A button buck stood and stared. Thick black hair bristled down the top of his neck, not long, but noticeable. The black mane, a genetic trait that first appeared forty or so years ago, shows up from time to time in the white-tailed bucks that frequent the River Raisin’s bottomlands. Like his wily ancestors, this wise-beyond-his-years youngster sensed danger lurked close by while others sauntered north, unconcerned.

Ten minutes before, on a cold December morn in 1798, six deer exited the big swamp and plodded into the sunlit hardwoods that populated the basin-like valley. The group turned north, single file, two fawns trailing two does in order. The button buck emerged last and followed up, maintaining about a fifteen-pace distance. He seemed to lollygag behind, taking his time as he glanced about. When he turned his head, the sun highlighted two auburn colored bumps the size of Brown-Bess musket balls, leaving little doubt as to his gender.

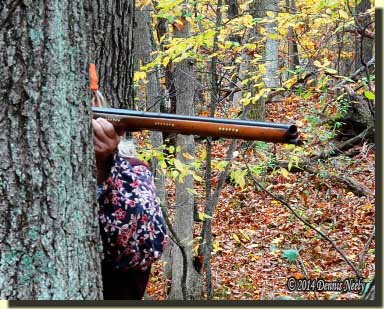

The six moved on at varying paces, bunching up, spreading out and bunching again. The middle doe paused at the point where the trail came closest to my lair, a twisted box elder tree growing close to an almost dead red cedar tree, thirty paces uphill. She craned her neck, licked her nose and then bobbed her head up and down, trying to get the scarlet-blanket-clad woodsman that sat in the brush to betray himself with a subtle movement. After a dozen or so attempts, the doe gave up and the six walked over the knoll and out of sight to the north.

But the button buck lingered, standing motionless with his body shielded by a red oak tree and two clumps of autumn olive. He displayed no desire to keep up with the plodding entourage. Instead, he peered out into the swamp, checked his back trail, glanced uphill and half-dropped his head with his eyes fixed on the trail ahead. But he did not budge.

But the button buck lingered, standing motionless with his body shielded by a red oak tree and two clumps of autumn olive. He displayed no desire to keep up with the plodding entourage. Instead, he peered out into the swamp, checked his back trail, glanced uphill and half-dropped his head with his eyes fixed on the trail ahead. But he did not budge.

At least ten minutes passed, then he began his own still-hunt up the slope: one step, then a long pause, another step, another hesitation…

When he came even with the box elder, he sniffed the air and spent a fair amount of time surveying the hillside in all directions. A broken down autumn olive bush separated us like an old fort’s palisade; once in a while I caught sight of an ear or his shiny black nose.

For no apparent reason, the button buck commenced a steady walk up the hill, stopping eight or nine paces shy of the ridge crest. Still upwind of my lair, the wilderness classroom lesson continued—for both of us. Again, tedious minutes passed, filled with sniffs, nose licks and glances to all points of the compass, and some in between. A resumed still-hunt occupied the next dozen minutes before the young buck’s tail flicked side-to-side and he disappeared over the rise.

A Change in Habits

In an email exchange a week ago I lamented to my good friend and fellow traditional hunter, Darrel Lang, that I was disappointed that it had been a while since I posted a new missive to this blog. He offered a possible post, short and sweet:

“Gone to the woods to hunt deer! Will return when the season is over or my tag is filled!”

Engaging in as many traditional black powder hunts as I could was a major goal coming into the fall. Squirrels, ducks and wild turkeys occupied most of my efforts in October, and Canada geese and turkeys took center stage in early November.

By the start of Michigan’s firearm deer season, the weather was like that of late December, except colder than last year. The three worst days of the first week, I reverted to the trading post hunter persona, because his clothes are warmer than those of Msko-waagosh, the returned white captive. But I refused to give up, and on the Friday after Thanksgiving, Red Fox tolerated a calm, 10-degree morning in the glorious Old Northwest Territory, bettering last year’s comfort level by a whopping eight degrees.

Although I have not yet filled a tag, more by my own choice than a lack of opportunities, the fall has been a tremendous success, especially the white-tailed deer season. But the definition of what constitutes “success” is where the traditional hunting philosophy parts ways with modern, high-tech adventurers.

Many of my 18th-century sojourns have included failures, most minor, across a broad spectrum of topics: clothing, accoutrements, techniques, 1790’s skills and woodland knowledge. To be fair, a contributing factor was, and is, the addition of several new or refined items of material culture that in the midst of a simple pursuit didn’t perform in the same manner as a hunter hero once described. Yet, keep in mind that for the traditional black powder hunter such failures are really success stories—practical, hands-on discoveries of a history-based, backcountry lifestyle.

Many of my 18th-century sojourns have included failures, most minor, across a broad spectrum of topics: clothing, accoutrements, techniques, 1790’s skills and woodland knowledge. To be fair, a contributing factor was, and is, the addition of several new or refined items of material culture that in the midst of a simple pursuit didn’t perform in the same manner as a hunter hero once described. Yet, keep in mind that for the traditional black powder hunter such failures are really success stories—practical, hands-on discoveries of a history-based, backcountry lifestyle.

An Ojibwe-style man’s hood, fashioned after several museum artifacts attributed to this region, is the latest culprit. But learning to live and survive with the personal possessions attributable to a given bygone era is an integral part of all wilderness classroom lessons—frustrating, thought provoking, educational and fun, all at the same time. And many of these lessons will eventually make their way into my scribblings during the coming year.

But the most profound and noticeable challenge is the change in the habits of the white-tailed deer. In 2012, epizootic hemorrhagic disease decimated our deer herd. The death toll was heaviest among the older does, the teachers of the herd. I saw more wild turkeys than deer that fall. Last year was an improvement, but several close-by deer hunters and I noted that the does with fawns seemed small and didn’t adhere to the time-tested travel patterns of their mothers.

Throughout the summer and into the fall, this change became more evident. The deer still exhibited natural survival skills, but in different ways than the deer that succumbed to EHD. By mid-October doe trails that once were churned-up earthen thoroughfares sat idle, strewn with leaves. Some deer went this way, while others went that way. A humble observer can only assume they all reached their intended destinations, which is, after all, the intent of their journey.

When the cold and snow of early November hit, the deer traveled in groups like they did decades ago. With the passage of multiple deer, trails formed in the snow and other deer followed the paths already broken. But these habits were new to this generation of deer, born out of wilderness survival necessity, rather than generations of experience.

And so it was that cold December morning in 1798. The six bunched up and spread out as if they were feeling their way through the dense cedar trees for the first time. I doubt that was the case, but that was the impression left, and there is no way of knowing.

As the button buck picked his way up and over the ridge, I found myself cogitating as he progressed. Here I was, a new character conceived in the fall of the EHD outbreak, feeling my way through a unique living history circumstance, establishing thought patterns different from those of the fort hunter persona.

In the time that it took the young buck to traverse the sunlit hillside, I realized the magnitude of putting forth the effort to spend more time afield this fall. The resulting trials and tribulations bestowed upon me a wealth of new knowledge, along with a host of tantalizing questions and possibilities. I had, at least temporarily, sacrificed writing time for an opportunity to breathe meaningful life into a blossoming characterization. And that is, after all, the intent of this glorious journey.

So head to the woods, be safe and may God bless you.