An owl hooted early. A wild turkey uttered several soft clucks below its roost tree, somewhere near the sinkhole, not far from the nasty thicket. A misplaced robin twittered as it perched on a dead cedar branch, a few trade gun lengths distant. Within ten minutes the hillside grew quiet and chilling cold. Thanksgiving of 1795 was but a day or two away as a humble woodsman huddled in a single four-point blanket.

A lavender tint backlit the western tree line. Now and again an involuntary shiver twitched a shoulder or snaked up and down the spine. The historical me, the returned captive, struggled with the cold. When he looked to the south, or to the north, warm moist breath fogged frigid brass-rimmed spectacles. A last minute still-hunt offered the possibility of warmth, but instead he adjusted a wool fold over his left ear, the one that doesn’t hear so well. Remaining seated with his back against a scrawny red cedar trunk seemed best.

A muffled crunch broke the silence. A second followed, then another. Not twenty paces distant, just on the other side of a smooth-barked maple, a young buck walked uphill. Only its hind legs rustled the leaves, and then not as much as a cautious chipmunk’s advance.

A muffled crunch broke the silence. A second followed, then another. Not twenty paces distant, just on the other side of a smooth-barked maple, a young buck walked uphill. Only its hind legs rustled the leaves, and then not as much as a cautious chipmunk’s advance.

With his head hung low, the buck glanced north, then south. The evening light faded fast as the buck stopped and sniffed the cool, clean-smelling air. Much to my relief, he stood upwind, but the breeze was but a butterfly’s breath. A maple sapling covered his midsection. I counted six small points, then started counting ribs. My thumb eased up on the cock’s jaw screw, but I still subconsciously prayed, “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord.”

I squinted to avoid eye contact; my upper lip directed my breath down to keep the spectacles clear. The buck took two or three steps. Two cedar trees that grew from a common root blocked his eye. His chest and vitals teased, appealing for the unleashing of the death messenger, but I resisted the temptation.

Four more hoof-falls brought the unsuspecting whitetail even with my lair. He licked his black nose, bobbed it to scent the air, then laid his ears back with a relaxed motion. His head turned slow to the north, then back to the south. Overcome with oblivious miscalculation, his gaze never fell upon my alter ego’s countenance, never comprehended his deathly shape. Minutes ticked away. The security of night’s blackness crept closer. He shook his head, then chose the northerly path. I sat and watched his rump disappear in the darkness.

Period-Correct Cold Weather

Traditional black powder hunting places a varying emphasis on three elements: the traditions or history of a chosen time period, a black powder arm appropriate to that era and fair-chase hunting that mirrors the practices gleaned from researching the chosen time period.

On that particular November evening, I found myself immersed in the late-18th century, 1795, to be exact. My entire deer season focused on that year as I worked on developing the new “returned captive” persona. The fall hunting seasons were cold, an ominous precursor to the winter. Within any traditional hunt, the three elements shift in importance as the circumstances change, but last year, dealing with the cold seemed to constantly overshadow both the Northwest trade gun and the hunt itself.

One of the goals of any traditional black powder hunt is for the participant to become as authentic as possible in his or her portrayal. A living historian can never achieve 100-percent authenticity; I believe that is impossible, given that our historical simulations are just that, re-creations on a 21st-century stage. But after accepting that caveat, we can all strive to get as close as possible.

Recreating the new returned captive persona began with research based on primary documentation. I spent a lot of time reading and rereading the narratives of James Smith, Jonathan Alder and my favorite, John Tanner in an attempt to learn what they wore and what they used. I studied (and still am studying) late 18th-century drawings, sketches and paintings and spent a fair amount of time looking for existing examples of specific accoutrements.

I chose to begin the portrayal with items “borrowed” from the muzzleloading closet that come close to those described in the narratives, seen in illustrations and displayed in museums. I feel writing about this process might help other traditional black powder hunters formulate their thinking as they wander down the path to yesteryear. I have also found that putting the choices into words helps me examine each item within the context of someone who grew up among the Ojibwe but returned to the settlements in later life.

Yet there is an inherent danger in posting pictures and stories as an alter ego takes shape—the vitriolic criticism of the work in progress as not being authentic or period-correct. That is a risk I willingly take, for it is a given when one seeks the knowledge sequestered in the wilderness classroom.

As it is, or should be, with any persona, the choices made try to adhere to what is accepted as “average” or “common” for a given characterization. In addition, an item should be accessible and at the same time, within the financial means of the person owning or acquiring it. For example, a decorated split pouch might be available to a backcountry ranger from a small settlement, but not practical because of the cost in deerskins. But for someone who is living or has lived among the people making the pouch, the Ojibwe or Odawa, the pouch is readily available and the cost is minimal.

As it is, or should be, with any persona, the choices made try to adhere to what is accepted as “average” or “common” for a given characterization. In addition, an item should be accessible and at the same time, within the financial means of the person owning or acquiring it. For example, a decorated split pouch might be available to a backcountry ranger from a small settlement, but not practical because of the cost in deerskins. But for someone who is living or has lived among the people making the pouch, the Ojibwe or Odawa, the pouch is readily available and the cost is minimal.

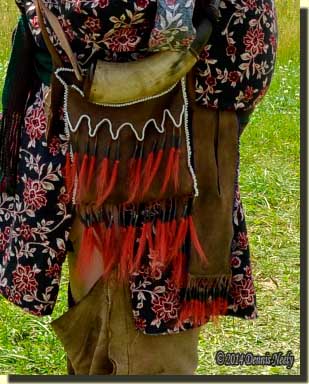

To start out, the new persona adhered to middle of the road choices: center-seam moccasins, buckskin or wool leggins, a breechclout, one or two trade shirts, a wool sash or leather belt, a butcher knife, a tomahawk, shot bag, horn, Northwest gun and a four-point trade blanket. The original plan was to develop the persona as I explored this new path to the 1790s, but as I bounded along that path, overcome with a childlike glee, I bumped into an unexpected obstacle—period-correct, common as the sun rises, cold weather.

From mid-October on, my wilderness classroom lessons centered on surviving that day’s cold. The new historical me failed even the earliest lessons—he couldn’t stay out for more than four hours when the temperature reached 34 degrees. With each outing, a combination of tolerance and understanding slowly pushed the limit lower.

By that late November deer hunt in 1795, 24 degrees was all I could stand without considering striking off on a still-hunt to build up body heat. I am thankful I chose to “tough it out” that evening, because having a white-tailed deer venture within sixteen paces is a huge boost to a traditional hunter’s persona development.

A month later I experienced a similar situation, this time sitting through a snow storm for four hours. The temperature that morning was 18 degrees. I consider that a tremendous accomplishment in persona development, because I learned how to survive in the Old Northwest Territory by adhering to common, middle of the road choices.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.