The “Material” of Material Culture

The essence of traditional black powder hunting is the re-creation and study of a hunting lifestyle that existed long ago. To achieve this end, the living historian trades modern outdoor wear for the linen and leather garb our forefathers wore, the common fashion of a chosen bygone era.

But eighteenth-century hunting shirts, leather leggins or tri-corn hats are not usually found on the racks and shelves of today’s sporting goods stores. Fortunately, specialized merchants cater to the needs of the living historian, some offering entire ensembles while others produce specific reproductions of museum quality.

Michigan is blessed with the Kalamazoo Living History Show, the largest juried gathering of living history suppliers and artisans in the Midwest. It is often said that a newcomer can enter this show in street clothes and leave as a period-correct Great Lakes voyageur, a Kentucky long hunter or a backcountry housewife. Around the country, other regional trade fairs meet the needs of the discerning re-enactor in a similar manner.

Michigan is blessed with the Kalamazoo Living History Show, the largest juried gathering of living history suppliers and artisans in the Midwest. It is often said that a newcomer can enter this show in street clothes and leave as a period-correct Great Lakes voyageur, a Kentucky long hunter or a backcountry housewife. Around the country, other regional trade fairs meet the needs of the discerning re-enactor in a similar manner.

Assembling a complete wardrobe can be costly, depending upon the persona chosen. Some traditional hunters opt to make their own clothing, or at least, part of their outfits. This do-it-yourself attitude not only mirrors the self-reliant character of the men and women who forged America, but it also helps the living historian gain a better understanding of what backcountry life demanded of the individual.

Some Thoughts on Working with Fabric

Traditional hunters deal with natural fibre fabrics—linen, cotton and wool—as opposed to the manmade fibers—polyester, nylon or acrylic. Each fabric type offers its own challenges and the peculiarities associated with a given weave or blend must be researched and understood before garment construction can begin.

Here again, the nature of the garment and existing originals guides fabric selection. But it is not uncommon to have a number of fabric types represented in the construction of a given item of clothing. The “who, where and when” of living history—a persona’s life station, geographical location and time period—often comes into play when selecting fabric, and in the case of the traditional hunter, experience in the glade also plays a role.

A fabric’s lengthwise threads are the warp and the crosswise threads are the weft. I try to keep them straight by remembering that a board “warps” along its length. Many times the edge along a fabric’s length is finished so the material doesn’t unravel while on the merchant’s shelf. This finished edge is called the selvage or selvage edge. The selvage can act as a guide when laying out a pattern, but the governing factor is the weave of the fabric.

A fabric’s lengthwise threads are the warp and the crosswise threads are the weft. I try to keep them straight by remembering that a board “warps” along its length. Many times the edge along a fabric’s length is finished so the material doesn’t unravel while on the merchant’s shelf. This finished edge is called the selvage or selvage edge. The selvage can act as a guide when laying out a pattern, but the governing factor is the weave of the fabric.

A fabric’s grain runs lengthwise with the warp threads, and again the lumber analogy applies, because a board’s grain runs with its length. When working wood, the craftsman keeps a watchful eye on a board or plank’s grain, and a fabric’s grain is equally important.

If one takes a piece of linen and folds it so the weft threads run in the same direction as the warp threads, the resulting diagonal fold is called the fabric’s bias. Bias cut fabric stretches and preforms differently than fabric cut on the straight of the grain, thus it is prudent to pay attention to how a sleeve or collar piece is oriented on the linen’s grain. A good way to align pattern pieces is to pull a weft thread, which will create a line perpendicular to the warp threads or the fabric’s grain.

Twisting or turning a pattern piece to “cut better” with less waste often results in a bias cut, and depending upon the piece’s location in the garment, the finished product, say a shirt sleeve, might not hang straight. Another consideration is that most fabrics must be washed, dried and preshrunk before cutting or sewing begins. If this step is overlooked or skipped, the finished garment might shrink and be too small or bind after the first washing.

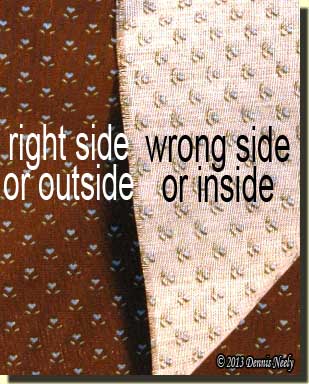

Fabric can also have a right side, or the side seen, and a wrong side, the side against the body. To me, wrong side implies a defect, so when doing a presentation I prefer to say outside and inside. Right side or wrong side is the usual convention listed on patterns or in sewing instructions; I mention outside and inside in case I backslide from accepted sewing lingo.

Fabric can also have a right side, or the side seen, and a wrong side, the side against the body. To me, wrong side implies a defect, so when doing a presentation I prefer to say outside and inside. Right side or wrong side is the usual convention listed on patterns or in sewing instructions; I mention outside and inside in case I backslide from accepted sewing lingo.

Depending upon the maker, a printed cotton calico will have the design on one side only, the right side, which for esthetics is intended to be the outside of the finished garment. Fabric is usually folded and wrapped on the bolt with the right side out, but if there is no obvious difference, the tailor or seamstress should determine which side will be used as the right side and then stick to that standard. And where there is a difference, the right side usually wears better.

Give hand-sewing a try, be safe and may God bless you.