Lost to Eternity

Layers of damp leaves covered the snag. The ragged knot pressed the wool-blanket liner against the hard callous under my right big toe. An abrupt pause delayed the still-hunt, but the instinctive response came too late. The small hole, the one worn in the buffalo-hide moccasin, the one I thought I could get away with for another hunt or two, tore. To make matters worse, the unseen villain stayed hooked and ripped the thin leather even more when I tried to back off.

Once freed, the morning’s grand stalk veered east. Twenty or so paces downhill, at four red oaks that form the corners of a square, two trade-gun lengths on a side, my moccasins stopped. The right moccasin, gaping hole and all, pushed away the leaves. The wool blanket, rolled and bound with the tails of a cowhide carrying strap, dropped from my shoulder and came to rest on the oak’s downhill side.

A scratchy string of clucks followed by an aggressive mix of putts and squawks emanated from the cedar grove, farther to the east. The altercation continued for longer than normal. Not a cluck or a putt came from my side of the big swamp. Fourteen Canada geese, flying in an uneven wedge, passed over the tree tops. Their big wings swished and swooshed, but they never uttered a sound.

Two deer splish-splashed in the swamp, upwind near the muddy spring, still out of sight. In a few moments, the younger doe stepped into the hardwoods; the mother appeared a couple minutes later. I glanced down. A light blue bead glared back from the bottom of a cupped red oak leaf, to the right of my buckskin leggin garter. I scowled, then went back to watching the two deer plod up the hillside. When they crossed the ridge crest, I again glanced at the lost bead.

Two deer splish-splashed in the swamp, upwind near the muddy spring, still out of sight. In a few moments, the younger doe stepped into the hardwoods; the mother appeared a couple minutes later. I glanced down. A light blue bead glared back from the bottom of a cupped red oak leaf, to the right of my buckskin leggin garter. I scowled, then went back to watching the two deer plod up the hillside. When they crossed the ridge crest, I again glanced at the lost bead.

Not long after, two hushed splashes betrayed another deer’s approach. At the swamp’s edge, shielded just beyond the hill’s last cedar trees, a deer sniffed the tender breeze that caressed the tawny sedge grass. With its head half up, the whitetail looked to the north, then to the south. I thought I glimpsed thin white tines.

I moved my hips to the right, pivoting on the blanket roll. I raised my left knee and rested the Northwest gun on the dark-blue wool leggin. The young buck emerged between the same two cedar trees as the first pair. He sported tall spikes, a good foot long with graceful, matching curves. His well-toned body displayed good health, but he needed another year before becoming a prime candidate for the family dinner table.

The spike turned north, choosing the lower trail that meandered below my lair. As he drew closer, I spied a tiny brow tine at the base of his left spike. Mid-ear on the right, a palm-sized brown leaf was impaled on that spike. I glanced down. The pale blue bead was gone. “Lost to eternity,” I mouthed without making a sound.

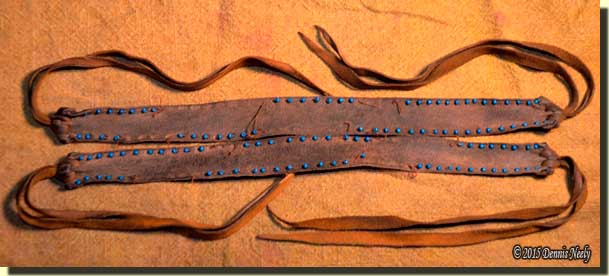

A Trail-Worn Look

That December deer hunt, in the Year of our Lord, 1798, was not the first time I spotted a lost blue bead on the leaves.

My longtime persona, the North West Company post hunter, traversed the forest for 25 years with buckskin strips for leggin garters, cut in haste as a “temporary fix.” After I decided to create a new alter ego, that of a returned native captive who could not give up his Ojibwe teachings, I made a conscious choice to utilize the same buckskin leggins and garters while I researched the proper attire for this woodland friend.

The quest kept returning to a single surviving artifact, a garter preserved by Major Andrew Foster, a British officer whose tour of duty included the Lower Great Lakes in the early 1790s. With the Foster garter as a guide, I made some design decisions and set about fabricating a set of leggin ties that I thought would fit the circumstance of a returned captive. I opted not to use the quillwork panels, but I did copy the single line of pale blue beading on each edge of the garter. I used two-ply, waxed linen thread to secure the 8/0 beads.

As the garters neared completion, I chose not to include the deer hair cones, because I didn’t feel they would hold up to heavy brush hunting. I thought I would see how the garters fared first, reasoning I could always add that adornment later.

In addition, I did not artificially age the finished garters, other than working in a light coat of bear grease with dirty hands. I believe an accoutrement should display honest wear and tear that is a result of actual hunting experiences, but I also recognize that a persona’s material possessions should show a “progression of age and use,” from fresh-made to thread-bare. My lower legs take quite a beating, so acquiring normal wear and tear did not necessitate further aging.

After a couple of winter rabbit hunts, I realized the Foster/Ojibwe style garters did not cut into my legs like the thong leggin ties did—plus they were a lot easier to undo at the end of a day in the woods. Melted snow, rain-soaked sedge grass and then spring mud wet them, allowing the buckskin to take a shape that fit my upper calves.

A week’s worth of life, measured in 18th-century days, brought the first failure: one of the 2-ply linen threads that secured the pale-blue beads broke. I made the discovery sitting cross-legged while scouting wild turkeys. The thread arched out from the garter with the bead hanging off to one side; two other beads were missing. I had a good idea where the garter got snagged that morning; I was bummed.

My research convinced me that securing the beads with linen thread was a viable choice, consistent with the period and locale. I was pretty upset with the misfortune, but soon accepted the break as another learning experience in the wilderness classroom. By the start of small game season in the fall, other threads had broken and the garters lost forty or so beads.

The leggin garters look trail-worn, which is the impression we all seek. The buckskin shows mottled staining and discoloration, yet functions as expected. The disrupted bead lines and straggling threads contribute the most to the overall well-used impression, and that got me wondering how the garters might fare if they had been found among Foster’s trophies. Would a museum curator consider conserving them and eventually displaying them, or would they be assigned a number and entombed in a drawer?

And what about “conserving” them now? In the summer, with two broken threads and maybe fifteen or so beads missing, I considered ripping the bead lines out and redoing them with stouter thread or sinew. What fueled this whim was how “nice” the garters looked when they were new.

But one of the key goals of traditional black powder hunting is to experience “What was it really like…?” This is not an historical beauty contest, but rather an honest search for truth and knowledge that results in a greater understanding of what constitutes authenticity and accuracy. And this failure, if it is a failure, is but another step towards that goal.

A reasonable question is at what point did a hunter hero stop and make a repair? In hindsight, the hole in the buffalo-hide moccasin sole should have been repaired before it tore further, but that was not the only hole in a sole that was so thin it could not withstand pulling a thread tight.

Would a hungry hunter pursuing a family’s next meal stop to sew beads back on a leggin garter that is functioning properly? I think not, I did not; so I will let them age naturally—and learn from what I observe.

Along that same thought line, the deer hair cones on my shot bag and split pouch show no wear whatsoever, much to my surprise. The original idea was to see how the garters worked and maybe add the deer hair cones at a later date. Perhaps now is the right time to add to a fruitful classroom lesson?

And as a parting thought, a few days after that hunt, one of the beads came to rest in a fold in the four-point blanket I had wrapped around my legs. The idea struck me that someone might find a tiny, pale-blue bead ten, twenty, or fifty years from now. What would they think? To what lengths would they go seeking answers? Perhaps the pale-blue beads are not lost to eternity after all…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.