“Old Turkey Feathers’” muzzle parted the prairie grass. A circle of white droppings, not more than a day or two old, stared back. Another roost ring, a few steps to the left betrayed the covey’s habit. My thumb eased the frizzen up, then back down. The prime looked good.

With the barrel held high across my chest, I zigzagged to the base of the hill where old box elder trees lay sprawled into the field like fallen soldiers. The grass grew deeper through the tree tops and hid most of the main branches. At each death pile, my left moccasin pressed hard against an upper branch, then rocked up and down, shaking the other limbs. The effort produced no bobwhites.

A warm October breeze slid down the hill and out into the prairie, barely rippling the browning stems. The sweet smell of drying corn filled my nostrils. Now and again a gnarly stick poked the bottom of an elk moccasin, warning me not to step firm. Orange and lavender painted the undersides of fluffy clouds; not much daylight remained.

My heart began pounding as I approached the largest debris pile, formed by three decent-sized trees fallen on top of each other. My thumb fiddled with the hammer screw; the muzzle crept away from my chest and out over the first trunk. Twice an elk moccasin shook a small portion of the tree top, and twice I moved on.

A doe’s bed, matted in the waist-deep grass, caught my eye. Before rocking the next main branch, I investigated the bed. A white dropping lay at the head end. It smeared, lifting my spirits. I forced myself to stand quiet. In a few minutes, I took three or four steps back to the top, determined to gamble the day’s remaining light on the three downed box elders. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” I whispered.

A Love Affair with Quail Walks

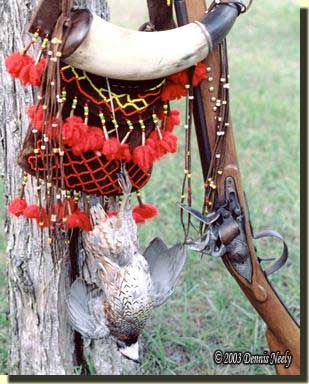

At the 2013 Field & Stream—Outdoor Life Michigan Deer & Turkey Expo in Lansing, one of the guests tapped his finger on a photo of the Northwest gun and a bobwhite quail. He expressed surprise and a hint of doubt at taking a flying quail with a muzzleloading shotgun. He thought muzzleloaders were “only for deer hunting.” Over the course of the weekend, a half dozen other guests shared the same misconception.

At the 2013 Field & Stream—Outdoor Life Michigan Deer & Turkey Expo in Lansing, one of the guests tapped his finger on a photo of the Northwest gun and a bobwhite quail. He expressed surprise and a hint of doubt at taking a flying quail with a muzzleloading shotgun. He thought muzzleloaders were “only for deer hunting.” Over the course of the weekend, a half dozen other guests shared the same misconception.

Taking a flying fowl with any shotgun takes practice. Growing up, I became frustrated with my inability to hit ring-necked pheasants, ducks, geese and quail with the 12-gauge Lefever Nitro Special shotgun. Mr. Myers, my next door neighbor, always responded with “Be patient, it takes a lot of practice.” If there is one attribute a teenager lacks, it is patience.

When I started down the path to yesteryear and completed building Old Turkey Feathers, my focus was on deer hunting, just as the gentleman said. But I was also a bird hunter, and I started scaring birds during small game season. I can still remember the first rooster pheasant that fell to the trade gun’s smoky roar—I jerked the gun when I pulled the trigger, but the resulting lunge provided sufficient lead to drop the bird. I knew it was a lucky mistake, but did that lemon pheasant and wild rice ever taste good!

I ventured to the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s September National Championship Shoot in 1985 as a round ball shooter. There weren’t many matches for “gas pipes,” but I managed to place in the Smoothbore Seneca a year or so later. Over a two or three year period, Roger Rickabaugh kept insisting I should try the Quail Walk, as they had a “trade gun match.”

One morning I walked up Caesar’s Creek to Shaw’s Quail Walk and watched a match. I sat in amazement as the shooters, both guys and gals, broke most of the birds. At the end of the match, the scorer called out “eight” and “nine” a lot. When I heard “ten” (out of a possible ten clays) I couldn’t believe it. I knew I couldn’t hit a one of those birds.

A gentleman dressed in khaki work clothes saw me sitting there and took a seat on the bench, next to me. “Honey, how are you doing today? Ever shoot the quail walk?” the gent asked. The “honey” unnerved me a bit, well a lot. We introduced ourselves, and that’s how I first met Max Vickery. I learned later that was how Max greeted everybody.

Max was a national champion shooter with piles of medals and trophies. He was a past president of the NMLRA, and I read his articles in Muzzle Blasts. From those articles, I knew he was an avid bird hunter. We talked bird and small game hunting and I bared my soul, admitting to the accidental rooster. He laughed and said, “Honey, I’ve done that a lot of times.”

Like Roger, he urged me to shoot the trade gun match, and when I expressed my fear of embarrassing myself, he started to sound like Mr. Myers: “Honey, be patient, it takes a lot of practice.” Of course, Mr. Myers would never call me “Honey.” But then Max said something that has stuck with me for all these years: “You need to shoot a thousand birds.”

He went on to explain that I should set that as a goal, that that was what he meant by practice. He assured me I would be a better wing shooter after those thousand clays, and he said there was no better place to start learning than at Shaw’s Quail Walk.

My wife working on her first hundred birds. Here she misses a mid-sized, passing clay in the woods. “I can’t hit clay pigeons” is her usual response.

The quail walk is a hunter’s match, designed by hunters to simulate actual field conditions. The shooter starts behind a stake. When he or she steps past the stake, the trapper releases the clay—standard, midi or mini—in the next few seconds, just as a bird or rabbit might flush. At Shaw’s Quail Walk, there are usually six birds in the woods and a combination of four birds or rabbits in the open field.

At the time, I doubt if two hundred round balls had left the muzzle of Old Turkey Feathers. Through the winter, I mulled over Max’s advice. In the spring, I bought a Trius trap, sunk a post and anchored the contraption. My goal was to shoot two hundred clays before the June matches at Friendship. I don’t remember if I made it or not. But I went to Friendship determined to meet Max’s thousand bird challenge.

I spent the better part of the week at the quail walk—at least twenty rounds worth—and that kindled my love affair with quail walks. Tony Bowman saw me struggling. He struck up a conversation and offered to shadow me through a round. Max and Tony are both gone now, but I think of them often, especially when I bust a difficult bird.

The NMLRA Spring Shoot is next week, and I’m hoping to make it down to Friendship for a day or two. If I shoot nothing else, I hope to wander up Caesar’s Creek to Shaw’s Quail Walk for a round or two. I haven’t had the opportunity to participate in a quail walk in three or four years. If I can hit five birds I will consider it a success, for now. But come September, after some serious range time, I hope to do better.

I took a deep breath before flexing the next branch with my moccasin. It happened fast, the joyous drumming of twenty or so palm-sized wings. Brown feathery flashes exploded from the grass, flying to the four winds. A black-and-white-headed blur flew to the left, then curved around to my back.

The sear clicked. The buttstock jammed to its rightful place. I twisted around. The turtle sight chased the lightning bolt, then swung through. Sparks showered. The smoothbore thundered.

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

As I picked up the limp quail, I said a short prayer of thanksgiving. Then I chuckled to myself as I imagined Max standing there saying, “Honey, I told you ‘a thousand birds.’”

Give a quail walk a try, be safe and may God bless you.