Reworking the Bison Powder Horn

Bought “sight unseen,” the new bison powder horn was a bit of a disappointment, not that it wasn’t everything the maker said it was. I kept turning the horn over in my hands and thought to myself that most shooters would be proud to own a horn of this quality. I felt a bit ashamed, but at the same time, deep down I had a concern that my alter ego, a returned native captive who can’t give up the humble hunting methods of the Ojibwa, would not possess a horn this nice.

For starters, the bison horn’s butt plug showed a clear contemporary styling: the shoulders flared in a continuation of the horn’s side profile and the plug’s surface was flat. In the evening, I spent some time rummaging through my powder horn books, but I failed to find an 18th-century example close to what I had. As a point of personal preference, the wrought staple ran vertical instead of horizontal.

For starters, the bison horn’s butt plug showed a clear contemporary styling: the shoulders flared in a continuation of the horn’s side profile and the plug’s surface was flat. In the evening, I spent some time rummaging through my powder horn books, but I failed to find an 18th-century example close to what I had. As a point of personal preference, the wrought staple ran vertical instead of horizontal.

I feared the violin-key stopper, fashioned from the same piece of chestnut, might get pulled in the deep swamps and heavy thickets I favored. The fit was tight, but not deep in the horn’s throat. I try to keep my horn tucked under my right arm, but I once lost a similar stopper and had to sit down on the south island and whittle a new one in the midst of a deer hunt.

The neck of the horn sported eight tapered flats that terminated at a small band. I knew I could file the flats round, but then the bison horn would look an awful lot like my old horn, the one that shouted, “I don’t belong to you!” I decided to leave the flats alone.

Of greater concern was the shallow flat intended to attach a strap to the horn; I doubted it would hold a strap firm, not the way I hunt. The thong on the spout of my first horn pulled free; the groove was shallow, too. I did not realize the calamity until the horn slipped from my shoulder, landing spout-down. No powder spilled, but I could have lost it all. I do not wish to repeat that lesson.

Basic Warnings

Before I begin explaining how I remedied each of these perceived maladies, I feel compelled to offer a few warning thoughts. As living historians, it is not unusual to get wrapped up in the excitement of a new project, enough so that one forgets safety precautions, especially when dealing with black powder.

Regardless of who made the powder horn or how they represented it, never use a heat source for any operation that involves a powder horn. Some artisans use a propane torch to burn wood surfaces, then “antique” the surface by steel-wooling the charred wood—never allow a heat source near a powder horn, even a new one of your own manufacture. Likewise, one of the standard methods of loosening epoxy or melting beeswax to seal an imperfection is heat—never around a powder horn. The same holds true for any operation that creates sparks, such as grinding off a staple, etc.—never around a powder horn.

And there is always a possibility that a slip of the file or saw or drawknife will render a prized artifact useless. Thus, I undertake the modification of any accoutrement with the full knowledge that a period-correct repair of a mistake may show forever, or worse yet, that the item might be ruined and the investment lost.

Reshaping the Plug

The urge hit the next evening. I pulled the staple with a screwdriver and pliers, using a small piece of thick cowhide to prevent marring the wormy chestnut. I set the staple on the shelf over the workbench. The chestnut plug was epoxied in place; removing the plug and making a new one was more work than I had time for. Instead, a reshaped domed plug was the sought-after result.

Years ago I made a fixture to aid in filing, shaping and sanding odd-shaped objects. The fixture consists of a stout hardwood dowel glued in one side of a square, eight-inch pine block. I clamped the fixture in the bench vice, then marked the plug’s center with a pencil. The imagined litany of cursing and chastisement from the horn’s original maker stung my ears.

With the horn held in my left hand and resting against the fixture’s standing dowel, I started rasping the sharp edge off the contemporary-style plug. Pushing the coarse teeth toward the center mark with light pressure, I worked the plug in a circle, taking only a little wood with each pass. The horn continued to roll and the circle of finished wood grew smaller in diameter. The rasp cut with a gentle arching motion as the new, period-correct domed shape emerged.

With the horn held in my left hand and resting against the fixture’s standing dowel, I started rasping the sharp edge off the contemporary-style plug. Pushing the coarse teeth toward the center mark with light pressure, I worked the plug in a circle, taking only a little wood with each pass. The horn continued to roll and the circle of finished wood grew smaller in diameter. The rasp cut with a gentle arching motion as the new, period-correct domed shape emerged.

The plug’s sidewall thinned; a pencil marked an eighth-inch margin line above the horn’s edge. In a short while the rasp’s fine teeth finished the rough shaping. Using the rasp as a straight-edge, I checked the dome’s shape. Satisfied, I switched to a fine metal file, then coarse sandpaper.

With the first rough sanding completed, I blew in the spout. Sanding dust flew from the old staple holes, but I expected that. Locust thorns and a light coating of carpenter’s glue remedied that situation. Once the glue dried, I blew in the horn again and found it to be air tight. A damp paper towel raised the grain, followed by another sanding using finer grit paper.

With the first rough sanding completed, I blew in the spout. Sanding dust flew from the old staple holes, but I expected that. Locust thorns and a light coating of carpenter’s glue remedied that situation. Once the glue dried, I blew in the horn again and found it to be air tight. A damp paper towel raised the grain, followed by another sanding using finer grit paper.

On the one hand I envisioned a rough-made horn, but the wedding bands, tapered flats and smooth, shiny surface suggested otherwise. I told myself this horn would someday be sold, so I finished the domed plug in keeping with the nicer workmanship. A holey, gray cotton sock applied a quick coat of stain; I left the wormholes unfilled. When the stain dried I rubbed on a coat of varnish.

I next retrieved the wrought steel staple, positioned it horizontal for the strap and tapped it with a small hammer. Because the wormy chestnut was hard, I drilled two 1/16-inch pilot holes and hammered the staple home. Once finished, the butt plug still looked too new and unused.

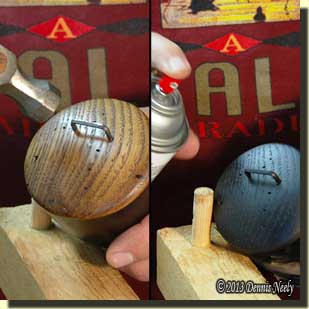

In a fit of disgust, I grabbed an old newspaper, affixed clear packing tape to the folded edge and applied the newspaper skin to protect the horn, making sure the tape masked off the horn but not the plug’s thin edge. A quick spray of flat black paint coated the plug; I again heard the cursing. When the paint was dry, a judicious rubbing with 4/0 steel wool cut to the varnish in spots, leaving an aged, well-used patina.

In a fit of disgust, I grabbed an old newspaper, affixed clear packing tape to the folded edge and applied the newspaper skin to protect the horn, making sure the tape masked off the horn but not the plug’s thin edge. A quick spray of flat black paint coated the plug; I again heard the cursing. When the paint was dry, a judicious rubbing with 4/0 steel wool cut to the varnish in spots, leaving an aged, well-used patina.

I thought about fashioning a better place to secure the strap by stretching wet rawhide, the 18th-century version of duct tape, about the neck and letting it dry; it was obvious the rawhide patch would slip off with continued hard use. With the horn’s neck against the dowel, I cut a groove at the small end of the tapered flats with a round chainsaw file to anchor the powder horn’s strap.

The polished finish on the horn itself also looked too new, plus I expected it would reflect sunlight. In thinking through the project, I had considered scraping the horn lightly with a sharp knife, but the octagon flats at the spout dictated softer distressing, again with resale in mind. Picking up the 4/0 steel wool, I rested the horn on the fixture and rubbed the surface. The polished gloss dulled, enough to satisfy a returned captive. The next step was making a replacement stopper.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.