Fall slipped away. Three days of intermittent rain and brisk gusts stripped all but the white oaks of their leaves. Overnight the wind subsided, somewhat. An hour after first light, lacy white clouds drifted west, pushed by a chilly northeast breeze. The air smelled empty and cold like it does on an ordinary day in late December.

“Caaww…caaww,” a crow called in a raspy voice, not far distant. “Caaww…caaww,” another answered from the hill that overlooked the river bottom, well to the west. The black demons seemed oblivious to my presence as they hollered back and forth. Neither bird left its perch. Such was that late October morning in 1795, three hills east of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory.

A dozen steps down the hill’s east slope, my elk moccasins struck a familiar deer trail and headed south. Curled leaves covered the earthen ribbon that in most years would be a foot wide, churned up with track upon track, but on that sojourn the path was devoid of any sign of whitetail traffic. Ahead, the sun streaked through the cedar boughs, adding an angelic glow to the barren tree branches. Yet, despite the warming rays, a feeling of desperation lurked in the shadows.

The stalk’s pace slowed just below a small knob’s crest. Over this small hill squirrels often played in the thick understory. I stood for the longest time beside a large red cedar tree, a place I often sit when pursuing deer at midday. The crow sat high atop a dead oak, one of a dozen or so killed by a disease or insect infestation some years back. Nothing was out and about, other than the crow: “…caaww…caaww…caaww…”

The crow finally tired of our game. In a while I worked my way to the bottom of a high-ridged bowl that the sunlight had not yet reached. When a blue jay screamed across the nasty thicket, I again paused, thinking that perhaps I might sit, but I moved on, choosing the lower trail around the thicket.

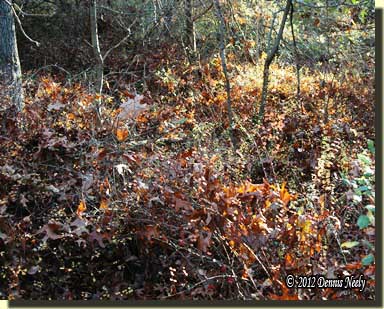

Two dozen footfalls later, I waded through thigh-deep barberries. Brown oak leaves covered the prickly bushes; red, oblong berries festooned the branches. I waded through not because it was easier, but because that is where the trail led. I’m stubborn about that, sometimes. I chose this trail because it was low, hid my advance and afforded a clear view under the outer bushes in the nasty thicket. On the one hand I was looking for squirrels or turkeys in the dry thicket, and on the other, the modern me, tagging along in a distant mindset, was looking for EHD deer carcasses—the reason for the lack of whitetail sign.

Two dozen footfalls later, I waded through thigh-deep barberries. Brown oak leaves covered the prickly bushes; red, oblong berries festooned the branches. I waded through not because it was easier, but because that is where the trail led. I’m stubborn about that, sometimes. I chose this trail because it was low, hid my advance and afforded a clear view under the outer bushes in the nasty thicket. On the one hand I was looking for squirrels or turkeys in the dry thicket, and on the other, the modern me, tagging along in a distant mindset, was looking for EHD deer carcasses—the reason for the lack of whitetail sign.

The sun had not yet found this course, either. In the deep shadow of the high ridge I realized that my nose felt cold and my fingertips tingled. I had not brought mitts, thinking the morning warmer than it was, but I became distracted watching several robins flit about in the bush tops of the nasty thicket. Thoughts of discomfort disappeared.

Circling east, and after passing the monarch oak, I noticed the wind had become strong enough to jostle the sedge grass that grows just south of the isthmus. Now and again a leaf fell, angling earthward with the breeze. At the top of the little rise, at the forked oak where I once shot a fine buck, I sat and waited in vain for a squirrel to emerge or a wild turkey to pass.

A Story of Abundance

Game is scarce this year. During seasons like this I often sit and try to ascertain the reason. It’s not uncommon to recall Mary Browning’s request of Meshach for turkeys for supper:

“About this time, Mary’s eldest sister paid us a visit; and as she arrived at one o’clock in the day, Mary asked me to bring home some young turkeys for supper…Into the glades I went, where I soon saw three or four old turkeys, with perhaps thirty or forty young ones. I sent Watch [Browning’s dog] after them, but they flew into the low white-oak trees; and when I would walk fast, as if I was going past them, they would sit as still as they could, for me to pass on; but after walking twelve or fifteen steps, I would stop and shoot off their heads. I thus kept on till I had shot off the heads of nine young turkeys, and I don’t believe I was more than an hour away from home.” (Browning, 122)

I marvel at the abundance of game and Browning’s marksmanship while “shopping at the local grocery.” On the one hand, Browning’s confidence and matter of fact telling of this tale suggests a common, everyday occurrence, and on the other, I wonder if it was that common, why did he include in his narrative? Yet in the latter case, Browning seems to dispel any thoughts of his feats being out of the ordinary:

I marvel at the abundance of game and Browning’s marksmanship while “shopping at the local grocery.” On the one hand, Browning’s confidence and matter of fact telling of this tale suggests a common, everyday occurrence, and on the other, I wonder if it was that common, why did he include in his narrative? Yet in the latter case, Browning seems to dispel any thoughts of his feats being out of the ordinary:

“I continued till fall hunting bees and shooting turkeys, and as many deer as I wanted. In September old Mrs. McMullen visited us, arriving in the afternoon; and Mary said to me that she wanted some fresh venison, as she knew her mother was very fond of it; whereupon I took my dog and gun, and set out for an evening hunt…” (Ibid, 122-123)

Now, as luck would have it, Browning’s dog, Gunner, jumped a panther from a rocky crevice and the tale takes a shift as Meshach tells the story of besting the beast. He ends the panther hunt by saying:

“This fight postponed my deer hunt, and Mary had to wait the luck of another day…” (Ibid, 124)

Please indulge me as I continue this tale as I cannot in good conscience or fairness to Browning’s prowess fail to report the events that followed. The next morning Browning sets out to fulfill his wife’s request and comes upon “an uncommon big buck.” A stalk ensues that ends in the buck’s demise. I could stop there, but I find the tale’s ending noteworthy and at the same time frustrating, because I no longer possess Meshach’s physical stamina:

“I then skinned him; and taking the saddle, skin, head, and horns, I carried them up a high mountain, and was never more fatigued in my life, than when I got home with my load—the saddle weighing eighty-seven pounds, the head and horns nineteen pounds, and the skin eleven pounds [117 pounds, total]. I believe that was as good a deer as I ever killed in my life, although I have killed larger animals; but he was so fat, and the venison was so tender, that I thought it was fully equal to, if not better, than any I had ever eaten; and Mary and her mother had as much of the best venison as they could wish for.” (Ibid, 124-125)

A Story of Frequent Want

Of late, I have been spending a lot of time studying John Tanner’s narrative. In contrast to Browning’s, Tanner’s life story depicts a constant struggle to survive and subsist.

“We now, as the weather became severe, began to grow poor, Wa-me-gon-a-biew and myself being unable to kill as much game as we wanted. He was seventeen years of age, and I thirteen [about 1793], and game was not plentiful. As the weather became more and more cold, we removed from the trading house and set up our lodge in the woods that we might get wood easier. Here my brother and myself had to exert ourselves to the utmost to avoid starving. We used to hunt two or three days’ distance from home, and often returned with but little meat.” (Tanner, 23)

Tanner’s narrative contains a myriad of stories such as this one, and on many occasions, Tanner or the other hunters return with meat in time to stave off starvation. And in some unfortunate circumstances, the Ojibwa narrowly miss acquiring the food that they needed:

“…I went on with the women to Skut-tah-waw-wo-ne-gun, (the dry carrying place,) where we had appointed to wait for him [Waw-be-be-nais-sa]. We had been here one day when Wa-me-gon-a-biew arrived with a load of meat; but Waw-be-be-nais-sa did not come, though his little children had that day been compelled to eat their moccasins.” (Ibid, 58)

In so many instances, I do not know when the opportunity to time travel will present itself. Often an hour or so simply materializes at the end of a busy day, and when that happens, I try to take advantage of those opportunities. But there are also times set aside for traditional black powder hunting, and whenever possible, I try to limit my food consumption, sometimes fasting, the day before a planned hunt. After following this practice for many years, I believe hunger makes a better hunter.

Tanner’s plight is not uncommon among 18th-century journalists. At some time or other, most fur trade posts dealt with dwindling or non-existent food supplies. Some lamented, as Tanner did, that “…game was not plentiful,” and many times the posts’ hunters were not successful, for whatever reason. But beyond the gathering of wealth through the accumulation of packs of peltry is the realization that both the hunters and the post inhabitants must eat if they hope to see the coming spring.

From the living historian’s perspective, the goal of any traditional black powder hunt is to re-create the circumstances of a chosen historical time period. Over the years, I have come to believe these re-creations should include an honest attempt to duplicate an authentic condition of one’s stomach, as well as one’s clothing, accoutrements or forest surroundings.

A year ago I participated in a traditional hunting camp. On Friday evening, the camp menu included roast venison ribs, and during the meal one of the other traditional hunters expressed concern that I was not eating very much. I responded, “I’m fine.”

A year ago I participated in a traditional hunting camp. On Friday evening, the camp menu included roast venison ribs, and during the meal one of the other traditional hunters expressed concern that I was not eating very much. I responded, “I’m fine.”

A month or so later I got thinking about that conversation and realized I was unconsciously limiting my food intake. In hindsight, I feel bad that I had not shared my reasoning with the other living historians in camp. Not that I was hiding my motivations, rather I simply gave it no thought at the time.

One result of this year’s EHD outbreak is a drastically reduced deer population. In addition, the drought that spawned the midge that carries the infection also seems to have limited the squirrel and rabbit populations, as well. Yet, the aftermath has a silver lining that perhaps only a living historian can recognize: “game is not plentiful.” This unfortunate circumstance prepares the 18th-century stage for what I hope will be a series of true-to-life adventures, complete with incessant growls from a hungry, but period-correct stomach.

And as I study John Tanner’s journal entries, my conviction that hunger is a tremendous motivating force in any traditional hunt is only strengthened. For many woodsmen, hunger and starvation were the way of the forest.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to Returning with but little meat…