Familiar paths breed complacency. Over the rise, down the slope, then a long pause beside the stagnant water. A blue jay perched on a wild cherry branch. The forest sentinel waited. The hired hunter waited. Now and again, the pungent aroma of rotting flesh mixed with fall’s leafy perfume. A few minutes ticked away, then the blue jay flitted off to the west.

Late-night frost turned to mush before first light. Buffalo-hide moccasins pressed light on damp leaves. Deerskin leggins stepped over the first downed limb. A water droplet clung to the white-crested hook left in the middle of the earthen byway by a wild turkey. Two more heavy limbs, both red oak torn away in different storms, brought the morning course to the little clearing. The River Raisin’s bottomland beckoned, over another rise then down through a stand of dying white ash.

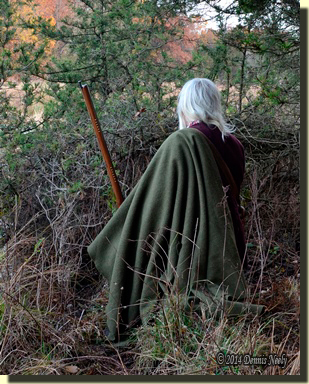

Distant movement caught the woodsman’s eye. The caped, linen shirt’s left shoulder leaned against a white oak that grew on the east edge of Tamara’s Island, a modest plot of ground that rose up in the muck and skunk cabbage. Wet black ooze covered the doe’s legs to the knee as she navigated the bog, upwind, unaware.

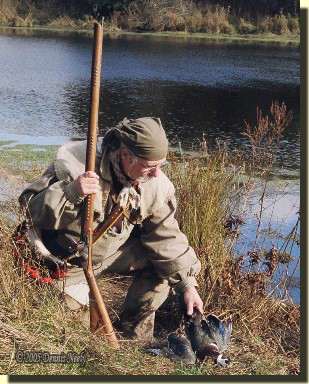

The doe paused behind a barren bush, checked her back trail and looked about. A steady plodding circled the solid ground of the second, nameless island. This deer was young and spindly, offering limited table fare. Besides, she walked beyond the effective distance of “Old Turkey Feathers,” the hired man’s Northwest trade gun.

In due time, the trail-worn moccasins came to the great basswood tree, then eased into the bog. With great care, the hunter stepped upon the moss-covered roots as he also navigated to the dozen or so hardwoods that grew on the island’s high ground. He stalked to the east, danced over the muck, then stopped at a clump of yellow birch trees. He, too, checked his back trail and looked about.

Ten minutes later, the woodsman settled down upon his bedroll, sitting cross-legged on the make-shift cushion with his back resting against the three scraggly birch trees. A fox squirrel lost its grip, high up in a maple sapling, a ways in from the cattails. Its hind end fell. The bushy tail flicked. The branch bobbed. The squirrel regained its footing.

Deer came and went that fine November morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1796. One mature doe showed promise. However, the quest that day focused on one particular buck, a sagacious stag that teased and taunted, but never came close to the backcountry hunter.

An “Ah, Ha!” Moment

During “the camo years,” I relied on a popular skunk-based cover scent. My hunting clothes hung in a trash bag on my side of the garage. When the passion for learning the old ways struck, I shed modern technology with reluctance. Thank heavens I don’t have a lot of photos of those early attempts at living history.

Four-plus decades later, thoughts of those first hunts bring smiles and chuckles, and sometimes a story or two of encouragement for a newcomer to traditional black powder hunting. But one woodland habit remains: I never hunt in the same location more than once in seven days.

Opening day of the firearm deer season in Michigan is akin to a national holiday. The house transforms into “The Murky Swamp Lodge,” or at least it used to before COVID. Out-of-town family came to hunt, sometimes staying for several days.

One guest always sat on the downwind side of a large brush pile which overlooked a modest clearing. As was common practice, we avoided each other’s favorite haunts. I always went “somewhere else,” allowing guests to pick their stand. After all, most plots of ground offer many opportunities, more than most hunters realize.

Well, a couple of days after this family member returned home, I engaged in a still-hunt that crossed a hillside north of the brush pile. This was in the early years of traditional hunting. My alter ego was that of a voyageur plying the River Raisin from Frenchtown to the Grand River portage.

An inner voice instructed me to sit, so I snuggled up under a cedar tree. A doe skirted the east side of the clearing. It kept looking at the brush pile, flicking its ears and sniffing the wind, all the while with tensed muscles, ready to flee. It turned back into the cedar grove and disappeared.

Not long after, another doe approached, this time from the south. She stood for a long time studying the brush pile, then she slipped away. In a matter of an hour, several deer followed the same pattern. They knew a human interloper favored the corner of that brush pile. Needless to say, that “Ah, Ha!” moment did not go unheeded.

I mulled over this discovery. The next noon I drove back to the clearing and walked to the brush pile. I wondered if a hand warmer, glove or some other personal item might be left in the nest. That was not the case, however there were abundant tracks in and around the remodeled lair with the cleared earth, leaving no doubt the deer sniffed the exact spot.

Out of curiosity, I returned to that hillside a few evenings later, a long week after the last time anyone sat at the pile. Deer milled about in the clearing, and only one old doe kept glancing at the brush pile. At that point, I vowed never to sit in the same location within a week to ten days.

Thus, I believe the scent that lingers from a long sitting spell is still detectable into the nighttime hours, and that deer passing by smell the presence, investigate and associate the strong stench with the possibility for danger.

To some degree, sitting on a wool bedroll eases the exposure, but I have no proof or experience of that being true. As a traditional woodsman, I rely on natural scents, such as churning up earth or shaving cedar branches—nothing chemical or heavy scented, such as a hand warmer or morning coffee. I have never seen a deer act as those does did at the brush pile with respect to one of my stands, but again, keep in mind I stay a good hundred paces from a previous stand for a full week.

Further, the scent left from a still-hunt does not linger for long. I have observed deer sniff my back trail thirty minutes after passing with no adverse response. Certainly not like the brush-pile stand drew.

Now some locations hold greater potential than others. That holds true with all properties. Choosing when to take advantage of a given spot sometimes takes a bit of careful planning, and at other times it “just happens.” On that November morn, the latter was the case as I had not hunted off the nameless island in over a year.

Traversing the glade requires a dash of stealth, too. Walking through the center of the clearing is not a good idea. Staying to the shadows works better, taking into account the wind direction and scent travel. A tree-to-tree still-hunt provides optimum protection, which is also period-correct. In addition, deer “move through” a proper still-hunt, just as that doe came into view while the hired hunter paused by the white oak.

Over the years, a humble woodsman learns that some locations are “unapproachable,” that others have “limited access,” and that a few are “scent neutral,” meaning there is almost no “downwind” to that particular place. From Msko-waagosh’s wigwam, or rather the little hollow where it used to stand, the “over the rise, down the slope…” route is the best for approaching a number of areas to the northeast.

Once over the little rise, the steep hills shroud any movement for a fair distance. Crossing the clearing is problematic, but again, choosing the right course minimizes the chance of being seen or scented. The goal is to undertake each stalk as a new, first-time event, steeped with a healthy dose of care and caution, knowing familiar paths breed complacency…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.