Thirty two Sandhill cranes winged overhead. Each day the groupings grew bigger, and the chortling and gurgling increased. The cranes spent more time in the air and less in the fields, presenting a clear sign winter was not far off. The sky was bland and ordinary that morning, the air calm and chilly, smelling of dry oak leaves. It was late-November, in the Year of our Lord, 1797.

Thirty two Sandhill cranes winged overhead. Each day the groupings grew bigger, and the chortling and gurgling increased. The cranes spent more time in the air and less in the fields, presenting a clear sign winter was not far off. The sky was bland and ordinary that morning, the air calm and chilly, smelling of dry oak leaves. It was late-November, in the Year of our Lord, 1797.

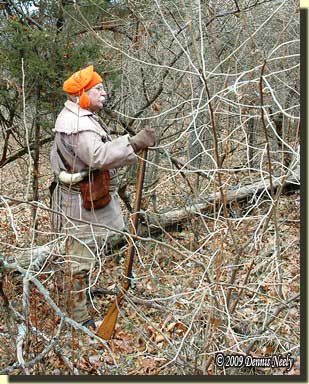

My back rested against the three-trunked maple, where the tall forest trees meet the shorter, thinner saplings of the river bottom. The River Raisin beckoned, as it so often does, but I sat still and fought the urge to get up and wander about in the bottoms. If they came through, the deer would arrive soon. Dawn broke late. Still-hunting could wait.

The deer never ventured into that part of the woods. I sat stone-faced, not moving a muscle. I breathed slow, imagining dozens of whitetails, all with large antlers, wandering along the trail that angled to the west and into the impenetrable cattails, but to no avail. Six blue jays came and went along with several cardinals and a host of flitting sparrows, all silent, all seemingly unaware of my presence. A plump fox squirrel captured my attention for a good long while before I drifted into prayer.

Some days the trials and tribulations of 21st-century life burden a weary time traveler, interrupting any and all attempts to journey back to yesteryear. At other times, the gentle slide into the 1790s becomes an abrupt, unexpected free fall, as if a moccasin lost its footing on a mossy rock, sending its wearer over the precipice.

That particular morning I crossed into 1797 in a peaceful manner and frolicked for a while. I became caught up in the signs of winter. I counted the Sandhill cranes and the blue jays to pass the time. The mental exercise washed away what little remained of the present and secured a magnificent aura of the past. Yes, putting fresh venison in the freezer was the main objective, but, as happens once in a great while, the morning turned into a soul cleansing walk before the Creator.

With little forethought, I got to my feet, slung the bound bedroll over my shoulder and struck off into the Raisin’s bottomland. I never checked the Northwest gun’s prime; it hung at arm’s length like a tag-along afterthought. The prayer continued in the midst of the usual two-steps-and-a-pause still-hunt. At times, the words were whispered and at others they simply passed through as conscious thoughts. An hour or so later, I left my forest Paradise calm and refreshed, at peace with life.

Stumbling Upon a Hidden Story

Last week I had occasion to pull out my file on Madame La Framboise. I was researching the date of her husband Joseph’s death in preparation for an early-summer trip to Mackinac Island.

I first encountered Mme. La Framboise in the cardiac intensive care family waiting room of St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in the fall of 1995 (Johnson, 108). That first introduction resulted in an ongoing discussion that eventually led to awareness of the portage between the River Raisin and the Grand River. From my readings, I believe it is likely Mme. La Framboise and her canoe men journeyed along the River Raisin, passing through the North-Forty in the early 19th-century.

Marguerite-Magdelaine Marcot was born in 1780 to a French-Canadian fur trader, Jean Baptiste Marcot and Marie Neskech, the daughter of Kewinaquot (Returning Cloud), a celebrated Odawa chief. She married Joseph La Framboise, another French-Canadian fur trader about 1795 in the “custom of the country.” The marriage was formalized in July of 1804 by Father Jean Dilhet at St. Anne’s Church on Mackinac Island. The La Framboises’ fur trading business prospered, and Magdelaine became known as “Madame” prior to Joseph’s untimely death in 1806.

Accounts of Joseph’s death vary, but in the fall of 1806 Joseph, Magdelaine, their young son Joseph and their voyageurs began the return trip from Mackinac Island to their fur-trading post on the Grand River near Lowell, Michigan. About a day out of Grand Haven, at an evening campsite near a Potawatomi village, Joseph knelt for his nightly prayers. While praying he was stabbed to death by Nequat, a villager who was upset at Joseph’s refusal to trade liquor. After burying Joseph near Grand Haven, the courageous Mme. La Framboise continued on to the winter trading post and became one of the most successful traders in the Upper Great Lakes region.

My Mme. La Framboise file contains copies of every account I have found on her life. But, when I rummaged through them last week, I noticed a detail that had eluded me: they were devout in praying the “Angelus,” a devotional prayer. Some observers noted that they stopped at the appropriate hour to offer the prayer three times a day.

I knew both Joseph and Magdelaine La Framboise were Roman Catholic, Joseph by birth. About age nine, Magdelaine’s mother, Marie (I find no documentation as to whether she was a convert), allowed her to receive religious instruction from the Jesuit Fathers who were missionaries in the Old Northwest Territory. One account says her religious education included tutelage at a convent in Montreal. As her prominence in the fur trade grew, Mme. La Framboise became a benefactor for St. Anne’s Church on Mackinac Island.

So often when I reread a narrative, or as in this case, a series of biographies, I discover a hidden story that slipped by on the first or even second reading. The notation of praying the Angelus is such an occurrence, yet it appears in several of the accounts—perhaps stemming from different writers citing the same document.

Thoughts on Holy Week

As I cogitated about the La Framboises’ religious piety, I recalled that late-November morning when I prayed through a still-hunt in the river bottom. That has happened a few notable occasions over the last three-plus decades. Such circumstances are as important to me as downing a fine stag or besting a wary gobbler.

As I cogitated about the La Framboises’ religious piety, I recalled that late-November morning when I prayed through a still-hunt in the river bottom. That has happened a few notable occasions over the last three-plus decades. Such circumstances are as important to me as downing a fine stag or besting a wary gobbler.

For me, the Lenten season is a time for reflection, repentance and rededication. On that day, the 18th-century post hunter carried a copy of the New Testament in his hunting bag and engaged in a long wilderness prayer. The historical me’s religious thoughts, prayers and practices mirrored those of the modern me—adjusted slightly in verbiage to reflect my best understanding of 1790 religious practices.

As one might expect, my Lenten reflections have centered on the modern me, not the historical me. As Holy Week progresses that has changed, due in part to the devotion of Joseph and Madame La Framboise. The light of their example, reduced to a sentence or two in modern times, has traveled across eternity’s abyss and impacted the life of at least one traditional woodsman, and maybe more.

In particular, as the returned native captive persona takes shape, I realize that I must address the religious beliefs of this new alter ego. To some degree that has happened, because I am still trying to include a copy of the New Testament somewhere among his material possessions. All along, I have been aware that this character’s world view spans two distinct cultures and that a meaningful portrayal must account for that fact. But for now, at least during Holy Week, the emphasis has switched to religious beliefs and practices. What a glorious,daunting and uplifting challenge…

In this Easter season, be safe and may Christ’s light shine upon you.