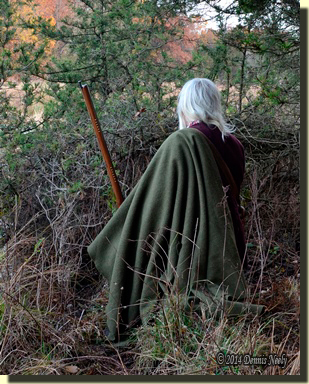

Yellow maple leaves fluttered earthward. Elk moccasins hustled along a churned up doe trail. The hasty stalk skirted a small knoll, then crossed two wagon ruts. Tree-to-tree the hired post hunter wove his way through a half dozen black oaks, but paused at the last red oak before the sedge grass. The moon’s last quarter illuminated the thin fog that veiled the flooded marsh. The air smelled of fall: the acrid aroma of damp, discarded leaves, a hint of wild mint mixed with a twinge of night crawlers.

Seventy paces distant, the dewy branches of a gnarly box elder tree glistened in the hazy moonlight. The tree was rooted on solid ground that eased to the edge of the calf-deep water. The woodsman kept to the doe trail that circled the box elder on the high side, then he turned south, stopping a few trade-gun lengths from the water. That point of land squished a bit, not mucky, oozy or saturated.

Before leaving camp, the backcountry hunter rolled a ripped fragment of canoe tarp and tied it to his bedroll with two buckskin thongs. In the midst of the thick, tangled marsh grasses, he freed the tarp, covered the usual spot, eased his bedroll into the middle and pulled canary grass over his being.

“Wack, wack, wack, wack, wack,” called a hen mallard from a distant pond. An owl hooted its bedtime soliloquy, in the hardwoods, near the great oak where the only colony of grey squirrels in the area lived. “Hoo, Hoo…Hoo, Hooooo…” The hired hunter smirked at the thought that ran through is head, “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you?”

In a humble moment, as the eastern horizon yellowed, Samuel the Trader’s hired man whispered a woodland prayer. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord…”

Waterfowl Season

Each hunting season holds fond memories. Early on in my traditional black powder hunting addiction, the hunting seasons were more defined. Waterfowl season opened before small game, which included pheasants, quail, squirrels and rabbits. I hunted in that order, pausing for white-tailed deer in mid-November. Wild turkeys were a pipe dream back then.

On the south side of the farm, a series of swamps held water by mid-September. The puddle ducks roosted a mile to the east in a large marsh that no one ever hunted. After first light, a hen mallard or two would call, then small flocks took to the air, flying west in search of a wilderness breakfast bar. The string of ponds extended for several miles, so there were many options.

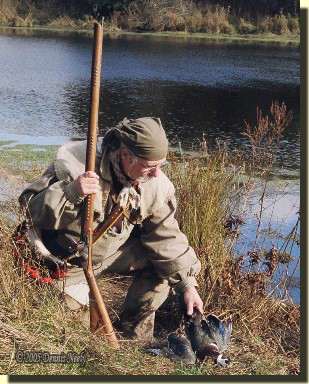

That point, and a few other prime spots, offered a good view of incoming ducks and close-in shots for the cylinder-bored Northwest gun. Although not period-correct, I discovered three or five decoys, spread apart, doubled the chances of taking a duck home. More blocks and the birds winged on to safer waters.

I never set up in the same location twice in seven days, and I skipped days here and there, usually when the refrigerator held a couple ducks. In those early years, lead shot was legal. When the non-toxic rule came to be, muzzle loaders were exempted—for a couple of seasons. I didn’t hunt the first year of non-toxic shot for black powder guns. An alternative to lead did not exist. In essence, “Old Turkey Feathers” was banned from duck and goose hunting. I was angry, as you might expect.

At a muzzle loading sporting clays event, I got to talking with Joe Ehlinger. He shot double flintlock shotguns and loved grouse hunting. He was a champion skeet and trap competitor at the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s national shoots in Friendship, Indiana.

In our conversations, I lamented about not being able to hunt ducks and geese as I always had. Joe smiled, and told me not to worry, he had a solution. At the time, the Bismuth Shot Company asked him to test their contribution to the non-toxic mix in his muzzle loading shotguns. Bismuth shot had just been approved, he said, but too late to make that fall’s waterfowl regulation handbook. He gave me the proper paperwork to carry and a left-over bottle of the bismuth shot the company supplied for his testing.

We talked about my regular lead shot load. Bismuth is about ten percent lighter than lead, so he suggested a modest increase to my shot load component. As I recall, I tested three shots at the pattern board, based on Joe’s recommendation. I saw no difference in the patterning between lead and bismuth.

The next fall I purchased an eight-pound jug of bismuth shot. The price was ten dollars a pound. I still have about four pounds, two-plus decades later. As has always been my practice, when I switch game species, I pull my bismuth loads and save the shot—those odd-shaped pellets might as well be gold-plated, because that’s how I treat them.

I grew up hunting ducks and geese on the River Raisin, too. In recent years, more hunters are “floating” the river, sky-busting and driving off the waterfowl. A couple groups seem to think they own the river. I can’t afford shotgun holes in my canoe, let alone my person. The hassle isn’t worth it.

Waterfowl season opened this morning, but the hired post hunter didn’t go out. Not because he doesn’t want to, he simply has nowhere to waterfowl hunt until the soy beans are cut. The watering hole does not bring ducks in. The standing water in the huckleberry swamp holds wood ducks, but the mucky bottom and quick sand pockets make retrieving a downed bird too dangerous. Geese are my only hope, for now…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.