A cloud line angled southwest to northeast. To the northwest, the sky was clear and deep blue. Overhead the moon’s last quarter shone bright through a break in the dark grey clouds. The canoe slipped silent into blackish water. A ragged ash paddle cut the glassy surface. Water dripped…the paddle pulled, then hooked…water dripped…the paddle pulled, then hooked…

Imitation mallard hens and drakes began their pre-dawn swim in the ripples as the canoe circled in front of an ice-damaged red cedar tree, the one that looks like a feathery arm reaching out to the water’s edge. The cloud line crept to the west. A marsh hawk kited above, flew higher, then swooped down, coming to rest on the topmost branch of tall red oak that showed no fall color.

The canoe’s bow nudged the mucky bank, wedging firm. Ahead and a bit to the right a deer’s haunch hid motionless behind a clump of cedar trees overgrown with wild grapes. What few leaves remained on the vine’s tangled web were pale yellow with noticeable, brown, curled edges.

The deer’s tail twitched. A pesky mosquito buzzed about my right ear. I swatted it. With no time to waste, I stepped ashore. The deer turned to face me. Young and slim, ears forward and head half down, the whitetail watched as I dragged the little vessel through a sparse stand of golden-rod stems. A damp-sounding snap and a couple of pops did not seem to bother the deer. I pulled the canoe into a nearby clump of cedar trees, but did not roll it over.

The deer’s tail twitched. A pesky mosquito buzzed about my right ear. I swatted it. With no time to waste, I stepped ashore. The deer turned to face me. Young and slim, ears forward and head half down, the whitetail watched as I dragged the little vessel through a sparse stand of golden-rod stems. A damp-sounding snap and a couple of pops did not seem to bother the deer. I pulled the canoe into a nearby clump of cedar trees, but did not roll it over.

My buffalo hide moccasins whispered along a short trail that led back to the watering hole and the security of the cedar tree’s feathery arm. I stepped among its boughs and glanced on the water. Overhead the moon’s silvery brilliance dimmed as morning’s first light filled the cloudy heavens. My gaze rested on the western tree line, in the direction of the River Raisin, in hopes of glimpsing a few mallards or maybe some geese seeking a friendly puddle.

“I should know that…”

From the get-go I knew I had an hour at most. Setting out decoys, caching the canoe, retrieving the decoys and securing the canoe take a fair amount of time, but I understood that some 18th-century time was better than none at all.

Handling modern decoys is akin to Richard Collier finding the fateful penny in his pocket, especially when the morning duck chase was measured in minutes. In hindsight, I suppose I tried too hard; my mind never traveled back, but that didn’t really matter. I never saw nor heard a duck or goose. Two Sandhill cranes flew east from the river. To the north, near the narrows in the big swamp, a raspy old hen turkey barked out orders to her brood. A blue jay worked hard at instigating a ruckus. And a little doe stalked downwind of me. I think it was the same one that watched me beach the canoe.

As I waited, surrounded by the majesty of the moment, my mind began to cogitate. I got to thinking about the moon and its phases, then the months of the year and the seasons. One might say a wilderness classroom lesson took shape beside those still waters.

My thoughts took me back to when my maternal grandmother organized one of her nature walks in her back yard. We went tree by tree, having to name each as we wandered down to the garden. In the fall, we had to match the fallen leaves to each tree. She recounted that as a little girl naming the trees was a game the children played on the walk to school. Sometimes the game switched to naming the song birds, sometimes the flowers, sometimes the bugs.

Now I’m pretty good at identifying trees, and descent with birds and mammals. My wild flower knowledge leaves a lot to be desired and so does my recognition of creepy-crawlies, beyond the basic “spider” or “ant” description, of course. As it happened that morning, I scribbled “last quarter” in my journal. That looks impressive, but I only knew that because I observed the full moon a week before, which for me is kind of like cheating—I could hear grandmother scold me.

Normally, if you flipped up a flashcard with an image of the moon, I couldn’t tell you if it was a “waxing” crescent or a “waning” crescent—waxing comes before the full moon and waning after. The same holds true for the first quarter and the last quarter. As a point of reference, the waxing phases appear on the right and the waning phases appear on the left. An 18th-century woodsman would know that, and that realization upset me.

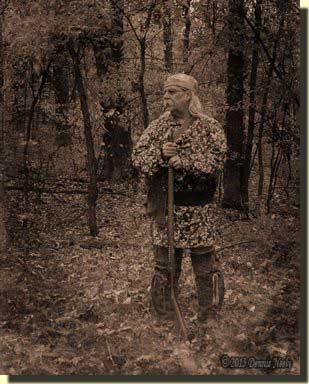

As a dedicated living historian, I spend a lot of time researching historical records to find obscure snippets that will “flesh out” my persona and bring him to life in another time—we all do. The goal is always an authentic portrayal, an honest impression, and as a traditional hunter, I go out of my way to re-create the simple pursuits a hunter hero included in his journal in hopes of experiencing a few seconds of kinship with that individual.

It hurts when you hear Meshach Browning, Josiah Hunt, Jonathan Alder, James Smith and John Tanner all scoffing at you at the same time. Having been in this hobby for a long time, I understand the imagined heckling is a part of the ongoing learning process, a part of defining still another wilderness lesson.

It hurts when you hear Meshach Browning, Josiah Hunt, Jonathan Alder, James Smith and John Tanner all scoffing at you at the same time. Having been in this hobby for a long time, I understand the imagined heckling is a part of the ongoing learning process, a part of defining still another wilderness lesson.

On a different front, with respect to the new persona I have been developing over the past two or so years, I have been a regular Wednesday-night attendee of the Ojibwe Language Webinars offered by Isadore Toulouse through the “Online Anishinaabemowin” site.

That is a tale for another time, but as I chastised my trading post hunter persona for not being able to identify simple moon phases, I expanded my thoughts to include the new alter ego. If an individual was raised by an Ojibwe family, he not only would know the moon phases, but the months and seasons of the year, both in English and Anishinaabemowin. Again, I heard my own grandmother scolding.

The immensity of that concept hurts my head, but in a good way, I think. This is just one more challenge associated with a true and honest impression. To a greater extent, this is not book-learning but rather practical experience gained by immersing one’s self in a characterization while engaging in a woodland pursuit.

After all, my hunter heroes spent a great deal of time outdoors, and even the most inept of the lot would have forgotten more than I know. That’s humbling and frustrating. On the one hand, I can’t begin to devote the hours to my historical Eden that I would like, yet on the other hand, this represents an expansion in understanding the totality of living an 18th-century life in the Old Northwest Territory.

And to think, this whole line of thought evolved from my desire to seek a few minutes of duck hunting beside a friendly puddle…

Slip back to the 18th century, be safe and may God bless you.