Buffalo-hide moccasins crested the ridge. Despite a sense of urgency, the still-hunt progressed with the caution reserved for the stalk of a mighty stag. A lengthy pause allowed a contented grey squirrel ample time to scruff about in the brittle oak leaves, not eight-paces distant. Unaware, the creature scampered to a white oak and spiraled upward. Barely an hour of daylight remained on that pleasant Wednesday afternoon, the first week of November in the Year of our Lord, 1798.

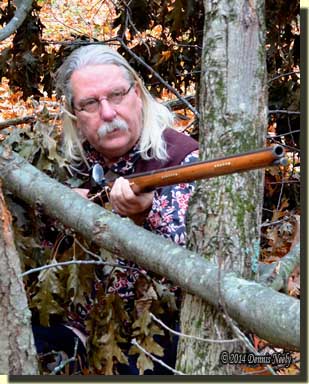

Twenty or so paces down the slope another squirrel drew a pause from the gray-haired woodsman. An additional twenty paces below, a downed treetop offered promising refuge. A gray squirrel ran along the lair’s upper branch, and just beyond, a plump fox squirrel scrounged for acorns on the forest floor.

The squirrels of the lower hillside, four in all, showed little concern as dusty, trail-worn moccasins whispered around the two lower branches. A bedroll slowly descended into the top’s hallowed shadows. With a steadying hand on the upper branch, the returned captive sat. Ribbon-festooned, blue wool leggins crossed and the Northwest gun came to rest on the hunter’s lap.

A chipping sparrow visited next. It perched on one of the dead branches of a scraggly cedar, three trees to the south, and began to serenade. A grey squirrel frolicked in the crunchy leaves, down at the swamp’s edge. Autumn olive sprigs grew thick with more green, fish-shaped leaves clinging than in falls past. A sharp twig fiddled, then clawed at the loose hair atop my head. The twig tangled and dared me to pull the hair free. My fingers broke the pest. The sparrow continued to sing.

A chipping sparrow visited next. It perched on one of the dead branches of a scraggly cedar, three trees to the south, and began to serenade. A grey squirrel frolicked in the crunchy leaves, down at the swamp’s edge. Autumn olive sprigs grew thick with more green, fish-shaped leaves clinging than in falls past. A sharp twig fiddled, then clawed at the loose hair atop my head. The twig tangled and dared me to pull the hair free. My fingers broke the pest. The sparrow continued to sing.

Two blue jays and a crimson cardinal offered pleasing utterances, now and again. I thought better of the peaceful serenity, eased a bit to my right and moved the smoothbore’s muzzle over the branch in front of me, pointing it downhill at the white oak with spreading, stately limbs.

The distinctive sound of scratched-up leaves drew my attention. A wild turkey walked from the sedge grass, following a doe trail that angled back into the golden tamaracks, halfway across the swamp. Anxious to reach a roosting tree, the bird traveled south at a brisk pace.

“Old Turkey Feathers’” sharp English flint snapped to attention when the reddish head passed behind the white oak. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” I prayed in silence.

Almost shouldered, the trade gun halted when the young jake reappeared. Then the wild turkey hesitated, stopping quick in its tracks. Arteries pulsed. My back tensed. Breaths became slow and deliberate. A thick autumn olive whisked away any opportunity that might exist. One minute became two, then three.

The bronze bird never turned its head or looked about. It took a step, then angled closer. I didn’t move, patient to let it come uphill more, knowing I didn’t have a clear line of sight for another dozen or so paces. A half-dozen steps later its head went behind a powder-keg-sized hickory trunk that lined up with a big cedar tree.

The Northwest gun’s tarnished brass butt plate pressed hard against the unbuttoned wool weskit. The turkey kept pace. I estimated three steps to the only clear shot, just to the right of the bushy autumn olive. The turtle sight held tight to his brown eye. An 18th-century moment of truth was upon us…

Pursuing a Pristine 18th-Century Moment

I find it hard to fathom allotting the time to hunt for an entire day, but John Tanner or Jonathan Alder lived under different circumstances than we do today. Lately, there seems to be an abundance of folks touting the improvements of our technologically advanced lifestyle. I find it best to only shake my head and choose not to agree in silence.

Many years ago, I possessed more time to journey back to my beloved 1790s. For the life of me, I don’t know what I did back then to make that happen. In reflection, I worked long hours and had similar family responsibilities, or so it appears. I still work long hours and of late, I’ve spent spare evening minutes finishing the wool leggins, sewing on a new linen shirt, researching an Ojibwe-style winter hood and fretting about cutting out and completing a wool trade shirt before the days get into the mid-20s.

Like everyone else, I wish I could stumble upon the secret, but when I get thinking about it, I’m reminded of the psalm that says “…like olive plants your children around your table…” (Psalm 128:3) Our family has grown and the once adequate dining room table (when it doesn’t have my work files stacked on it) cannot hold us all. What a blessing!

My good hunting companion, Darrel, suggests it is simply the progression of years, but I refuse to accept “old age,” as he calls it, as a reason. Besides, his voice always has a telling grin about it, so I suspect he is just egging me on.

Either way, time is limited for seeking out pristine moments to share with our hunter heroes. The last couple of years, I find myself eager to don my backcountry clothes when only an hour or two pops up. With that in mind, I keep my kit laid out on the bed in the guest room and I can transform from ugly caterpillar to my version of an 18th-century butterfly in less than ten minutes.

On that evening, I had an hour and twenty minutes before dark set in, which included dressing and traveling. Even with that tight constraint, I engaged in a serious stalk of the downed tree top. I thought that at the least I could sit for thirty minutes and walk out by moonlight, which I so often do.

Coming so close to the first grey squirrel was a tremendous traditional black powder hunting experience. Zigzagging down the slope without disrupting the other squirrels, blue jays and cardinal heaped on more joy and personal satisfaction. Moving “Old Turkey Feathers’” muzzle over the branch in light of the soothing solitude of that evening represented the positive hope of getting another chance and maybe bagging a wild turkey.

In all, the time line from parked pickup to standing over a dead fowl spanned no more than 35 minutes. I did not need a whole day or an afternoon dedicated to romping in my historical Eden; an hour and twenty minutes proved more than sufficient, climaxing with a pristine18th-century moment I shall never forget…

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!” A yellow tongue of fire belched from the smoothbore’s muzzle before I gave conscious thought to releasing the death bees. In hindsight, I realize I never heard the thunder. Years of 18th-century experience ruled that instant, as I’m sure it must have for John Tanner or Jonathan Alder.

Leaning right, I peered under the rolling cloud of thick, white sulfurous stench. Outstretched black and gray feathers flailed against the leaves. I gained my feet and picked the shortest path around the autumn olives to the bottom of the hill.

A buffalo-hide moccasin anchored the young jake’s motionless purple legs. I looked about to make sure an intruder did not hear the shot, for the Northwest gun was empty. In due time I knelt over the lifeless wild turkey that gave its life to feed my family, and I gave thanks to God for a clean kill and a positive answer to my constant supplication.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.