backtracked on the slender doe trail that snaked through the canary and sedge grass, the trail I followed in night’s last breath of darkness.

The retreat from my lair was more of a hunched over still-hunt, rather than an outright walk to high ground and the wagon trail that led home. Over the years, a late-from-the-roost duck or two met the death bees along that trail, and despite the lack of ducks a shred of hope still existed.

The retreat from my lair was more of a hunched over still-hunt, rather than an outright walk to high ground and the wagon trail that led home. Over the years, a late-from-the-roost duck or two met the death bees along that trail, and despite the lack of ducks a shred of hope still existed.

Past the fallen oak, around the old box elder, I stopped and gazed east. I did not want to leave so I lingered a few minutes. Then a black dot darted side-to-side as if navigating the tall cottonwoods that ringed the modest pond on the neighbor’s farm. I dropped to both knees and pulled a clump of golden grass over my head and shoulders. The dot veered south, then turned to follow the thin swampy ribbon that led to my puddle. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” I whispered.

A Conversion to Bismuth No-Tox shot

Thirty some years ago, the versatility of a smooth-bored barrel tipped the scales when I weighed purchasing a rifle or a smoothbore kit. A Virginia fowler, Brown Bess, fusil de chasse and the Northwest gun were all in the running. After doing some research, checking local histories and purchasing a copy of The Northwest Gun by Charles E. Hanson Jr., I decided on a Northwest trade gun.

Like so many newcomers to traditional black powder hunting, my first priority was deer hunting. The learning curve for round balls proved a bit steep, until Pa Keeler helped me out. But I was a bird hunter, too, and once I had a grip on spitting out death spheres, I turned my attention to chasing small game, including waterfowl.

That was before non-toxic shot requirements, so I gained a quick education on proper loads of lead shot for everything from Canada geese to woodcock. In October, I especially loved hunting ducks each morning before work. Minutes were limited, but if I hurried back to the house, I could still make it to work with time to spare.

A large cattail swamp a mile or so to the east offered protection for the birds’ night roost. Just after first light, small wedges started appearing over the eastern tree line as mallards, wood ducks and a few teal winged west to spend the morning loafing and feeding on the big mill pond in town or the lakes beyond. Some would drop in to the string of puddles for a quick snack, and now and then, a bird landed on our dinner table.

The first year or two of the lead ban, muzzleloaders were exempted from the non-toxic shot rules. When inclusion came, there was no substitute for lead available that was suitable for the softer barrels of a front-loading smoothbore. I had no choice but give up waterfowl hunting.

Then one day I was talking with a fellow black powder bird hunter. He told me Bismuth No-Tox Shot had just been approved; he knew this because he tested the shot in his flint double guns for the Bismuth Shot Company. He gave me about a pound to try, and that fall found me pursuing waterfowl again. That last-minute wood duck succumbed to one of my first shots using Bismuth.

More than Chasing Whitetails

One side effect of Michigan’s muzzleloading deer season and dedicated black powder seasons across the country is the common misconception that muzzleloaders are “only for deer hunting.” The overwhelming emphasis on in-lines, high-powered scopes and long-range accuracy fuel this misunderstanding. We hear the “only for deer hunting” comment a lot at the outdoor shows and it offers us a chance to flip open the photo albums and show a variety of game taken with our beloved smoothbores.

The historical record bears out the versatility of the cylinder-bored tube. For example, in 1804 John Sayer engaged a native hunter by the name of Outarde to supply his trading post. Sayer’s brief journal entries include a number of instances where either Outarde or some of the other Native hunters supplied waterfowl to the trader:

“…my Hunter brot: the Meat of 2 Deers & 60 fine fat ducks.” (Birk, 37)

“…my Hunter & Pierro gave me 30 large Ducks.” (Ibid)

“…my Hunter brot 30 Ducks, 3 Geese. Pierro 18 Ducks…” (Ibid, 38)

The journals of other hunter heroes include passages that describe taking wild turkeys, rabbits, squirrels, raccoon, porcupine and a host of other small game, to say nothing of cranes, swans and a few other species that are no longer hunted, at least not in Michigan or the neighboring states.

But the proof lies in the doing, and that is the essence of traditional black powder hunting. If a traditional hunter thinks only in terms of deer hunting, he or she misses a tremendous opportunity to form a bond with the hunter heroes of old. Thinking beyond whitetails opens new avenues for re-living history in the wild, to say nothing of expanding the joyous exhilaration that accompanies any trip back in time.

The approaching wood duck held close to the center of the swamp. About 40 paces out, the colorful drake shied away from the puddle I sat beside that morning. If its course held true, I reckoned the duck would pass over my concealment. The sharp English flint clicked to attention. “Old Turkey Feathers’” muzzle inched skyward.

The Northwest gun’s flat, brass butt plate slammed into my shoulder as I rose up. The turtle sight clawed through the streaking fowl, through its green head and through its beak. The hammer lunged. Sparks flew.

The Northwest gun’s flat, brass butt plate slammed into my shoulder as I rose up. The turtle sight clawed through the streaking fowl, through its green head and through its beak. The hammer lunged. Sparks flew.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

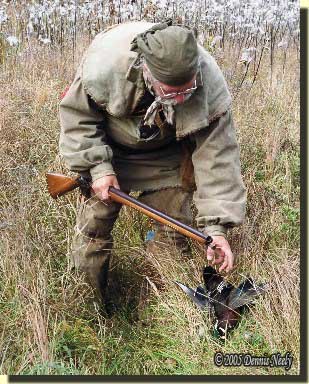

The trade gun’s muzzle raced on, leaving the rolling cloud of white smoke behind. The buttstock dropped from my shoulder. The wood duck cartwheeled earthward, then bounced twice in the short grass that grew on the high ground. That October morn ended differently than expected with a hallowed prize.

Try pursuing other game, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to A Hallowed Prize