Oak leaves sprouted a few days ago. The maple and wild cherry trees are well ahead, almost complete. The lone shag-bark hickory to the north sports leaves the size and shape of a half-grown cottontail rabbit’s ears. Ahead and to the right, witch hazel leaves flutter in the cold, penetrating west wind. Patches of trilliums dot the forest floor like mythical Lilliputian umbrellas—some concealing round flower buds. If not for spring’s explosion of green, a humble woodsman might think it mid-October, not mid-May of 1795.

Three days of rain pushed the River Raisin beyond its banks. To the west the river is sky blue and appears summer warm, to the north November grey, frigid and threatening. To the west, lush canary grass stems grow waist high, but to the north, weathered, broken and tangled cattail stems offer a bleak reminder of winter’s harshness. Such are the circumstances of a woodland tenant in the Old Northwest Territory.

Three days of rain pushed the River Raisin beyond its banks. To the west the river is sky blue and appears summer warm, to the north November grey, frigid and threatening. To the west, lush canary grass stems grow waist high, but to the north, weathered, broken and tangled cattail stems offer a bleak reminder of winter’s harshness. Such are the circumstances of a woodland tenant in the Old Northwest Territory.

The sharp honks of Canada geese that flew in at first light punctuate the melodic warbles of red-winged black birds. Two white swans paddle against the current adjacent to the mud flats where lily pads float like emerald isles on an azure sea. Down the hill, calf-deep skunk cabbages carpet the soggy peat of the river’s bottom land.

I have yet to hear a wild turkey’s “arrkk,” or “cluck,” or “putt;” nary even an aborted gobble. But the birds often remain silent in a steady breeze such as today—nonetheless that never quells the joyous anticipation for what the next moments hold.

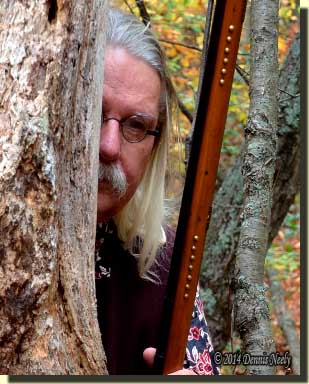

My back rests against a modest white oak as I sit cross-legged on a wool blanket roll. The Northwest gun, charged with a healthy swarm of death bees, lies across my wool leggins. A thinning juniper, reaching chest-deep on my human shape, encircles the north side of the lair. I am only half-hidden. “With the hens on the nest my best hope is to glimpse a bright red head with a shimmering bronze body as it picks its way through the greenery,” I scribble on a folded page.

Based on careful observation, I knew a mature hen had a nest just over the hill to the south, among the downed poplars and the large fallen red oak. Two hills over, another hen frequented the hardwoods to the northeast of the yellow tree, or so I surmised from her travels. In past years, long-bearded gobblers skulked through the crease where the bottomlands meet the oaks and cherries and hickories of the higher ground as they journeyed from nesting hen to nesting hen. Armed with that knowledge, on a cold May morning, Msko-waagosh waited in ambush.

The Power of Observation

To be honest, I am a bit envious of hunters, modern or traditional, who walk into the glade, sit down next to any tree, yelp nonstop for twenty minutes and have a mature tom waltz up in full display with a sign swinging from its neck that says “Take me, I’m yours.”

That scenario seems to be the popular storyline for this year’s spring turkey season, at least here in Michigan. I’m beginning to wonder if some unknown side effect associated with traveling back in time has befallen the wild turkeys on the North-Forty. My neighbor to the north, Jeff, who is also a traditional black powder hunter, and I discussed this topic yesterday. We both are scratching our 18th-century noggins, because our birds are few and far between, and the toms that are out there have the best anti-hunter security system we’ve ever seen.

As Jeff lamented, we have both killed a lot of gobblers, but the days of calling nonstop and having a longbeard strut right in, with or without a decoy spread, are long gone—at least with our flocks. This year’s colder weather and the resulting delay in spawning takes some of the blame for the turkeys’ evasive habits, but a significant increase in poor calling is the big culprit.

For the last ten years we’ve had to deal with younger birds being educated by all manner of unnatural-sounding enticements, and the older turkeys, having attended these classes before, just stand and watch the spectacle. Please don’t misunderstand, we can get birds to respond, but getting them to come within the effective distance of a smooth-bored flintlock is difficult.

On a number of occasions I have quoted Joseph Doddridge on the mandatory bird calling education of the youth of his era (Doddridge, 122-123), and pointed out several of Meshach Browning’s classic wild turkey hunts and his reliance on speaking “a few words in the turkey language..” (Browning, 122, 229 & 339). But Browning includes a different sort of turkey hunt in his narrative, one based on stealth, stalking and ambush:

“…one of the children came in and told me there was a flock of wild turkeys in the cornfield. I took my rifle, crept slyly round till I got the fence between them and myself; when lying down on the ground, I crawled to the fence, and there waited to make my selection. One of the turkeys had assumed the control of all the corn-shocks; and if, while he was picking an ear at one side of a shock, he heard another turkey on the other side, he would run round and drive him off. He would not allow any gobbler to pick at the same shock with himself.

“After he had driven three or four way, and they all seemed in dread of him, I called to him, in a low tone, ‘You are a fierce old tyrant, and it won’t last you long.’ This I knew would cause him to stand still, so that I could have a fair shot at him.

“When he heard my voice, he could not tell where it came from; and straightening himself up, he stood as still as he could, looking for the cause of the noise. I then fired at him, and over and over he went…” (Ibid, 163-164)

I view this passage as encouragement from the grave to try different approaches when the situation allows or when calling is not the best option—justification to “run and gun,” as neighbor Jeff says. All too often living historians get caught up in the overall romance of a given hunter hero’s tale. I have to constantly force myself to step back and delve deeper into a passage, to seek out the secrets hidden in the words.

Browning went on to say the gobbler “weighed twenty-six pounds; being the largest turkey I ever killed” (Ibid, 165). Dear reader, can you imagine telling such a story today? “…I took my rifle, crept slyly round…,” “…waited to make my selection…,” “…I [spoke] to him…,” and “…he stood as still…”—which part of a tale like that do you expect to see on a modern outdoor television show?

Last February, in the midst of a traditional hunting discussion, I was asked: “How many turkeys have you killed by calling them in, and how many by ambush?” Two of the participants, long-time veterans of the old ways, appeared flabbergasted. One said he believed the only way to kill a wild turkey was by calling it in. I responded by giving a thumbnail sketch of Browning’s story, and then I answered the question with “about fifty/fifty.”

When the circumstances of the forest are as they have been the last week or so, I prefer to set an ambush based on careful observation. With the hens on the nest, the toms tend to follow a daily routine along the same trails, across the same fields, and strutting in the same areas. The most the hens utter is a single hushed cluck or putt, thus a single, judicious drag on the wing bone is all I ever use, if that.

When the circumstances of the forest are as they have been the last week or so, I prefer to set an ambush based on careful observation. With the hens on the nest, the toms tend to follow a daily routine along the same trails, across the same fields, and strutting in the same areas. The most the hens utter is a single hushed cluck or putt, thus a single, judicious drag on the wing bone is all I ever use, if that.

The trick is to observe and learn and attempt to become a tenant of the forest. I have yet to be in a situation where I thought I could speak in a low tone to a gobbler, but the thought is always in the back of my mind, and when the time is right I intend to try. I have stopped deer and squirrels with a soft kissing sound, and once I froze a first-year six-point buck with a whispered “Hi there.” So for now, Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, will sit in ambush…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

One Response to Msko-waagosh Waited in Ambush…