Two hen turkeys clucked, then squabbled. The ruckus came from the south; those birds sounded roosted, an hour after first light. A fox squirrel frolicked at the base of a red oak. Not far away, a blue jay watched from a witch hazel branch. The jay cocked its head as if it was deciding whether or not to scream. A hushed, six-note yelp echoed over the huckleberry swamp. One of the turkeys to the south answered in like fashion.

That October morn, in the year of our Lord, 1795, smelled fresh as it does after a warm spring rain, yet the acidy scent of fallen leaves tingled the nose now and again. The air was cool, but not crisp. A lingering dampness opened the possibility of stealth, a chance to stalk the wild turkeys, but as I sat hidden in the broken down top of an old hickory tree, I whispered, “not quite yet.”

Not fifteen minutes later, the turkeys grew silent, as they sometimes do. The antics of squirrels, chickadees and chipmunks nudged the sun along, as did a passing melee of angry crows and two or three wedges of low-flying geese, winging their way west to the River Raisin.

About mid-morning a single muzzle blast broke the tranquility. The shot came from the far side of the Raisin and echoed up and down the river bottom. Out of habit, my thumb traced an uneasy circle on the ear of the Northwest gun’s hammer. The Raisin’s deep current separated me from the other wilderness tenant, but as the minutes ticked away, that proved of little consequence.

As I sat and contemplated this new development, the complexion of the sojourn changed. The hope of happening upon a wild turkey still existed, but the primary purpose shifted to scouting around the nasty thicket and huckleberry swamp for other British spies.

As I sat and contemplated this new development, the complexion of the sojourn changed. The hope of happening upon a wild turkey still existed, but the primary purpose shifted to scouting around the nasty thicket and huckleberry swamp for other British spies.

With care and caution, I scrambled to my feet, kicked leaves and twigs into the nest I cleared at dawn and struck off to the south on the mid-hill doe trail that skirted the nasty thicket. Not far ahead, a plump gray squirrel appeared from behind a white oak, but I paid little mind. Instead, I concentrated on watching my back trail and surveying from side to side.

In a short while a doe loped in the shadows, ahead and to the left. Two spring fawns followed, browsing as they went. I paused again, checked about, then moved with the does, paralleling their course but keeping my distance. Those deer slipped away, but over the rise and just before the raspberry brambles I glimpsed another young deer at the northeast corner of the thicket, near the stagnant water. Again I paused…

British Spy or Shawnee Scout?

Some days the wild turkeys peck and scratch along the doe trail that eventually passes close to the broken down shagbark hickory. Unfortunately, that October morning I guessed wrong. When an ambush fails to materialize, I tend to hold on to hope longer than most hunters, I suppose because time is always so limited for my 18th-century wanderings. After all, traditional black powder hunting is a pastime.

But the gun blast of a squirrel or turkey hunter in the hardwoods on the other side of the River Raisin provided an opportunity to turn the remaining thirty or so minutes into a productive learning experience, one not entirely set on pursuing wild game. Hearing a gun’s report is not uncommon in the modern environment, the stage upon which our historical simulations must take place. For the traditional black powder hunter, someone else’s muzzle blast can be viewed as an unwanted intrusion or a chance to take a fruitless chase in a different direction.

Growing up, one of my jobs on the farm was checking fences for fallen trees or other damage that would allow the cows to get out. When I started down the traditional path to yesteryear, I still had to check the fences on a regular basis. It was then that I devised the game of “spies and scouts,” weaving a modern task within the fabric of my simple pursuits.

At first, spies and scouts was about covering ground, traveling light and fast. With time, my understanding of re-enacting matured, and the rusted posts and woven wire fence disappeared, at least in the context of my 18th-century adventures. The fencerows evolved into blazed trails, and when I ran out of fence to check, the playing field for spies and scouts expanded to include the trails in and around the various natural features of the North-Forty.

In those early years, squirrels, quail, pheasants and cottontail rabbits were plentiful. In season, I might take small game, if the opportunity presented itself, but I would avoid spooking the white-tailed deer that I happened upon. At some point, I recruited those deer as “bit-players” in my historical hunting scenarios. And when the wild turkeys were re-introduced in southern Michigan, they became bit players, too, “hostiles” in my 1790s Eden.

The objective of spies and scouts is to move about the forest without being detected. When the doe loped into the shadows, she became a British ranger out of Fort Detroit, but when her fawns arrived, the solitary scout grew into a more serious hostile presence. I chose a bold course by following them, but that is how woodland skills are honed.

The objective of spies and scouts is to move about the forest without being detected. When the doe loped into the shadows, she became a British ranger out of Fort Detroit, but when her fawns arrived, the solitary scout grew into a more serious hostile presence. I chose a bold course by following them, but that is how woodland skills are honed.

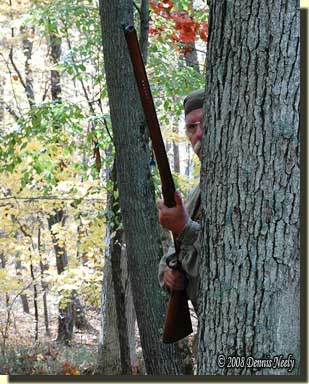

The trio moved faster than I felt comfortable with, so when they wandered over a knoll, I leaned against a tree for a bit to make sure I wasn’t walking into an ambush. If, on the other hand, one or more deer spot me, I sit motionless until it is safe to retreat. If I draw a snort and the deer run off, I consider myself shot and lost to eternity.

In some ways, turkeys are tougher adversaries. If I run upon them in the midst of a round of spies and scouts and the fall turkey season is open, I become the aggressor and willingly engage them, if I have caught them unaware. But if they putt and race off, then I am the one who will be lost to the wilderness.

My best encounters with turkeys, from the standpoint of spies and scouts, seem to occur during deer season. The first priority is always putting fresh venison on the family dinner table, but wild turkeys wandering into a still hunt automatically initiate a brief game. For me, the challenge is to avoid detection, to become a worthy wilderness tenant, and that task is hard, but never without the unexpected.

Quite a few years ago, I think during an early September goose hunt, I played spies and scouts on the way back to camp. A frolicking fawn caught an ill-advised movement. The British agent stood and watched for a bit, alternating glances between the oak that hid me and its dam. When the little button buck walked towards the doe I slipped away and took a seat just down from the ridge crest, concealed by a broad red cedar tree.

At least ten minutes passed. I heard the doe snort, then stomp. She never saw me, and I did not consider myself shot, much less mortally wounded. A few moments later that buck fawn stood beside the oak that once hid me. It sniffed the ground, looked in my direction and started plodding straight at me, nosing out my scent like a hound pup.

Over top of the fawn’s back I saw the doe circling downwind of the oak. She snorted and stomped, trying to warn the youngster, now not more than five paces distant from my fortification. After it got a snoot full, the brash Englishman retreated back to the oak. I have never figured out how to score that encounter, but I refuse to believe I was the one who succumbed.

Give spies and scouts a try, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to “…not quite yet…”