The brush camp needed work. The humble abode offered shelter for a starry night, but the cedar-bough covering lacked fullness and would never shed even the slightest of showers. The ridge pole and rafters held years of life; the grape vines that lashed the frame together would see the next spring. Weeds grew in the stone fire pit; what little kindling remained sat in a rotted, punky hump.

A blue jay sung a soft melody as my moccasins circled the camp on a calm afternoon in mid-October of 1798. After walking about, I pulled the blanket from my left shoulder, folded it square and dropped it beside the oak that supports the angled ridge pole. The tree’s heavy bark felt warm on my back. Green leaves rustled overhead; the air smelled of distant smoke. A fox squirrel chattered somewhere near the watery edge of the huckleberry swamp.

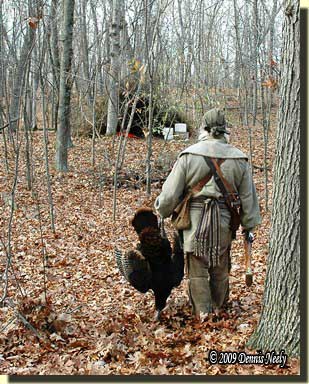

The old camp occupied my daydreams earlier in the day, and I considered reviving it for the fall hunts. Making it habitable again demanded at least an afternoon’s worth of labor, maybe more. My mind drifted to past times, to wild turkeys and white-tailed deer that returned with me to the brush shelter. I recalled the winter the ridge dislodged under the strain of a heavy, wet snow, and reminisced about rabbits, fox squirrels and one fat, fuzzy raccoon.

As I sat, I found myself feeling squeamish, like a stranger who had come upon someone else’s camp. In truth, all of those memories belonged to an 18th-century woodsman who supplied meat for a small North West Company trading house a ways down the River Raisin. The tiny brush camp did not fit, I did not fit. Simply put, that shelter held too many memories.

I scrambled to my feet, adjusted the blanket over my shoulder and struck off to the east. In a short distance, my moccasins crossed the wagon trail, then chose the buck path that leads south. A woodpecker tapped on a dead oak limb at the bottom of the hill. I paused at a low-spreading juniper and took a seat. The hardwoods grew quiet and restful. I clucked once on the wing bone call and waited a spell.

I scrambled to my feet, adjusted the blanket over my shoulder and struck off to the east. In a short distance, my moccasins crossed the wagon trail, then chose the buck path that leads south. A woodpecker tapped on a dead oak limb at the bottom of the hill. I paused at a low-spreading juniper and took a seat. The hardwoods grew quiet and restful. I clucked once on the wing bone call and waited a spell.

In due time I began to still-hunt to a favored location overlooking the isthmus between the two halves of the nasty thicket, a place wild turkeys liked to pass on their way to the evening roost. A fox squirrel barked slow and steady, over the isthmus and up the knoll where I killed a fine buck a few Decembers ago. When I came to the spot, I pulled the blanket around my shoulders and sat hidden behind an oak with a huge broken limb that tented against its trunk.

A few minutes passed, then a turkey clucked soft and abrupt, maybe eighty yards to the south. My thumb pressed hard on the trade gun’s hammer. I turned a bit and squinted, enough to block my eyes from view, but not enough that I couldn’t watch the hillside. More minutes passed, then leaves rustled in the unmistakable rhythm of footfalls.

I came to realize the sounds were to my left, not straight ahead. With great care I eased about. Not forty paces distant, autumn olive leaves moved against the gentle breeze. The leaves bounced along the buck trail with a steady, plodding cadence. At a break between trees, a descent first-year buck, a five-pointer I think, stepped out. A heavy, forked branch from a fresh-rubbed autumn olive bush draped over his shoulders; I saw small twigs entwined in his left beam. The young stag wore his woodland mantle with an air of pride and a hint of arrogance, as if to say, “Don’t challenge me!”

Down the hill, at the isthmus’ mouth, a graceful spike shadowed the 5-pointer’s course. Geese ke-honked off to the east. The spike stood half-behind a good-sized oak, sniffing and watching. A turkey clucked again, but not much closer. Growing clouds dimmed the forest well before the sun set. Now and again, a whiff of wood smoke accented the growing drama. Two soft clucks seemed to answer the first. I turned back and squinted at the hillside, hoping for a chance.

The flap of big wings dashed those hopes. The little spike walked to the north and I don’t know where the five-pointer wandered off to. A whitetail snorted in the distance. Two trees behind me, a fox squirrel started into its end-of-day chatter. Another joined in, and in a few minutes my moccasins began the lonesome trek across time’s threshold.

A Fall Hunting Camp

It is almost impossible to pick up the narrative of an 18th-century hunter hero and not read about some sort of hunting camp or make-shift shelter. In early November of 2009 I spent several afternoons constructing the brush camp, inspired by Meshach Browning’s “bush-camp:”

“There was a little shelter, made of pine bushes…” (Browning, 110)

A heavy snowstorm in February of 2010 flattened the camp; the limb the ridge pole rested on broke from the additional weight. The following fall I rebuilt the camp after choosing a better support and securing the ridge beam with several wraps of stout grapevines.

A heavy snowstorm in February of 2010 flattened the camp; the limb the ridge pole rested on broke from the additional weight. The following fall I rebuilt the camp after choosing a better support and securing the ridge beam with several wraps of stout grapevines.

I have had many different station camps over the years; some used overnight, others for a month or two, and some, like my cedar bush camp have stood the test of several years. Most often, a shelter comes to life based on an old woodsman’s journal that happens to hold my fancy at the time, and that lasts until another author’s words capture the imagination of the historical me.

To be perfectly clear, I do not spend days or weeks on end in these camps, as much as I’d like to. Please keep in mind that sometimes the entire hunt, including camp time, lasts for less than two hours. Modern life just never seems to afford the time for more extensive traditional black powder hunts. That frustrated me for two decades, and as a result, I never seriously considered building a station camp because I knew “I would never use it.”

Then, on a whim, I pitched the wedge tent and left it up for a couple of weeks during duck season. I started each hunt at the camp. I stowed the gear that I didn’t need for the river, but knew I wanted later in the morning. At the end of the morning’s hunt, which a busy work schedule usually limited, I returned to camp to sit a spell before hopping the next time machine back to the future. And after all, the historical hunts I read about either started or ended at camp.

The following fall, a lean-to that incorporated a single canoe tarp sprung up overlooking the huckleberry swamp. Again, I started and ended each hunt at that camp. Now and then I napped in the sun “at the camp,” repaired moccasins or kindled an evening fire for an “in camp supper.” I cleaned and skinned game at that lean-to, and I left it up until the canoe tarp rotted off the frame.

At times I have pitched the wedge tent for a special hunt, or if the weather was good, spread out a trade blanket beside a wind-fallen tree trunk. Last year the Browning-inspired camp saw little use, but this year I was hoping to change that, but the emotions I experienced sitting in that camp surprised me.

On that evening, the cedar bush camp seemed misplaced in the midst of the historical me’s time travels. I’m not sure what my emerging persona will do for fall shelter, perhaps nothing at all for this season. I’m content to let my alter ego make that decision. But that evening I learned a valuable lesson: the old camp holds too many memories…

Add a shelter to your traditional hunts, be safe and may God bless you.