First light ushered in a volley of musket fire. The muzzle blasts, five in all, echoed up and down the River Raisin. A minute or so later, a second unsettling exchange erupted well to the north—four shots, a pause, then two…then three blasts. On that humble morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1794, a sense of immediate urgency gripped the hardwoods and the bottomlands.

Not long before, at the bend in the trail, loud geese ke-honked off to the west near the river’s lily-pad flats. Night’s last gasp was underway. Buffalo-hide moccasins whispered over the hill, around the next gentle curve and down the slope. The eastern horizon grayed. At the first shot all fell silent as the returned white captive hustled to the shelter of an ancient red oak’s huge trunk. Thirty or so minutes ticked away, ample time to resume a humble prayer with Gzhe-mi-ni-doo, the Great Creator.

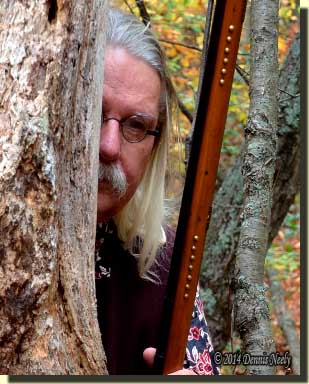

With care and caution the still-hunt continued. The tips of two ears flicked. A butterfly-breath of cool air swayed a tall, yellowing blade of grass. The deer was cross wind. Its ears twitched east, then west. The antlerless head disappeared, then reappeared a few steps to the west as the woodsman stood behind a shag bark hickory and simply watched.

The faint sound of rustling leaves accompanied the deer’s body as it stepped into view. It pawed beneath a stout red oak, itched behind its left ear with its hind hoof and nipped fish-shaped greenery from an autumn olive bush. In due time it wandered off into the little valley and then up and over the rise. “Mii-gwech Gzhe-mi-ni-doo,” the woodsman whispered, acknowledging thanks for the blessing of happening upon the young doe.

The faint sound of rustling leaves accompanied the deer’s body as it stepped into view. It pawed beneath a stout red oak, itched behind its left ear with its hind hoof and nipped fish-shaped greenery from an autumn olive bush. In due time it wandered off into the little valley and then up and over the rise. “Mii-gwech Gzhe-mi-ni-doo,” the woodsman whispered, acknowledging thanks for the blessing of happening upon the young doe.

“Scu-reeeeee…Scu-reeeeee!” A red-tailed hawk cried out as it circled overhead. “Jay! Jay! Jay!” a vigilant blue jay responded. Geese again ke-honked on the Raisin. Perhaps they would go silent or spread a warning if a British patrol or a company of rangers from Fort Detroit materialized on the river’s west bank?

“Kee-honk, yonk, yonk…kee-honk, yonk…” A sizeable wedge of Canada geese winged east to west, but as it flew over the east-bank’s bottoms, the geese veered north and rose higher. Dark, trail-worn moccasins and blue wool leggins edged north, then angled a tad to the east. A large cedar tree, encircled with brush and debris, awaited in a little sequestered hollow. That familiar lair offered a commanding view of the north boundary of the nasty thicket.

Thick, brittle, fluffy leaves littered the forest floor. A chipping sparrow could not approach without causing a formidable ruckus. Fingers dug in the buckskin pouch. A cream-colored wing bone, polished from years of faithful service, emerged. The flat end rested on dry lips. Two tugs of air sent two soft clucks out over the thicket. The wing bone returned to the pouch. The Northwest gun’s muzzle eased to the center of the little valley. An anxious thumb traced lazy circles on the cock’s domed screw…

The Evolution of the ‘Smoothbore Bag’

Last fall I fielded a request for a specific photo to illustrate another outdoor writer’s article on shooting black powder woodswalks. I have an extensive photo library, gathered over the years. Someone suggested he contact me, and I obliged—anything to promote the black powder shooting sports. I don’t know if he submitted my photos, but I had a great time rummaging through the pictures.

At one of the larger winter woodswalks, the club color codes their stations for rifles, pistols and smoothbores in an attempt to match the challenge to the chosen arm. Thus a pistol shooter is not required to shoot a teensy rifle target that is out there 100-plus yards. To some extent, the same applies to the smoothbores.

When I was done with the search, I returned to the photos for the two smoothbore groups I followed that day. I studied each image, paying close attention to the loading methods and bag set ups of the shooters. The more I looked, the more I remember feeling like an outcast.

The interest in smoothbores has grown over the last ten years. In the mid-1980s, when I first ventured to Friendship, Indiana, the home of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association, only a handful of shooters competed with smoothbores. Most of those folks were re-enactors who actually shot round balls and birdshot out of their weekend guns—but only at paper targets, clangors or clay pigeons. Few people hunted with smoothbores, and fewer dressed in traditional attire.

Today almost everyone shoots a smoothbore, which is the reason behind that club color-coding their stations. The forums and social media are filled with newcomers’ requests for information on shooting smoothbores, as are the muzzleloading magazines and video channels. Post a written response, or better yet, a video of how you load your trade gun or what you keep in your “smoothbore bag” and you are an instant celebrity and a renowned expert.

A long-time traditional hunter and I often discuss the current trends we see in the various media outlets, witness at shooting events, or to some degree, view at re-enactments. Of late, the growing size of smoothbore bags, coupled with the expansion of intricacies of loading a smooth-bored muzzleloader (I’m talking more complicated than “powder-patch-ball” in a rifle) take up a greater portion of our conversations. In the end, the comment is always the same: “That won’t work on an actual hunt.”

In essence, a woodswalk or line shoot and a traditional black powder hunt are two different endeavors. Yet, I see more and more living historians carting these smoothbore duffle bags across time’s threshold. At the risk of ruffling some feathers, I feel compelled to ask, “Where is the primary documentation?”

Now, as a traditional black powder hunter, I answer only for the historical me and the items I believe are an appropriate representation of that composite individual. It is my responsibility to research primary documentation to validate those choices. Thus, the majority of my accoutrements are based on existing museum artifacts and/or actual first-person passages taken from the writings of my hunter heroes.

But there are situations where intrusions require a dash of measured compromise, which “stretches” the documentation/truth. For example, I carry a brass powder measure, because of modern safe loading practices. I can find no documentation for such a measure in any of the captive narratives, and it is my opinion that the vast majority of returned captives did not carry a measure in the 1790s.

But there are situations where intrusions require a dash of measured compromise, which “stretches” the documentation/truth. For example, I carry a brass powder measure, because of modern safe loading practices. I can find no documentation for such a measure in any of the captive narratives, and it is my opinion that the vast majority of returned captives did not carry a measure in the 1790s.

With that in mind, I am learning to “palm powder.” Through my experimentation in the wilderness classroom, I am close to being able to measure out a consistent charge of black powder without the aid of a metal, horn or antler measuring device. This method satisfies the safety concerns and approximates what I believe Tanner and others did in real life. I will address this in a more complete post at another time.

Likewise, I have a small deerskin pouch with a bit of tow and two gun worms, which I use to clean “Old Turkey Feathers.” The primary documentation doesn’t seem to support either the little pouch or the tow, but I’m solid with the gun worms. Again, I’m experimenting with using grass and other natural-occurring fibers in place of tow to swab the bore. As I said above, “film at 11…”

The direction of my research is toward reducing the amount of items carried in my deerskin shot pouch, not adding to them. This is why I feel like an outcast; I am moving in the opposite direction of the mainstream and my 7-inch by 7-inch buckskin pouch keeps getting thinner and thinner.

The goal is to experience the simple pursuit of wild game under the same conditions and restrictions as John Tanner, Jonathan Alder and James Smith did. If I can limit myself to what they carried, I can better understand what it was like to live, hunt and survive in the Old Northwest Territory of the Lower Great Lakes.

And here is the big difference from the trends that I am seeing: each change is made after careful testing under actual hunting conditions within an historical simulation that is as close as possible to the wilderness of the 1790s. Thus, as I so often find myself saying, “That won’t work on an actual hunt.”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

4 Responses to “That won’t work on an actual hunt…”