A Native Captive’s Powder Horn

The creation of a new persona is littered with pitfalls. When I first decided to re-create the life of a youthful white male captured by Native Americans, raised to adulthood by an adoptive Ojibwa family and who returns to white society but cannot let go of many of the Native ways, I did not fully comprehend the immensity of the project.

To “ease into the persona,” I chose to re-purpose many of the accoutrements from my 1790 post hunter portrayal. Upon reflection, this decision was more right than wrong, but still, not without problems. By October, about a quarter of my material goods were those of a native captive—the rest belonged “to someone else.”

On the one hand, starting before I had assembled a complete outfit allowed me to plunge into this new alter ego with a high level of enthusiasm, and I feel that because I was ill prepared, I gained a broader, although oftentimes frightening, perspective of what was involved in this undertaking. On the other hand, the choice hindered crossing time’s threshold, because I was constantly clothed and accoutered with hand-me-downs, a physical reminder that I was not who I thought I was.

Despite the scarcity of game and an almost empty freezer, I deemed the fall hunting seasons a tremendous success. I believe I learned more in the wilderness classroom than ever before. In many instances, I found myself immersed in the simplest of pursuits to a greater degree than at any time in the past, even when I had to leave the glade because my clothing choices failed to keep me warm.

Despite the scarcity of game and an almost empty freezer, I deemed the fall hunting seasons a tremendous success. I believe I learned more in the wilderness classroom than ever before. In many instances, I found myself immersed in the simplest of pursuits to a greater degree than at any time in the past, even when I had to leave the glade because my clothing choices failed to keep me warm.

Now and again I stopped in the midst of a common action, like loading the Northwest gun, to examine an accoutrement that was not right. I spent the better part of a morning duck hunt cogitating over my powder horn. The one I carried has served me well for over twenty-five years, but on that cool October morn, it did not belong.

What Did John Tanner Use?

The first step in researching an appropriate powder horn for a native captive persona begins with the old journals of the captives themselves. Although I’m not done outlining James Smith’s narrative, it seems he makes no mention of a powder horn. Jonathan Alder speaks of his horn only when he’s caught in a ring fire hunt and the flames are closing in:

“I put my powder horn under my arms and fired off my gun, then leaped…” (Alder, 133)

John Tanner mentions his powder horn three times, but offers no guidance as to its character:

“…I was accoutered with a powder horn, and furnished with shot…” (Tanner, 18); “My powder horn and ball pouch always contained more or less ammunition…” (97): and “…my spunk wood was wet, and I had no means of kindling a fire, until I thought to split open my powder horn…” (207)

Once Tanner split open his horn, I wondered what he would do to replace it, or did he just split the plug? He made no mention of visiting a trading post, or purchasing a new horn. Throughout his narrative, Tanner speaks of killing many buffalo, thus having access to an abundance of bison horns, which turned my thoughts in that direction.

Looking to other sources, I discovered a bison horn in the artifacts Sir John Caldwell took back to England from his 1780’s stint as a British officer in the Lower Great Lakes. Caldwell’s collection is featured in “Bo’jou, Neejee!” (Brasser, No. 140, 142). In addition, a number of paintings by Peter Rindisbacher show bison powder horns, like “A Halfcast with his His Wife and Child,” “Trapping Beaver,” or “Inside a Lodge.”

Making A “Stopgap” Choice

I learned of an already completed bison powder horn, and I knew this horn was only a stopgap choice. My intent was, and is, to build a powder horn from scratch, but time was short, and here was an opportunity to move forward with very little cash invested. I closed my eyes and said “I’ll take it,” sight unseen.

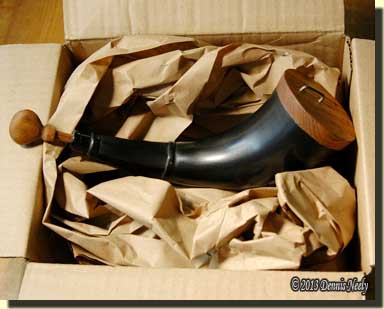

A few days later a cardboard box waited impatiently at my back door. I cut the reinforced tape, pulled the flaps apart and rummaged through the crumpled packing paper like a youngster on Christmas morning. My fingers found the powder horn’s spout and pulled it into plain sight.

A few days later a cardboard box waited impatiently at my back door. I cut the reinforced tape, pulled the flaps apart and rummaged through the crumpled packing paper like a youngster on Christmas morning. My fingers found the powder horn’s spout and pulled it into plain sight.

Disappointment washed over my being and flushed away my excitement. The bison horn was better than expected, more ornate and elegant than a humble returned captive might have owned, or so I reasoned. The maker described the powder horn as simple with a plain, wormy-chestnut butt plug that sported a wrought iron staple. This gentleman understated the horn’s graceful curve and the fine workmanship that included a single wedding band and well-executed flats that tapered to another wedding band near the spout.

As I rolled the horn in my hand, I thought this would make a fine addition to most any shooter’s kit, including some traditional black powder hunters I know. But the horn’s style and embellishment put it a notch above the photo of the Caldwell horn and maybe two notches above those painted by Rindisbacher.

A few days later I took a second look at the bison horn, noting my biggest objections: the contemporary butt plug, the wrought staple’s orientation, the fancy stopper and the horn’s glossy finish. I estimated a couple of hours of hard work might “correct” this horn’s shortcomings.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.