Well, I did what I said I wasn’t going to do; I killed a few more paper coyotes. For me, a big part of the fun, and sometimes aggravating frustration, of traditional black powder hunting is thinking through a problem and then testing a hypothesis in the field. As so often happens, a set of results raises more questions, and if time permits, it is back to the glade for more wilderness classroom lessons.

The whole point of the “buck and ball lessons” was to see if the buckshot would kill a coyote if the round ball missed. Opportunities are few and far between, so every shot must count. Our purpose is not sport, but rather game management; I’m getting tired of finding piles of turkey feathers and dead fawn skins.

To complicate matters, when a coyote comes to the call it has to be dispatched; if it is missed or detects the hunter’s presence it is not likely to come to that call again. But with the growing popularity of varmint hunting, more hunters are trying to call in these wary animals. Unfortunately, like turkey hunting, calling mistakes or missed shots only serve to educate the coyotes.

So, rather than cut and paste answers to a number of emails the ball and buck postings have generated, I thought an additional post was in order.

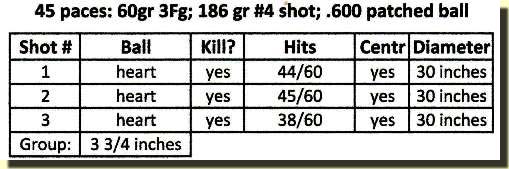

This target tested the “centering” of the death sphere in a birdshot load as described in the third test of this session.

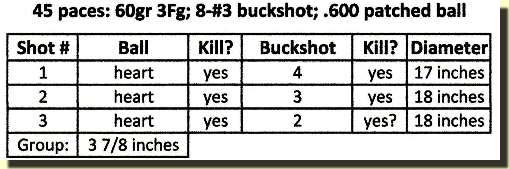

Because the 45 pace (about 42 yards by my pace) results showed improvement with the patched “balanced load” (12-#3 buckshot under a patched .575 round ball) I felt I should try one more time. For these tests, I concentrated on improving the performance of the 45-pace loads.

The first two tests used a bare .610 round ball over eight #3 buckshot, but a patched .610 death sphere is a snug fit even in a wiped, “one-shot-dirty” bore. I started out not wiping between shots, because I was after a period-correct loading method using dry leaves for wadding. To maintain consistency, I continued this practice for the other targets.

But I did not want to deal with a stuck ball, so I broke a cardinal rule of range testing: “Only change one load component at a time.” I made two changes for the next test: I dropped back to a .600 round ball, which weighs 327 grains, and I added a lubed patch. The first change reduced the total load weight from 531 grains to 513 grains, or about 3.3 percent. The second change was made to get a tighter projectile/bore fit in hopes of improving accuracy.

As an aside, one email asked: “…did it hit your point of aim?” On the first 45-pace target (bare .610/8-#3), all three shots were low by 4 to 5 inches. That caught my attention, because I thought the second and third shots at 35-paces impacted a couple inches lower than my point of aim.

Before I started this last set of tests, I fired three shots with just the patched .600 round ball to check the point of impact against the point of aim. I was essentially “right on.” With the buckshot loads at 45-paces, I aimed at the animal’s spine area to compensate. So to answer that question, I am finding a difference: the point of impact is averaging 4 to 5 inches below the point of aim.

The patched .600 round ball tightened the group from roughly seven inches to four inches, registering three “kills.” The first test produced only one questionable hit in the chest area. Plus, the shots sounded better with more of a “bang” than a “thunk.” I saw no difference in recoil.

The patched .600 round ball tightened the group from roughly seven inches to four inches, registering three “kills.” The first test produced only one questionable hit in the chest area. Plus, the shots sounded better with more of a “bang” than a “thunk.” I saw no difference in recoil.

The diameter of the buckshot pattern improved over the first test and had more hits, nine as opposed to five, all resulting in potential kills. I did not expect the pattern to change, but it did, and I suspected that was due to increased breech pressure from a tighter fitting ball and the slightly lighter projectile package. I also noticed that the pattern was centered better around each round ball’s impact point.

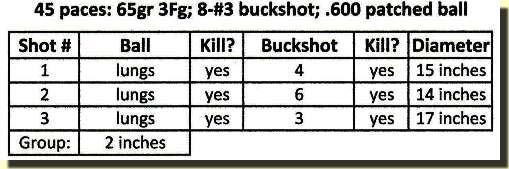

After thinking about the target, I ran another test. This time I upped the powder charge by 5 grains to 65 grains of 3Fg Goex (equivalent to 81 grains of 2Fg). This powder charge is the most I ever use for hunting, and I use much less for target shooting.

The round ball group tightened up to two inches, forming an almost perfect triangle. I noticed the recoil, but it didn’t seem to irritate my neck. This group maintained the three kills produced by the last test.

The round ball group tightened up to two inches, forming an almost perfect triangle. I noticed the recoil, but it didn’t seem to irritate my neck. This group maintained the three kills produced by the last test.

Again, the diameter of the eight buckshot improved; the pattern dropped from an average of 17.6 inches to 15.3 inches. The buckshot hits went from nine to thirteen, so patching the ball increased the hits by 80 per cent (5 to 9) and upping the powder charge increased the hits another 45 per cent (9 to 13). The round ball was close to the center of these patterns, too.

This is a small sample to draw conclusions from. I would like to evaluate the results from ten shots, before making any solid statements. But the results are heartening, and I feel well worth the extra range time.

From the previous tests, I had concerns about the location of the round ball in the pattern. After thinking through the problem, I decided to substitute an equal weight of #4 birdshot for the eight buckshot (186 grains). Even though the two targets showed significant improvement with respect to this issue, I went ahead with this test.

Without thinking, I compensated for the difference of point of aim versus impact point. The first shot hit square in the chest cavity. I marked each birdshot hit with a slash. For the second shot, I aimed at the first hit and the round ball struck 5 inches low. I circled the birdshot and repeated the test. The final death sphere hit about 3 1/2 inches low. In all three instances, the shot pattern spread in a uniform manner and centered around the round ball.

Without thinking, I compensated for the difference of point of aim versus impact point. The first shot hit square in the chest cavity. I marked each birdshot hit with a slash. For the second shot, I aimed at the first hit and the round ball struck 5 inches low. I circled the birdshot and repeated the test. The final death sphere hit about 3 1/2 inches low. In all three instances, the shot pattern spread in a uniform manner and centered around the round ball.

At the end of this wilderness classroom exercise, I have an acceptable buck and ball load that I believe will stop any coyote within 45 paces. This is a huge accomplishment, given the patterns produced by a cylinder-bored gun when loaded with buckshot only. In addition, I have a greater understanding of using a buck and ball in my Northwest gun.

The goal of the lessons was to create a tighter pattern for hunting, as opposed to a broader pattern for warfare. In the future, I would like to experiment with the round ball loaded first, then the death bees. Along these lines, I think it prudent to also test larger-sized buckshot, like that referred to in some of the old manuscripts.

Yes, I still come away with some unanswered questions, and I would like to perfect a period-correct loading method that matches these latest results. But that will have to wait for another time.

Although depleted some more, the bag of #3 buckshot still holds enough shot to disrupt the lives of several coyotes. Right now, I need to collect some furs so I can venture off to the trading post and secure more ammunition.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

3 Responses to Stacking Up More Coyotes