Two hens walked straight away. The pair stayed in the dirt path; their actions seemed unnatural, reluctant. Crisp putts hung in the still cold air. The two wild turkeys hugged the windrowed snow pile filled with uprooted cornstalks as they returned to the main flock. One by one, bluish heads popped up. I counted nineteen in all, including a couple with red heads and decent beards.

At the far end of the strung-out flock, one of the bigger birds stepped over the snowy barrier and started walking fast on the ice-crusted accumulation. Others followed, single file. As if required to pass through some imaginary door, the bronze birds made their way to the spot where the bold one jumped the bank and ran into the corn stubble. Forty paces from that portal, almost at the crest of the hill, the turkeys took flight, again, one after the other.

It was not my intent to spook the turkeys, but I had little choice as I returned to the pickup. They were feeding on the only open ground, a makeshift road plowed at the edge of the cornfield by a subcontractor for the power company. On purpose, I ventured back to the North-Forty at noon, thinking the field would be void of wild creatures. I was wrong.

It was not my intent to spook the turkeys, but I had little choice as I returned to the pickup. They were feeding on the only open ground, a makeshift road plowed at the edge of the cornfield by a subcontractor for the power company. On purpose, I ventured back to the North-Forty at noon, thinking the field would be void of wild creatures. I was wrong.

A ways down the wagon trail a plump fox squirrel jumped from the back of an oak trunk, rolled once on the snow and ran west in the left rut. At the shag-bark hickory, another fox squirrel joined the parade. A third followed, again from behind another hickory. I laughed at the foolishness.

Across the sand bridge and up over the rise, I discovered two more fox squirrels enjoying the sunny, but cold February afternoon. I started to wonder if a squirrel hunt wasn’t a better use of my time. I saw four more before the truck came to a halt.

Testing a “Buck & Ball” Load

Eighteen inches of fluffy snow made accessing the range all but impossible. Three days after the snow, the work crew cleared off a staging area for the line work in what we call “the first right of way,” adjacent to the big woods. I found a suitable snow pile just down the hill and propped up a cardboard target sporting a cartoonish outline of a coyote. I counted back thirty-five paces and scuffed a mark on the dirty ice.

Coyote predation has become a big problem in our area. To combat the invasion, I run a predator trap line from mid-October into December, depending on weather. With November’s weather more like late-December, I got frozen out early this year. Calling is the second best choice.

Jeff Wacker, my neighbor to the north, has been doing some coyote hunting. We talk on a regular basis and had planned to hunt the North-Forty until the snow made it difficult to get back in. Jeff uses a modern rifle with a scope, but I don’t own one—once again, “Old Turkey Feathers” is my “go-to gun.”

Years back, I had an opportunity to do some bobcat hunting north and east of Grayling, here in Michigan. I worked up a satisfactory load of #3 buckshot and felt comfortable with the performance out to thirty paces. I’ve used that same load a couple of times on coyote hunts, but never had a coyote venture that close.

Although the cover we plan on hunting is dense, I would feel better if I had a little more range. Loading with a round ball is a possibility, but after 45 yards a coyote’s vitals get mighty small for consistent shot placement on my part. As I mulled over the options, I got thinking about a compromise, perhaps a buck and ball load?

I made a few phone calls to other traditional black powder hunters, but only one person had ever shot a buck and ball, and that was during a novelty shoot. No one had any credible practical information on this 18th-century load. As is always my habit, I checked my research files, then went looking for other sources of information.

The “suggested” buck and ball loads involve loading the ball first and then the buckshot. If no wadding is used between the powder and projectiles, as in the case of a paper cartridge, the ball is supposed to create a better seal. From an historical perspective, I found no primary “how-to” documentation, and none of the speculative sources offered sample targets or range results.

Competitive quail walk and sporting clays experience taught me that a “split,” “spreader” or “duplex” load, a load divided by a card placed within the shot column, creates a wider pattern. Although not allowed by at a lot of ranges, the duplex load works great on close in targets such as rabbit discs and low-flying, over-the-head clays.

In essence the back shot column blows through the front column, spreading the front column in a shorter distance. From my own testing, I discovered the intermediate card placement is critical in maintaining a uniform, yet broad pattern. I feared the same would happen with the buckshot over ball loading sequence, the ball would blow through the buckshot spreading it farther. That would be fine for warfare, but not good when the end result was killing a coyote at a fair distance.

A couple of years back, another traditional hunter sent me an x-ray image of a 1769 Short Land Pattern Brown Bess retrieved from a revolutionary-war-era shipwreck off St. Augustine, Florida. The musket’s buck and ball load has the buckshot loaded first with the ball over top, which is more consistent with my shot patterning experience.

Since I felt like I was flying by the seat of my pants, safety became the first concern as I did not want to overload the trade gun or create a “short-started” load. To start, I checked my notes from the bobcat load, which included 24 pellets, weighing a total of 560 grains. I wrote that four pellets fit in a layer, so to remain tight and uniform, the pellet count needed to be a multiple of four.

Since I felt like I was flying by the seat of my pants, safety became the first concern as I did not want to overload the trade gun or create a “short-started” load. To start, I checked my notes from the bobcat load, which included 24 pellets, weighing a total of 560 grains. I wrote that four pellets fit in a layer, so to remain tight and uniform, the pellet count needed to be a multiple of four.

Next I weighed a normal turkey load, which scaled out at 571 grains. Although my notes didn’t show it, I wondered if I used the same rationale for the bobcat load? Old Turkey Feathers prefers a .610 round ball, which weighs 345 grains. Using 560 grains as the maximum load left 215 grains, or enough room for nine #3 buckshot. With four pellets to a layer, the test load was a .610 round ball and eight #3 buckshot.

At the makeshift range, I measured out 60 grains of 3Fg Goex (equivalent to 75 grains of 2Fg) black powder, added leaf wadding over the powder and counted out eight #3 pellets. I rammed a minimum amount of wadding over the buckshot, dropped the ball down the barrel and wadded the ball tight. [Note, I am not making load recommendations here, because every smoothbore is different. I am only reporting the load I used in my trade gun.]

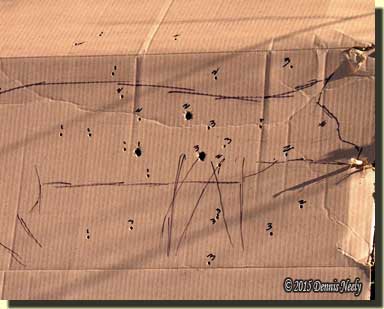

Three shots later the cardboard coyote had three musket balls and twelve buckshot in the chest and body area. At 45 paces only one musket ball hit the coyote; the other two passed under the would-be predator. The pellet pattern opened up with six hits. The last three shots and the buckshot pattern were still consistent, but about five inches low.

Three shots later the cardboard coyote had three musket balls and twelve buckshot in the chest and body area. At 45 paces only one musket ball hit the coyote; the other two passed under the would-be predator. The pellet pattern opened up with six hits. The last three shots and the buckshot pattern were still consistent, but about five inches low.

A bare ball group is usually more open and hits a little lower than a patched grouping, all loading elements remaining equal. A light patch should raise the balls into the kill zone, and I expect tighten the ball grouping. I don’t know what effect, if any, a patched ball will have on the buckshot pattern.

Looking at the results makes me wonder how a heavy-patched .575 round ball (285 grains) over twelve #3 buckshot (280 grains) might perform. Perhaps a balanced projectile column would put more pellets in the kill zone. The general idea is to still kill the coyote at 45 paces if the round ball misses.

Aside from having a lot of fun and gaining new knowledge, I view the buck and ball test results with mixed feelings. At best, regardless of load type, the farthest effective distance of the Northwest gun on coyotes is 45 paces—with a round ball, due to my shooting ability, and with the buck and ball the limiting factor is the gun/load’s performance.

More range time and experimentation in the wilderness classroom is necessary. I want to test a patched round ball and the balanced load using the .575 death sphere. Plus, I feel the buckshot over ball load needs a fair airing. Other than establishing the basic limitations of the trade gun on coyotes, I came away with more questions than I started with. But like so many aspects of living history and traditional black powder hunting, the deeper I delve into my beloved 1790s the less I really know.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless.