Two hard rains swelled the River Raisin. A humble woodsman stood on the first knoll to the east of the lily pad flats. Bright, mid-morning sunlight turned the coffee-brown waters a stunning azure blue. A solitary white swan paddled against the current. Overhead, a cold, northwest wind whipped the budding treetops. Mouse-ear-size leaves dotted the autumn olive branches, and in the bottoms, ankle-high skunk cabbages offered the only hint of late April’s greening.

With reluctance, buffalo-hide moccasins turned away from the river and stalked across the opening where a canoe-tarp lean-to offered refuge a dozen Octobers before. At the base of the hill, the wind gusted with a noticeable rush, almost moaning. A dead oak twig cartwheeled earthward with a faint clatter. Back behind, at the edge of the bottoms, the barkless, upper half of a keg-sized maple trunk, a ‘widow maker’ as some call it, hung suspended in a stouter sibling as it had for the last five or so winters.

With reluctance, buffalo-hide moccasins turned away from the river and stalked across the opening where a canoe-tarp lean-to offered refuge a dozen Octobers before. At the base of the hill, the wind gusted with a noticeable rush, almost moaning. A dead oak twig cartwheeled earthward with a faint clatter. Back behind, at the edge of the bottoms, the barkless, upper half of a keg-sized maple trunk, a ‘widow maker’ as some call it, hung suspended in a stouter sibling as it had for the last five or so winters.

Farther east my moccasins paused beside a shag-bark hickory tree. A fine buck fell to “Old Turkey Feathers,” thirty paces south, twenty-plus seasons ago. Straight ahead a ten-pointer provided winter sustenance, and just to the right of that a young buck parlayed with the death messenger. To the northeast a long-bearded gobbler came home for supper and just over the hill the death bees swarmed about an unsuspecting wild turkey in the midst of a sudden October thunderstorm.

The air smelled damp, plain and ordinary. White clouds moved with haste, now and again blocking the golden orb and plunging the forest into a foreboding, dusk-like shadow. A hearty dose of recollections spiced my thoughts on that blustery morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

Overcome with an aimless wander, my moccasins made their way around the huckleberry swamp, through the black locust stand and up the next rise. Nine cobblestones, gathered with some effort, rested in a neat pile beneath a modest red oak. A dead limb dislodged by a violent rainstorm the summer prior lay across the site of long-gone canoe-tarp camp.

I leaned against the oak, then thought back to the warm afternoon in late September spent constructing that fall hunting camp. I remembered looking up into the trees to make sure no widow makers lurked. The branch was not dead then, but times change and life in the forest progresses along on its endless journey to eternity.

Recollecting the Past

Sometimes unusual 21st-century circumstances facilitate 18th-century time travels. Last week I spent a morning rummaging through three of my earliest photo albums, searching for a specific image. As the pages flipped one after the other, I couldn’t help but pause now and again to relive some of those first traditional black powder hunting adventures.

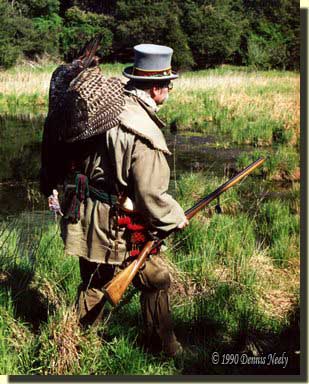

A couple of the pictures kept eating at me, so later that evening I pulled out one album in particular and took a closer look. What caught my eye was the grey felt top hat I use to wear. That top hat was a Christmas gift, back in the early 1980s. In a passing conversation I had mentioned that I had found several images of fur trade clerks wearing top hats and my brother acted on my comments. The following winter I added a dark brown buckskin hat band, adorned with a seed-bead, Ojibwe-style floral design.

Back then I wasn’t paying much attention to the “who,” “when” and “where” of living history: the life station of the person I wished to emulate, matching the time period of the images to the 1790s, or focusing on the lower Great Lakes region. Spurred on by romantic thoughts after missing a six-point buck with a Civil War reproduction Zouave rifle, my only desire was to try to discover what it was really like to hunt in a late-18th-century manner.

Until I began reading Mark Baker’s column, “A Pilgrim’s Journey,” in MUZZLELOADER Magazine in the late 1980s, I had no idea what I was trying to accomplish had a name: “living history.” The Northwest trade gun didn’t have a name then, either.

On a couple of occasions, in the heat of a deer chase, I realized my mind had slipped into another century. Again, it was Mark Baker’s writings about Professor Jay Anderson’s theories on “time traveling” that introduced me to the idea of seeking out “pristine historical moments:” fleeting points in time when a traditional woodsman’s experiences match those contained in the journal of a long-dead hunter hero.

By the early 1990s I began re-examining the historical basis behind my trading post hunter persona. Following the example set forth in “A Pilgrim’s Journey,” everything came under scrutiny, including the grey felt top hat. By then, the top hat was a loyal and welcomed companion for most of my sojourns; it appeared in many photographs. As an aside, I feel compelled to note that wearing hunter orange was not a regulation when all this soul searching took place.

By the early 1990s I began re-examining the historical basis behind my trading post hunter persona. Following the example set forth in “A Pilgrim’s Journey,” everything came under scrutiny, including the grey felt top hat. By then, the top hat was a loyal and welcomed companion for most of my sojourns; it appeared in many photographs. As an aside, I feel compelled to note that wearing hunter orange was not a regulation when all this soul searching took place.

But the primary documentation and late-18th-century illustrations and paintings did not corroborate the hat’s style—at best attributed to the late 1820s. Disappointed, I set the hat on a shelf where it now collects dust. I still wore an orange wool tuque in the winter, but I switched to wearing head scarves or no hat at all.

When I found the image I was looking for, I saw the top hat first off. My stomach rolled; my heart pounded; and I felt ashamed. I looked for another image, one without the hat, but there were none—deep down I knew that. In the moments that followed, I vacillated on whether or not to include the image with the article, but the grey top hat with the beaded band is an integral part of the story of my alter ego’s journey back to the 1790s.

Traditional black powder hunting is a learning experience. In the early years, with flintlock in hand and outfitted in “questionable” historical garb, I just wanted to hunt like our ancestors had. Guided by my “best understanding” of the past, I put food on the table in what I thought was a period-correct manner.

A decade later, that best understanding had changed; I put food on the table, and did so in what I thought was a period-correct manner. Another decade passed, and then another…I put food on the table, and did so adhering to my best understanding of what hunting in the 1790s was all about.

In another decade, my traditional hunts will seem like so much foolishness, just as those a decade ago appear today. But this is the wondrous attraction of traditional black powder hunting, a life-long learning experience, an endless journey to eternity.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to An Endless Journey to Eternity