Deer flies swarmed about. A dead cedar branch clawed at a hunt-stained buckskin leggin, then swished the air in its vain attempt to belay an interloper. Silvery dew drops splattered linen sleeves as elk moccasins stalked uphill in that morning’s cool humidity. A red squirrel hopped across the winding doe trail, abandoned for summer travel. A wild turkey hen putted at wayward poults, somewhere close to the ancient red oak where a red-tailed hawk once swooped at a dashing fox squirrel.

That doe trail parallels a deep gulley on the south side. Near the point where the ravine’s crooked fingers join, the earthen path veers around the southernmost wash and emerges from the tight-packed cedars at the meadow’s edge. As I looked up ahead, light spears from a rising sun flooded through the cedar boughs. Even with the jaunt’s slow pace, sweat drizzled down the back of my neck.

There was no definitive purpose for that 1795 ramble in the Old Northwest Territory, other than time travel, but that does not absolve a woodsman from exercising due care and caution. The only objective was a simple circular hunt, perhaps an hour or so in duration. Happenstance eased my course to the meadow, and as the sun’s growing warmth burned through the underbrush, I entertained thoughts of sitting for a spell in the shade of large Rose of Sharon.

There was no definitive purpose for that 1795 ramble in the Old Northwest Territory, other than time travel, but that does not absolve a woodsman from exercising due care and caution. The only objective was a simple circular hunt, perhaps an hour or so in duration. Happenstance eased my course to the meadow, and as the sun’s growing warmth burned through the underbrush, I entertained thoughts of sitting for a spell in the shade of large Rose of Sharon.

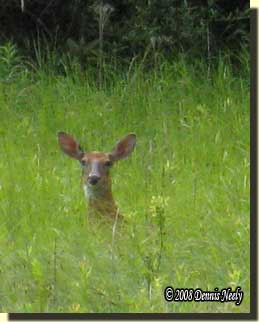

My moccasins paused between the last two bushy cedars that grew beside the wild cherry. The tips of the cedar boughs interlocked, hiding my human form, but they obstructed my view, too. I stood for a while, watching a fine doe’s ears move north behind the hill’s crest. Dew glistened on the prairie grass. Now and again a blue jay swooped from oak to oak in the far tree line.

The doe’s ears disappeared within the thick boughs of the cedar tree to the left, and it was then that I stepped forward to study her progress. The improved view of the meadow also included two turkey vultures standing face to face in a flattened-down patch of green grass, 80 paces distant. One stood higher than the other, and it was that bird that reached down, grasped the unfortunate creature held firm between its gray toes and tugged with its ivory-colored beak. A fawn’s lifeless foreleg rose up, then flopped to the ground as a scrap of flesh pulled free.

I retreated to the shadows and backtracked to the gulley’s first grotesque finger. I hurried down, then up the wash’s bank, across the flat, then down and up again until I arrived at the last cedar before the Rose of Sharon. The far doe must have caught my movement, because she stamped. The one vulture looked at her, then in my direction. I glimpsed the little red rib cage, and my heart sank. Unconcerned with the doe or the two vultures, I struck off with a stern step. The one standing on earth flew first, the other was reluctant, but soon took flight.

A cloud of grief engulfed my being, the antithesis of the elation felt but a few weeks before at the discovery of a new fawn resting beside “Station #3” at the Traditional Muzzleloading Association’s Old Northwest Frolic. From the looks, the fawns were about the same age, no more than a few days old. There was no evidence of a struggle, no sign of a violent end, but even in death the fawn’s frail body did not look healthy.

Without thinking, I knelt and offered a silent prayer. As I asked for God’s care, the back of my fingers stroked the tiny whitetail’s soft, spotted fur. The prayer’s somber tone turned to one of thanksgiving, for in all its harshness, this is the forest reality the woodsmen of November never see. Not far off, the young doe stood in the long shadows cast by the box elders that grow in the point that protrudes from Fred’s woods, causing me to wonder…

Without thinking, I knelt and offered a silent prayer. As I asked for God’s care, the back of my fingers stroked the tiny whitetail’s soft, spotted fur. The prayer’s somber tone turned to one of thanksgiving, for in all its harshness, this is the forest reality the woodsmen of November never see. Not far off, the young doe stood in the long shadows cast by the box elders that grow in the point that protrudes from Fred’s woods, causing me to wonder…

A scarlet cardinal whit-tsued from the Rose of Sharon and another answered, or maybe challenged, from the leafless, gray branches of the broken wild apple tree. At the east tree line, the second vulture limb-walked, half-concealed by the fluttering leaves of the tallest oak; I lost track of the first vulture, but knew it wasn’t far off. Three crows flew up from the blind side of the meadow and perched below the vulture. The doe just watched.

In the glade, finding dead fawns, or deer of all ages, for that matter, is as common as stumbling upon sleeping ones. Each occurrence represents a point in the circle of life, some at the beginning and some at the end. The joy of encountering the fawn at Station #3 stayed with me for days, and the sorrow of discovering the meadow fawn did likewise. Both incidents became pristine moments, mystical points in time when the living historian experiences a deep feeling of kinship and oneness with the hunters of the past, yet each in a different way.

The Haunting Death of a Native American Child

Who knows why, but in the days that followed my thoughts kept returning to Alexander Henry and his description of the death and burial of Native American child. It was sugar making season and Henry briefly touched on the process of boiling down maple sap to make the sugar when tragedy struck:

“…a little child belonging to one of our neighbors fell into a kettle of boiling syrup. It was instantly snatched out, but with little hope of its recovery.” (Armour, Attack, 93)

Alexander Henry tells of the efforts to save the child, but she eventually died. The child’s body was placed on a scaffold to keep the wolves away until it could be transported to the family burial ground.

“On our arrival there…the grave was made of a large size, and the whole of the inside lined with birch bark. On the bark was laid the body of the child, accompanied with an axe, a pair of snowshoes, a small kettle, several pairs of common shoes, its own strings of beads, and—because it was a girl—a carrying belt and a paddle. The kettle was filled with meat.

“All this was again covered with bark; and at about two feet nearer the surface logs were laid across, and these again covered with bark, so that the earth might by no means fall upon the corpse.

“The last act before the burial, performed by the mother crying over the dead body of her child, was that of taking from it a lock of hair for a memorial. While she did this, I endeavored to console her by offering the usual arguments, that the child was happy in being released from the miseries of this present life, and that she should forbear to grieve, because it would be restored to her in another world, happy and everlasting. She answered that she knew it, and that by the lock of hair she should discover her daughter; for she would take it with her. In this she alluded to the day when some pious hand would place in her own grave, along with the carrying-belt and paddle, this little relic, hallowed by maternal tear.” (Ibid, 94)

There is little doubt in my mind that this incident had a profound impact on Alexander Henry’s life, enough so that he wrote about it. The same holds true with the meadow fawn. Such is the way of the forest.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.