A yellow birch tree popped. The bang rattled through the frigid bottomland like a hostile rifle shot. A blue jay started to scream a warning, but quit after the first penetrating “Jay!” It flitted to the top of a nearby maple. After a few seconds it swooped low over a snow-covered patch of sedge grass, then rose up and perched on the lowest branch of the noisy birch. It cocked its blue tufted head from side to side as if perplexed.

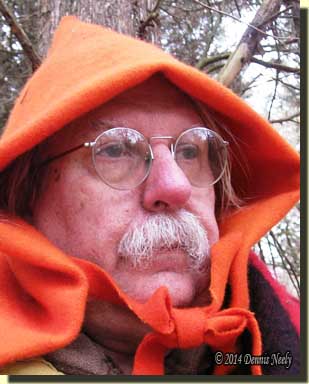

The light snow resumed. The Ojibwe-style wool hood limited the view to the north and to the south, more so than a pupil in the wilderness classroom was comfortable with. “The hood needs a different tie and it is still too deep,” the brass lead holder scribbled. With that revelation, I slipped the folded page into the buckskin envelope, along with the lead holder, and tucked the journal under the Northwest gun’s butt stock.

The light snow resumed. The Ojibwe-style wool hood limited the view to the north and to the south, more so than a pupil in the wilderness classroom was comfortable with. “The hood needs a different tie and it is still too deep,” the brass lead holder scribbled. With that revelation, I slipped the folded page into the buckskin envelope, along with the lead holder, and tucked the journal under the Northwest gun’s butt stock.

Round white balls tumbled into the folds of the crimson trade blanket as the snow pelted down. My eyes looked left, then right as I sat cross-legged on the mossy root ball of a scrub maple, just inside the west edge of the sedge grass haven. To the north, another tree cracked in the unseasonable cold. I realized I had lost track of the blue jay.

Five Canada geese winged high overhead, headed south in silent resolve. Picked clean by earlier flocks and browsing deer, few kernels remained in the cornfields. In the bottoms, sixty paces distant, the River Raisin lay frozen over. The constant current made crossing treacherous in the coldest of Januarys, promising certain death in mid-December.

“No geese, no Sandhill cranes, no song birds, no white-tailed deer—all that remains is snow, a lone blue jay and a foolish old woodsman braving December’s desolation,” the knife-sharpened lead scrawled.

About an hour later, the soft snap of a brittle twig announced the arrival of a roaming deer, a late-spring doe traveling without the wisdom of her mother. If the winter’s harsh start continued, I envisioned a grim future for this frail creature. She stopped not fifteen paces distant, pawed away the snow and nuzzled the ground. She lapped up two tongue’s worth of snow, but displayed no caution, no inclination for self-preservation. I assuaged the trepidation I felt for her by telling myself I was well hidden behind the walls of an impenetrable sedge grass fort. I knew better.

Not long after the doe disappeared in a cattail tangle, shivers overtook my being. Perhaps I was the frail tenant of the forest? I stretched my legs out from under the trade blanket and flexed my toes and ankles. I looked about, then rolled on my right hip to check for movement behind me. In due time, I scrambled to my feet. I fought the urge to shake the snow from the blanket, choosing instead to blend into the wintry glade as I stalked back to the high ground and the sanctity of a warm homestead.

The Challenge of ‘Measuring Up’

It has been my practice to frame an entire hunting season around a specific year in the last decade of the 18th-century. This helps focus attention on a narrow slice of history. My time traveling on this particular day landed me in 1796 in the Old Northwest Territory.

On two different occasions in the last week I have tried to articulate that point to surprised individuals who had no idea what traditional black powder hunting was all about. The motivation behind visiting the mid-1790s while on a deer or turkey hunt seems foreign to most people, especially modern hunters. Some shake their heads in disbelief while others ask subtle questions to satisfy their tweaked curiosity. Now as it happened, the discussion I had with both individuals evolved to the same assumption: “Well, you can’t do that in the winter, can you?”

The enthusiastic “Sure, why not” drew raised eyebrows. I fought off a pride-fillled snicker. You see, what we take for granted, most people cannot begin to fathom. Although they are polite enough not to ask, you can see in their eyes that they are asking themselves, “Why would a sane human being abandon modern creature comforts and subject himself to the physical punishment of the River Raisin’s wintry bottomlands? And how can he possibly come away feeling overjoyed, refreshed and satisfied?”

Experiencing the unique exhilaration associated with this glorious pastime knows no time limit and certainly very little restriction due to the elements. It’s sticky and humid as I pound the keyboard; the temperature passed eighty-degrees several hours ago, yet here I am re-living the sudden pop of yellow birch trees, watching a lone blue jay investigate and feeling concern for the scrawny fawn on that snowy December morning when the mercury struggled to hit double digits.

Experiencing the unique exhilaration associated with this glorious pastime knows no time limit and certainly very little restriction due to the elements. It’s sticky and humid as I pound the keyboard; the temperature passed eighty-degrees several hours ago, yet here I am re-living the sudden pop of yellow birch trees, watching a lone blue jay investigate and feeling concern for the scrawny fawn on that snowy December morning when the mercury struggled to hit double digits.

To be fair, for many time travelers the pursuit of living history focuses on creating an authentic historical impression that is shared with spectators. In museum settings or battle re-enactments, a guest’s satisfaction is the driving economic force and personal comfort is an important consideration—spring’s greening to fall’s vivid colors defines “the season.” There are exceptions, like the Nouvelle Annee re-enactment at Historic Fort Wayne, held the end of January in Fort Wayne, Indiana. But again, the slightest snowstorm or cold snap impacts attendance at such events.

Traditional black powder hunting is not a spectator sport. As I have said on a number of occasions, there are no bleachers, no gallery, no whispering commentators, no blimp droning overhead and the like. In most cases, the traditional woodsman’s time-traveling adventure is a solitary quest, a one-on-one, sometimes raw nerve encounter, between a linen-and-leather-clad gatherer and the creatures of the forest. Relishing the sheer challenge of measuring up to such an endeavor is worth the price of admission.

Working through the historical intricacies of perfecting a persona based on the lives of long dead hunter heroes can be a humbling and difficult task. The goal of any traditional hunt is to put meat on the family dining table, but adhering to the methodology described in the words of a long-forgotten narrative is just as important as having a proper load or picking the right time to take the shot.

For me, the satisfaction is in the hands-on doing and not necessarily in the taking of wild game—that is a bonus. Sharing the same physical discomfort and associated emotions with a kindred spirit, two-plus centuries removed, is a valued prize worth sacrificing for. I knew before I stalked the scrub maple in the sedge grass that the conditions of that historical simulation were not conducive to returning home with fresh venison. In an outdoor world dominated by trophy book critters and constant sensual bombardment from a host of commercial media sources, grasping this concept often eludes even the most astute observer nestled snug in the sanctity of a warm homestead.

Brave the elements for the prize is unmatched, be safe and may God bless you.