A close approach proved impossible. The two toms roosted high up in an oak tree that leaned north on the first island. The pair walked onto the wooded mound the evening before. Dawn’s greyness, accentuated by a thick cloud cover and a thin, damp fog, gripped the fen and the surrounding forest.

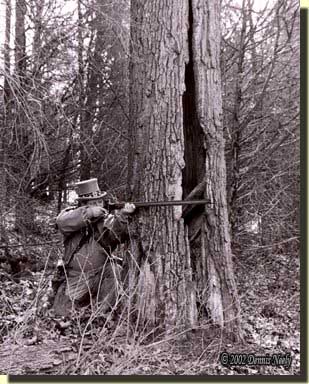

The old red oak has always been a favorite lair. In the days before Michigan required hunter orange, I thought the gray top hat with the Ojibwe-style beaded band was period-correct. How times have changed…

Soft elk moccasins, new at the time, whispered down the slope. Near the base of the hill on the east side of the big swamp a red oak skeleton stood. The tree is still a favored haunt. The topless monarch is hollow. The west face carries a nasty lightning split. Copper-colored rotted wood, half-hidden under raccoon dung, rests knee-deep in the shell. It was mid-April, in the Year of our Lord, 1790.

Around the bend, a hushed “putt” broke the morning’s serenity. A stern-sounding “arrk” echoed out over the dense cattail patch. A different hen started a long yelp. “Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl! Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” Both toms cut her off after the second cluck. Much to my pleasure, the wild turkeys chatted for the next twenty minutes.

I tried to listen to the hens, memorizing their cadence and counting the number of clucks. When a yelp began, I sucked air as if a wing-bone call rested between my lips. I dared not attempt to respond, first because the spring turkey season had not yet begun, and second because my laments would be lost is such a furor. On that morn I did not want to be deemed another sex-crazed hen by a wary gobbler—a humble woodsman has standards, you know.

Instead, I sat on the cleared ground behind that oak tree with the prickly thicket to my right, content to watch and listen and learn. Toward the end of the rants, one of the two gobblers on the island switched tone. He gave a startled, shortened gobble, then some sharp putts and a popping-like cluck.

Four different sets of big wings flapped on the far ridge. A cluck here and a distinctive putt there told that the birds were moving fast to the south. To my right, still roosted, a hen uttered a six-note yelp. A different bird answered with ten clucks, rapid and agitated. The first hen mimicked the long diatribe; mixed in the middle of her sentence I thought I heard a coyote’s bark. The second yip left no doubt. The toms gave a double gobble and the hens began putting.

It was then that I wished the Northwest gun that rested across my lap held a hearty charge. A couple of minutes passed, then two hens flew to the right of my lair, coasted over the island and landed on the ridge crest. The toms took flight and joined the hens. Then the big swamp grew quiet.

Traditional Hunting’s Excellent Safety Record

“Favorite turkey load” is always a popular discussion point on the eve of spring turkey season. When the topic comes up, I never cease to be amazed at the lack of attention to detail or the willingness by some traditional black powder hunters to offer “tried and true” loading recommendations, especially when it comes to powder charges.

Traditional black powder hunting and the black powder shooting sports have an outstanding safety record—the result of decades of hard work and education. A large portion of the credit for that accomplishment goes to the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association for their steady vigilance in promoting the safe and proper use of black powder as a propellant. Most of the muzzleloading clubs around the country, the world for that matter, adhere to the NMLRA’s safety rules and regulations.

A second excellent source of information is The Complete Black Powder Handbook by Sam Fadala. I believe the 5th Edition is the current work, published in 2006. There are other reputable sources, but these are the first I go to when a question arises.

As living historians, we must all recognize our chosen time period came with no disclaimers, no guarantees and no “do-overs.” Each individual was responsible for his or her own actions—along with the “period-correct” consequences that accompany not paying attention to important details.

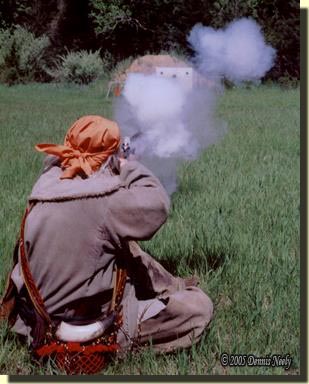

The same holds true for the handling of the arms associated with a given time period, station in life and geographical location—the “who,” “when” and “where” of living history. The individual is responsible for knowing and understanding his or her arm and the safe handling, loading and shooting procedures associated with that specific shooting iron. And coupled with that understanding is the implied responsibility to practice at the shooting range until a minimum level of competency is acquired to safely use the gun in the heart-pounding adrenalin rush of an actual history-based hunting situation.

When talking about a favorite load, I try to preface my comments with “this is what I have found works best in ‘Old Turkey Feathers,’” or whatever arm I am referring to. That caveat is based on actual research of proper load parameters, extensive range testing and years of hands-on experience in the field, all with safe operation as the primary consideration for establishing an efficient hunting-load choice.

When talking about a favorite load, I try to preface my comments with “this is what I have found works best in ‘Old Turkey Feathers,’” or whatever arm I am referring to. That caveat is based on actual research of proper load parameters, extensive range testing and years of hands-on experience in the field, all with safe operation as the primary consideration for establishing an efficient hunting-load choice.

In addition, I have a number of friends with a solid knowledge of modern ballistic science. When I have a specific question, I go to them for an explanation of the factors that are acting on whatever problem I am studying.

Most of my ballistic knowledge is based on actual hunting situations, because my concern is with achieving an acceptable level of accuracy that assures a clean and humane kill. Thus the bulk of my attention focuses on modest loads that produce a tight group or pattern and sufficient projectile penetration to get the job done, quick and neat.

FFg vs. FFFg Granulation Breech Pressures

The arms we use for our traditional black powder hunting adventures are designed to use only black powder or an approved black powder substitute, such as Pyrodex®. Never use modern smokeless powders in any rifle, shotgun or pistol designed for black powder.

Just because these muzzleloaders and black powder cartridge arms are reproductions of what some people characterize as “ancient technology” does not mean they are simple. They are not. There is a minimum level of care and concern that must accompany the safe use and handling of the guns from yesteryear.

When I first started down this path, the rule of thumb was that one used FFFg (refered to as “3Fg”) black powder in a gun of .50-caliber and smaller and FFg in larger bores. In recent years, this principle has fallen by the wayside, and today a majority of black powder shooters use 3Fg in their smoothbores, pistols and rifles, because of its cleaner burning properties that result in less fouling.

The “Fg” designation refers to the size of the black powder granules and is meant to maintain a level of uniformity from batch to batch and manufacturer to manufacturer. For common granulations, Fg is the coarsest and 4Fg is the finest, although finer priming powder granulations are sometimes available.

The chemical composition is the same regardless of granule size, but the burning rate and resulting breech pressure increases as the kernel size gets smaller. The burn rate is due to the exposed surface area: a granule of Fg takes longer to burn and produces less pressure than a kernel of 3Fg, for example. Due to its small size and high pressure, FFFFg, or 4Fg, powder is never used as a propellant, only as a priming powder.

Because each granulation produces a different breech pressure, any black powder load discussion that includes mention of a powder charge must specify the granulation used. But in the last couple of years, “favorite load discussions,” especially on Internet forums, chats and web postings, have started ignoring the difference between the two common granulations of black powder used for traditional hunting: 2Fg and 3Fg. This is a huge mistake with the potential for creating life and death consequences!

The comparison between the two granulations most often quoted is that 3Fg produces 25-percent more breech pressure than the equivalent charge of 2Fg. I have asked, but never been shown test data to support or refute this percentage, but 25-percent seems to be the accepted differential. If you know of a documented source, please share it.

The importance of this comparison is apparent when switching from 2Fg to 3Fg. An established powder charge of 85 grains of 2Fg must be adjusted to compensate for the 25-percent increase when converting to 3Fg, or to 68 grains of 3Fg. To do so, the grain measure of 2Fg, 85 grains, is divided by 1.25; and to convert a 3Fg charge to a 2Fg charge, the 3Fg grain measure is multiplied by 1.25. But when making any conversion from one granulation to the other, one must realize that range practice is required to produce the similar results.

In addition, when loading shot the standard axiom is to load an equal volume of shot to an equal volume of black powder using the same measure. The new 68 grain charge of 3Fg requires a smaller volume measure than the 85 grain load of 2Fg, which unbalances the overall shot column. At the patterning board, I found that a measure and a third produced the desired results. And because bismuth shot is lighter than lead, I had to make some adjustments in my waterfowl load, as well.

This time of year, when folks tend to share “favorite turkey loads,” make sure the individual specifies which black powder granulation he or she is using, and remember to do the same when you enter the discussion. And beyond that, understand that the stated load is for someone else’s black powder arm and not yours. Temper their experience with diligent range experimentation and keep safety to the forefront of your thoughts at all times.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.