A Preference for Light-Colored Stoppers

The next phase of the bison horn’s makeover involved fashioning a new stopper. Again, the original violin-peg stopper was fine, but it simply did not suit my needs or preferences. I lost the stopper in my first powder horn somewhere in the thicket east of the south island in the big swamp. Once discovered, I saw no choice but to stop and whittle a new one with the butcher knife. If I recall, I used a finger-sized oak branch about a foot long and didn’t cut the stopper free until after I pared, scraped and fitted it to the horn. That was over thirty years ago.

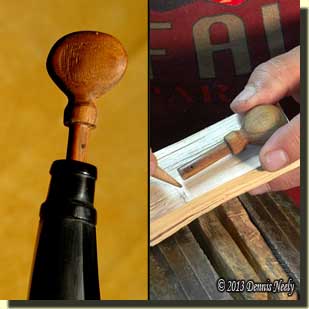

That replacement stopper was a bright, creamy white; the lost one was a bulbous, turned walnut peg that I seemed to always fumble with. As my journey down the traditional hunting path continued, I learned the light colored stopper was easier to see in poor light or when I needed to load fast. It was long and slender with flat sides that offered a sure grip for cold fingers. I’ve made long, flat, light-colored stoppers ever since.

That replacement stopper was a bright, creamy white; the lost one was a bulbous, turned walnut peg that I seemed to always fumble with. As my journey down the traditional hunting path continued, I learned the light colored stopper was easier to see in poor light or when I needed to load fast. It was long and slender with flat sides that offered a sure grip for cold fingers. I’ve made long, flat, light-colored stoppers ever since.

A dry hickory split sat in the corner, close to my workbench. The split’s narrowest edge measured 5/8 inch. I penciled a mark at 3 inches and sawed in 5/8 inch at the pencil line. Once clamped in the vice, a single rap on a sharp chisel split out the straight-grained stopper blank. A pencil dot on each end of the blank marked the future stopper’s approximate center.

Using wood jaw protectors, I clamped about an inch of the blank in the vice so the growth rings ran horizontal and started removing wood with slow, shallow passes of the drawknife. The drawknife’s blade worked the blank’s top flat first, then I flipped the blank and shaved another flat, parallel to the top flat, taking the blank to a thickness of 3/8 inch (the width was still about 5/8 inch).

Using wood jaw protectors, I clamped about an inch of the blank in the vice so the growth rings ran horizontal and started removing wood with slow, shallow passes of the drawknife. The drawknife’s blade worked the blank’s top flat first, then I flipped the blank and shaved another flat, parallel to the top flat, taking the blank to a thickness of 3/8 inch (the width was still about 5/8 inch).

Rough shaping the peg end came next. Dainty cuts with the draw knife soon rounded half the peg. With the blank flipped over, the peg’s rough, round profile took shape with a noticeable taper from the “finger grip” end to the peg’s blunt point. From experience, I stopped well short of “taking too much off.”

Holding the base of a butcher knife’s blade upright with both hands, I began scraping thin hickory ringlets from the peg as I pulled the blade toward me. After three or four passes on each side, I fitted the peg in the hole in the horn’s spout. When about a half-inch of the peg disappeared in the spout, I quit scraping.

Holding the base of a butcher knife’s blade upright with both hands, I began scraping thin hickory ringlets from the peg as I pulled the blade toward me. After three or four passes on each side, I fitted the peg in the hole in the horn’s spout. When about a half-inch of the peg disappeared in the spout, I quit scraping.

To shape the finger grip end of the stopper, I put a cutting of elk hide that I keep on the workbench between the wood jaw protectors and gently clamped the peg end in the vice, taking care not to crush the wood fibers. After a few cuts with the drawknife on each of the grips four sides, I switched to scraping with the upright knife blade.

Alternating between scraping with the knife blade and sanding with a small piece of 120-grit sandpaper, I returned to fitting the peg end to the spout until just shy of an inch of the peg fit snugly in the hole. A thin pencil line marked the progress.

Next I drilled a 1/16-inch pilot hole in the grip and followed that with a 1/8-inch bit, drilling in from both sides so as not to splinter the wood. To allow for shrinkage, I hung the peg on a thin wire over the workbench and set about making the strap.

Next I drilled a 1/16-inch pilot hole in the grip and followed that with a 1/8-inch bit, drilling in from both sides so as not to splinter the wood. To allow for shrinkage, I hung the peg on a thin wire over the workbench and set about making the strap.

About a week later, I checked the fit of the peg to the horn’s spout. There was no change, so I continued sanding until a full inch of the peg fit in the spout. I applied several coats of bear grease to finish the hickory stopper.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.