Elk moccasins left shallow prints in the sandy soil. Beyond the once majestic oak’s spear-like stump, a long-bearded tom turkey watched three hens peck their way to the east. The farthest hen perked up first, then the other two and finally the gobbler. The hens walked straight away. The tom hesitated and looked like he might fluff up in a show of dominance.

Then the young, grey-headed turkey on the right started to run. She took flight, flapping hard over the meadow. The wind from each downward beat sent a small wave rippling over the prairie grass. The gobbler folded his feathers tight, and like the two remaining hens, quickened his pace. One-by-one, the trio ducked into the safety of the waist-deep grass.

My moccasins marched onward. The wool leggins grew warm, the breechclout chaffed and I began to perspire as the sandy prints drew closer to the downed monarch. Standing beside the first fractured limb, the size of a stout man’s torso, I felt my face flush. A big sigh broke the morning calm. The inevitable reality of the forest lay sprawled before me. Then a long string of geese approached from the southwest, each uttering a single honk that echoed over the open rise like “Taps” played at Arlington.

My moccasins marched onward. The wool leggins grew warm, the breechclout chaffed and I began to perspire as the sandy prints drew closer to the downed monarch. Standing beside the first fractured limb, the size of a stout man’s torso, I felt my face flush. A big sigh broke the morning calm. The inevitable reality of the forest lay sprawled before me. Then a long string of geese approached from the southwest, each uttering a single honk that echoed over the open rise like “Taps” played at Arlington.

The trunk splintered apart, clearly rotted through. The south roots, severed just below the ground, flailed soil all about as the trunk pulled free—almost two centuries of surviving Mother Nature’s furies undone in an instant. No doubt, a lightning strike, a score of years ago, contributed to the tree’s demise. Chunks of punky heartwood littered the ground. Here and there, ants carried white larva to safety. Two distinct sets of fresh raccoon leavings added an irreverent insult.

I touched the bark as one touches the casket of a beloved grandmother. As I rested my hand, a wood tick crawled from under the linen shirt’s open cuff. I killed it before I bowed my head.

When I again looked up I glimpsed doe ears bobbing in the meadow. To my surprise, a tiny fawn burst from the grassy haven at the edge of the field, fifty or so paces to the west of where the turkeys entered. Its coat was cinnamon brown and the spots brilliant white. It bounded and pranced with youthful exuberance. A nervous doe followed four strides behind. With great effort, the upset mother ushered the youngster back into the security of the deep prairie grass.

“As a life leaves, another enters,” I whispered as I turned around and struck off to the east.

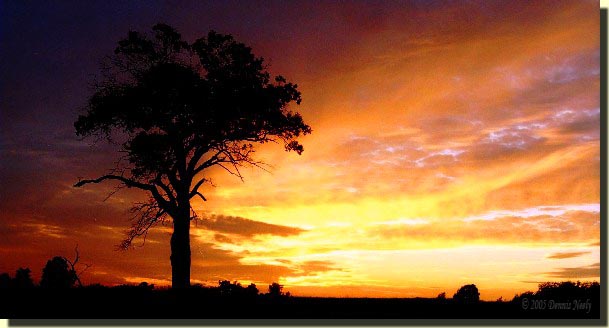

Mourning a Section Oak’s Passing

Since I was young, six or so, I have felt a connection to Nature, the land and especially to the trees that grow on the North-Forty. I think my Grandmother Sturgis instilled deep-seated feelings in me. We used to take walks in her backyard, which was “in town,” and my brother and I were required to name off the species of each tree on our way to her lush garden.

Since I was young, six or so, I have felt a connection to Nature, the land and especially to the trees that grow on the North-Forty. I think my Grandmother Sturgis instilled deep-seated feelings in me. We used to take walks in her backyard, which was “in town,” and my brother and I were required to name off the species of each tree on our way to her lush garden.

When I first discovered the “section oak,” as I call it, was down, I felt the same pangs as one does when a family member dies, then the mourning begins and eventually the healing. That tree, among many others, is, or was, a favorite of mine. I can’t begin to count the number of times I sat under that specific oak tree, sometimes hunting and sometimes for contemplation or reflection. And over the years, that section oak has acted as a guide to yesteryear. Somehow, passing under its spreading branches and whispering leaves ushered me over time’s threshold and back to my beloved 1790s.

One of my earliest recollections was my dad’s admonition: “Leave the section trees alone.” These are trees that happened to grow square on the surveyors’ section lines that created uniform townships under the Land Ordinance of 1785 (Bragdon, 86). A section is a mile square and a township is six sections to a side, or 36 sections—unless local politicians get to quibbling and the end result is a different number of sections, as in the case of Columbia Township. Human nature never changes.

There used to be four section trees—three red oaks and a white oak—along the north/south section line that starts where Hervey Parke drove a hickory stake in 1824. This tree was the sole survivor, and now it’s gone. Surveying manuals refer to such trees as “line trees,” but since I grew up with my dad calling them “section trees” that’s the term I use.

Section trees are the bane of farmers, especially today’s mechanized land tillers. Specialized sprayers with 100-foot articulated arms don’t maneuver well around them. As a youth, I remember seeing LeRoy Ehnis plowing that field with the shiny new red and white International 560 that replaced his faded Super M. As he rumbled westward through the oak’s shade the front tricycle wheels reared up like a great stallion. I thought Mr. Ehnis was going to flip over backwards, then the root severed releasing the plow point, averting a fatal disaster.

I remember three strands of barbed wire sticking out of the trunks of all four trees. Dad said it was left over from the 1930s, before the fences came down to make the little fields bigger and easier to plow. A few rusted strands still protrude from the great oak’s deep-furrowed bark.

I remember three strands of barbed wire sticking out of the trunks of all four trees. Dad said it was left over from the 1930s, before the fences came down to make the little fields bigger and easier to plow. A few rusted strands still protrude from the great oak’s deep-furrowed bark.

Ten years ago I returned to Michigan State University and enrolled in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric and American Cultures—leave it to a university to come up with a fancy name for “writing classes.” As a student in Professor Laura Julier’s “Writing Nature and the Nature of Writing,” I was required to have a semester project and I chose the section oak. I sat against that tree’s trunk, rain or shine, almost every day and recorded my “thoughts, feelings and reflections” in my journal. Mother died just before semester’s end, and I never completed the treatise. Professor Julier gave me an “incomplete.”

That tree became literary quicksand. As an avid living historian, curiosity got the best of me, and I ended up researching the original surveyor’s notes. Hervey Parke didn’t mention that tree, but he did mention others, none of which I was able to locate.

Next I felt compelled to “age” the tree. I used several methods, shy of a test boring, and with the help of a forester the tree was aged at 165 to 170 years old (this was ten years ago), not around for the 1824 survey, but about a foot thick for the 1880 re-survey.

Excitement grew as I realized the significance of that five year window: the acorn sprouted between 1835 and 1840. The Elder Calvin Harlow Swain traveled from New York State to the Michigan territory and founded the little settlement of Swainsville in 1832. Settlers came, and in 1836 the village was renamed Brooklyn. Perhaps that majestic red oak entered this world when Elder Swain and his family walked from Napoleon to his 40-acre parcel? And if not, it is quite possible its slender stem supported a dozen or so leaves when the village residents change the name?

In the early 1960s a three-tailed twister roared down that field. The section oaks lost some limbs and a lot of leaves, but they survived. I remember when lightning split the massive white oak, the next tree to the south. Kenny Creger sawed the tree up, Then Mr. Ehnis hired Ernest Hudson to remove the stump.

“…he heard my father used dynamite,” the late Jack Hudson said as he retold the story of how his dad got him out of bed at the crack of dawn to help “blow that stump.” Everyone laughed when Jack told how they used too much dynamite on the north root, blowing the stump over the road.

“…It took down the telephone wire and two strands of barbed wire on top of the fence…Doc Sirhal went through right underneath it. It took the windshield wipers, they were exposed at that time on the Cadillac he had…right off the windshield, and they went on over in the field, along with the stump…there wasn’t a scratch on his Cadillac…” (Jack Hudson interview, November 23, 2005)

Perhaps one of the saddest realizations is that mention of the section oak will soon fade from my 18th-century scribblings. That tree saw the founding of a town, the coming of settlers to the Michigan territory, the birth of a great state, westward expansion, the Civil War, World War I, World War II, and on and on and on.

The majority of the folks buried in Highland Cemetery came and went during that tree’s lifetime. One or two stapled barbed wire to its trunk, a few tilled the soil under its spreading branches, others harvested wild game and at least one of us ventured back to the 1790s while sharing the warm afternoon sun or a torrential rain that nourished its existence. What a witness to history…

Think about the tree you sit against, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to A Witness to History