Standing corn bordered the swale hole. Tall cottonwoods flourished in the outer edges, amongst the sedge grass and raspberry tangles. The oldest tree, at the swale’s southernmost tip, was dead. Two upper branches tented against the trunk. Slabs of bark littered the great tree’s base. One bark piece dangled in the evening’s cool southwest breeze.

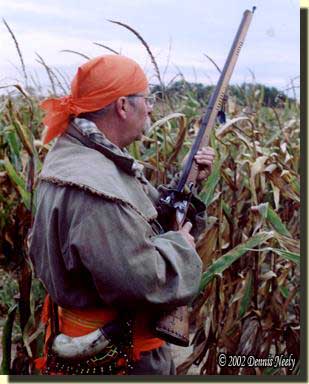

The air smelled sweet and moist. I don’t recall stepping over time’s threshold or passing into a specific year from long ago. This was a late-October pheasant hunt, early on in my traditional hunting. At that time, I don’t remember if I fully understood the mechanics of time travel. I doubt I had a hunt scenario, either. That sojourn’s goal was to experience life in the late 18th century while putting fresh meat on the table.

Two rows from breaking into the open, a cottontail rabbit bounded from a patch of dried grass. The Northwest gun’s hammer clicked to attention. The muzzle swung right, knocking over the tassels of the first row’s short cornstalks. The flat, brass buttplate slammed into my shoulder. My eye found the turtle sight, but the rabbit vanished in a sea of amber grass, and that was that.

Two rows from breaking into the open, a cottontail rabbit bounded from a patch of dried grass. The Northwest gun’s hammer clicked to attention. The muzzle swung right, knocking over the tassels of the first row’s short cornstalks. The flat, brass buttplate slammed into my shoulder. My eye found the turtle sight, but the rabbit vanished in a sea of amber grass, and that was that.

I eased the anxious English flint back to half cock, then stalked the rabbit’s lair. My left elk moccasin pushed away the cover grass. I saw the scratch marks in the dirt where the rabbit’s hind legs pushed off. My mouth felt parched, my tongue sticky, my nose stuffy.

To the east, mixed pasture grasses covered a steep hill that slid into the little swale’s far edge. As I stood between the corn rows, I decided to work the semi-dry swamp from north to south. A dozen footfalls later, I emerged from the corn, walked around a cottonwood and began my usual zigzag dance.

Hunting pheasants or bobwhite quail without a dog is difficult. In my youth, I learned an erratic course mixed with pauses, about-faces and sudden changes in direction unnerved the birds’ confidence and sense of security. I pursued such a course, and in the middle of the swale hole a hen pheasant flushed wild. “Hen!” I shouted in my mind as the sear clicked and the trade gun again settled against my shoulder.

With the smoothbore at full cock, I stood for a long five minutes, or so. With no second flush, I set the hammer at half cock, took an about face, veered left, paused, then turned left again. My elk moccasins took three or four ragged steps. I stopped, and as I did, a second hen exploded from a clump of canary grass. Feathers floated in the air. With the first glimpse of that bird’s head, my body relaxed. I watched as the hen set her wings and coasted into the middle of the cornfield, back to the west.

I chose to wait a bit longer. As I mulled over the location of the two hens, I realized I had not spoken the hunter’s prayer. The western tree line was ablaze with oranges and lavenders as I whispered, “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord.”

“…our birds are all gone, now.”

This past weekend, I had the pleasure of tagging along on the third leg of the Southern Michigan Trade Gun Round Robin, held at the Lansing Muzzle Loading Gun Club in Laingsburg, Michigan. Six clubs each host a leg of the Round Robin. The shooting match is for trade guns only, so the talk of the day, both good-natured kidding and serious historical conversation, centered on smooth-bored trade guns. I was in heaven.

The shoot format is the typical trade gun woodswalk that includes round-ball steel clangors, clay birds, knife and hawk throwing, and fire starting. While competitors waited to try their luck with the clay pigeons, I spoke with a gentleman who said he only hunts deer with his trade gun. When I asked if he hunted birds with his Northwest gun, he expressed interest in turkey hunting, and then, as an afterthought, he said, “I used to like to hunt pheasants, but our birds are all gone, now.”

As the gray-haired shooter stepped to the line for his third bird, I started thinking about what he said in the context of my own frustration over the decline of our local pheasant population. On the drive home, my mind tied together two other similar occurrences with some local history.

The first instance happened in mid-February, at the Deer & Turkey Spectacular, held at The Summit in Lansing, Michigan. Tami and I had our 1790s hunter’s camp set up, complete with several photo albums featuring an array of traditional black powder hunting pictures. On three occasions this year, young people leafed to a photo of a ring-necked pheasant and asked, “What’s that bird?”

The first instance happened in mid-February, at the Deer & Turkey Spectacular, held at The Summit in Lansing, Michigan. Tami and I had our 1790s hunter’s camp set up, complete with several photo albums featuring an array of traditional black powder hunting pictures. On three occasions this year, young people leafed to a photo of a ring-necked pheasant and asked, “What’s that bird?”

The second occurred a few days before the Round Robin. As I started to reread Jonathan Alder’s journal, I came upon a familiar passage, but viewed it in a different way.

In 1782, Jonathan Alder, a lad of six, was captured near his family’s isolated cabin in Wythe County, Virginia. His brother, David, was killed and scalped. With a buffalo tug tied around their waists, Jonathan and another captive, Mrs. Martin, were led northwest toward the Ohio country.

After traveling for seven days, the captors came to the headwaters of the Big Sandy River, built hickory bark canoes and started paddling downstream. At the Ohio River, the Indians crossed to the north bank, chopped holes in the canoes and set them adrift.

“About the second or third day, they killed a large buffalo…” (Alder, 38)

At this point in his narrative, Alder tells how the Ohio Indians dried the buffalo meat. I’ve seen this passage used as a primary “how-to” for jerking meat. But as so often happens with instructive passages, living historians focus on the step-by-step process and read over an interesting tidbit of information: buffalo roamed southern Ohio, between Chillicothe and Huntington, West Virginia, in 1782.

As I drove south from Lansing, my thoughts shifted to the written remembrances of the early settlers in Jackson County, not that far from the headwaters of the River Raisin. In 1837, Mrs. M. W. Clapp wrote of the game seen in the area near Hanover, Michigan:

“The wild deer would gambol over the plains, and the turkey was also seen. Now and then a massasauga put in an appearance, and the wolves and screech-owls would sometimes make night hideous.” (History, 204)

In that same era, W. W. Wolcott told of bears near Tompkins, in northern Jackson County:

“On the way up they crossed a number of fresh bear tracks in the snow; plenty of deer, but got nothing, as their guns were wet.” (Ibid, 206)

Bears, elk, wolves, and for a while, turkeys, disappeared from the River Raisin’s bottomlands, and the historical record offers a reasonable time table for those disappearances. Some settler recollections, penned in the last half of the 19th century, recognize the demise of these species with a nostalgic sense of loss.

Pursuing ring-necked pheasants within a 1790-era historical simulation is not period correct, because pheasants were not introduced in Michigan until March of 1895. The first legal hunting season was in 1925.

If habitat restoration initiatives fail, it is quite possible my son-in-laws and I will be the last to hunt pheasants on the North-Forty. My grandchildren may never have that opportunity. That reality hit home north of Jackson; perhaps the day has come and gone. If that is the case, then like those local settlers, we can only speak or write of fond memories and lament, “I used to like to hunt pheasants, but our birds are all gone, now.”

My course zigged and zagged. Twenty-five paces ate up the remaining cover, save a purple tangle of raspberries to the east of oldest, broken-down cottonwood. I had no intention of wading through the briars, but instead circled them, north to south. A half-dozen steps into the pasture grass to the east of the raspberries, a red-wattle surrounding a panicked yellow eye rose straight up, propelled by frantic wing beats.

“Kort! Okk okk,” the rooster cackled. Cocked and mounted, the Northwest gun’s muzzle chased the ring-necked pheasant’s short tail feathers. The bird’s flight flattened and angled to the west, left to right. The turtle sight passed through the fowl’s body, through the iridescent green head, and when it reached the beak, the hammer fell.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

The rooster’s head pulled back, then went limp. The bird tumbled head over tail, thumping down four rows into the cornstalks. I ran through the smoke cloud at a slow lope, all the while keeping my eye on the pheasant. Before I reached the first row, I returned to a quick walk, whispering a prayer of thanksgiving for a joyous evening and food for the table.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.