A fox squirrel chattered, up on the ridge and to the southwest. Yellow maple leaves spun and rocked and tumbled. Sunlight bathed the tree tops; shadows carpeted the forest floor. The night’s chill lingered. Melted frost pitter-patted from the old red oak, for that matter, from all the trees on the hillside.

High up, winging hard, a lone crow cawed steady as it journeyed to the east. Down the hill a chipmunk scurried over and around and upon a grey, rotted stump. Leaf-shadows whipped to and fro on the sunlit trunk of an arching red oak. A gentle gust intensified the shower of cold, wet silvery drips and fall-colored leaves.

Farther down the trail that followed the nasty thicket’s dense edge, a bushy tail flicked on the backside of a clumped maple. Beyond the sedge-grass-filled swamp hole and partway up the knoll a grey squirrel spiraled earthward. And to the left, twenty or so paces up the slope, a third tail teased. Such was the mystique and splendor of that morn, late in October of 1798, two ridges east of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory.

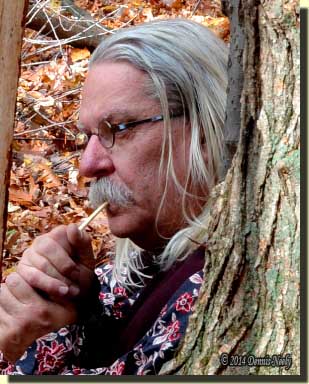

Pulling the green wool blanket about my body, I settled to the ground and eased back against the old red oak. A blue jay wandered by, then perched on a bobbing twig, not too far away. I smiled as the jay canted its head side to side, trying to make sense of my humble being, or so I surmised.

My eyes watched the two fox squirrels, somewhat straight ahead. But my glances longed for a glimpse of a wild turkey, pecking its way along the nasty thicket’s west-side trail. Leaf fragments and a smattering of dirt clung to my new wool leggins. The hand-dyed silk ribbons blended with the leaves, which surprised me and eased my concern. I fought the urge to brush the damp earth off the left knee, hoping for a natural stain.

My eyes watched the two fox squirrels, somewhat straight ahead. But my glances longed for a glimpse of a wild turkey, pecking its way along the nasty thicket’s west-side trail. Leaf fragments and a smattering of dirt clung to my new wool leggins. The hand-dyed silk ribbons blended with the leaves, which surprised me and eased my concern. I fought the urge to brush the damp earth off the left knee, hoping for a natural stain.

Old Turkey Feathers rested on my lap as I sat cross-legged. A healthy swarm of death bees awaited an opportunity to strike. When the blue jay flew off, I pulled my journal from my pouch and began scribbling in earnest. I thought better of that, reached into my shot pouch and retrieved the single wing bone. Drawing in air, I uttered a series of seven even clucks, soft and muffled in tone.

I tucked the bone back in the pouch and returned to scribbling. After each sentence I paused to gander about. Recording the scene before me became a different sort of still-hunt: write and pause, write and pause…

Pursuing a Whimsical Fancy

The fall hunting seasons are in full swing here in Michigan. When a time-traveling opportunity presents itself it is often difficult to decide what to hunt. The ducks and geese are uncooperative; I have yet to see a mallard or wood duck aloft anywhere near the watering hole. Into November the flight ducks will change that. Blue jays, cardinals and robins somehow seem to think they can take the place of an iridescent green-headed drake with cupped wings. And is usually the case, the fox and grey squirrels frolic about when my desires focus on wild turkeys, and vice versa.

The other morning a whimsical fancy overtook Msko-waagosh as he sat in ambush along a doe trail favored by two gobblers. Concealed in the midst of a tree top, surrounded by chattering fox squirrels, the returned captive felt an overwhelming need to feed his hungry family. In a fit of 18th-century exuberance, the Red Fox jumped to his feet. With one swift motion he dumped his prime, wiped the pan clean and lowered the firelock’s hammer. After looking about, the woodsman headed upwind with his mind set on “killing deer.”

To begin to explain this strange behavior, let me start a few days before. I was rummaging through captive narratives in search of references to shelters. Early on in John Tanner’s journal I stopped to read a passage that dealt with an elk hunt:

“In a few days, I went again with Waw-be-be-nais-sa to hunt elks. We discovered some in the prairie, but crawling up behind a little inequality of surface which enabled us to conceal ourselves, we came within a short distance. There was a very large and fat buck which I wished to shoot, but Waw-be-be-nais-sa said, ‘not so, my brother, lest you should fail to kill him. As he is the best in the herd I will shoot him, and you may try to kill one of the smaller ones.’ So I told him that I would shoot at one that was lying down. We fired together, but he missed and I killed. The herd ran off, and I pursued without waiting to butcher, or even to examine the one I had killed. I continued to chase all day, and before night had killed two more…” (Tanner, 65-66)

As with many of Tanner’s stories, there is more intrigue involved with this episode, but the essence of the story is that Tanner killed three elk within the course of one day’s pursuit. The challenge contained within that passage kept eating at me until it grew into an almost uncontrollable, delightful 18th-century compulsion.

Now I have played this game on occasion, based on other journal entries that fit the trading-post hunter persona, but this was the first time for Msko-waagosh. As a traditional black powder hunter, my forays back to the 1790s are shaped to some extent by 21s-century game laws. “Old Turkey Feathers” is always unloaded and there is no intent to actually shoot a deer, they are simply bit players on the living historian’s stage, teachers in the wilderness classroom.

The rules of hunter ethics apply in this game, just as they do under actual hunting conditions. The pursuit must be 100-percent fair-chase, the deer must be within the hunter’s effective distance and the “supposed shot,” taken at a standing deer, must possess a high probability of a quick and humane kill. In addition, only one deer from a group may be considered “dead,” based on the assumption that the others fled at the muzzle’s blast.

Time was limited that morning; a little over an hour remained. Down through the dip and up over the rise I came upon a mature doe, about 40 yards distant. She had no idea a traditional woodsman had crested the hill and lurked behind the fallen, barkless oaks. With her head down, scrounging for acorns, I heard the Northwest gun’s thunderous roar echo through my mind. I felt the recoil, and I believed I detected the sulfurous odor of spent gunpowder.

I slipped away as there was no reason to disturb the “dead” doe. As Tanner did, “I pursued with out waiting to butcher…” My buffalo-hide moccasins angled west. As I paused behind an oak tree, a spotless, spring fawn wandered over the hill and into the valley. She moved at a steady pace. Her frame offered little meat, so I chose not to “take” her and watched her pass by.

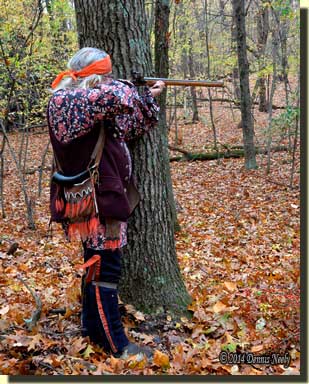

My course pressed south as I circled back to the place of that morning’s beginning. Again, as my shoulder leaned against a tree trunk, a mature doe walked into a small clearing, maybe 30 yards away. When her head was down, I eased back a step and steadied my left hand against the oak. I whispered, “BOOM.” Knowing there was little time left, my mind wasn’t into this “shot.” I imagined the doe ran a bit, then dropped.

My course pressed south as I circled back to the place of that morning’s beginning. Again, as my shoulder leaned against a tree trunk, a mature doe walked into a small clearing, maybe 30 yards away. When her head was down, I eased back a step and steadied my left hand against the oak. I whispered, “BOOM.” Knowing there was little time left, my mind wasn’t into this “shot.” I imagined the doe ran a bit, then dropped.

I wasn’t as fortunate as Tanner. I downed two big does, not three elk. The outbreak of epizootic hemorrhagic disease in 2012 has made such bit players scarce, at least for now. But that makes little difference, because that day’s living history scenario was nothing more than an 18th-century game, a different sort of still-hunt.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.