A fox squirrel appeared on a white oak limb, to the left and a bit behind. It sat with its curled, bushy tail against the oak’s trunk and chattered, low and soft. The squirrel sounded contented. The morning light bathed the forest tenant. The pungent scent of drying leaves drifted down the hillside.

To the west, up over the ridge, another squirrel began the same rhythmic chant. No little birds sang that morning; none flitted about. The wild turkeys kept their tongues, too. Six black crows winged overhead, all silent, but two Sandhill cranes chortled off in the distance. It was late November, deep in the Old Northwest Territory, three ridges east of the River Raisin, in the Year of our Lord, 1792.

Some minutes later, the fox squirrel made its way down the tree and burrowed in burgundy-colored leaves. A deer coughed, up over the rise and down near the raspberry thicket. The exhilation sounded deep and heavy. Overtaken with a fit of exploration, the fox squirrel strew leaves all about, creating a great rustling. Above the unnecessary commotion, I heard a stout twig snap.

Arteries pulsed. Hips shifted to the right. My left leg pulled back slow, the knee rose up. The Northwest gun’s forestock rested on the buckskin leggin. My thumb fiddled with the firelock’s jaw screw. The deer coughed again, a few steps to the west, not all that far from where the main trail crossed over the rise.

Under a large, broad red cedar tree, just off the ridge crest, two front legs move, then stood still. I tried to peer through the cedar boughs, but the tangled mass was too thick. For an eternity I glanced back and forth from the forelegs to the earthen trail. Maybe fifteen minutes later a thick-necked body took two steps down the hillside. The deer’s head remained concealed behind the cedar tree, but there was little doubt it was a buck.

Two quick steps forward and a drop of the head confirmed my suspicions. The young buck displayed a proper set of first-year antlers with seven creamy-white tines. My right thumb pulled the trade gun’s English flint to attention as my finger worked the trigger to avoid the sear’s telltale click. My left arm eased the forestock up until that elbow planted firm into my left knee.

Three steps, maybe four, and the death messenger would embark on its fateful journey. As the turtle sight waited for the moment of truth, I whispered the hunter’s prayer: “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord.”

But then the buck’s head jerked up with a noticeable sense of concern. I heard three soft footfalls. The fox squirrel stopped pawing under the leaves, stood straight up, then with a flick of its tail it raced to the safety of the white oak’s trunk. A patch of brown fur moved through a small, shadowy opening in the underbrush. I suspected it was the coughing deer, but the fur’s closeness to the ground did not match that of a white-tailed deer.

The buck stared at the rise, lifted its right front leg, then stomped down with a hard thump. The fur stopped. It was then that I saw the black tip of the coyote’s nose, seventy paces distant. The bold beast continued to walk over the rise with the arrogance of a hungry predator. Moving real slow, the Northwest gun’s turtle sight found the coyote’s side of a little clearing around where the deer trail first breaks over the knoll. The remains of two dead fawns, found at the edge of the meadow’s prairie grass in early June, made the choice simple.

The buck stomped when the coyote was two strides onto the opening. The turtle sight grasped a dark spot just below the critter’s ear. The English flint lunged. Sparks flew. Priming flashed…

The buck stomped when the coyote was two strides onto the opening. The turtle sight grasped a dark spot just below the critter’s ear. The English flint lunged. Sparks flew. Priming flashed…

“Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

Yellow fire streaked from the muzzle. White smoke roiled. The trade gun’s thunder echoed through the forest. Debris flew straight up beyond where the coyote once stood. Tail down, the seven-pointer’s rump disappeared with a hint of white. Hooves over antlers he ran, until the sound of crashing leaves and snapping branches evaporated in the silence of the glade.

After the wiping stick thumped another death sphere firm against the gunpowder, I walked to the little clearing. I expected to find no hair, no blood trail. For me, hitting an apple-sized target at that distance would require more luck than skill. But I had to try; I had to take a chance at what lay beyond the young buck.

Different Places on the Path to Yesteryear

I had a quiet and inspiring conversation with a fellow traditional black powder hunter at Friendship this past week. We sat in the shade of a canvas fly on the Curly Gostomski Primitive Camp at the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association’s home grounds in southern Indiana. It was hot, humid and sweat soaked everyone’s linen and leather, which contributed to the eventual frustration that surfaced.

After catching up on family, the conversation turned to 18th-century loading methods for rifles, then to smoothbore loads, then to maintaining authenticity during a traditional hunt, and on to period-correct attire and accoutrements for specific historical re-enactments. As so often happens, the topic narrowed to primary documentation sources and the current interpretations of those research materials.

Another veteran traditional hunter wandered in and took a seat. He sat and listened, but when he entered the discussion, he did so with a “thread-counter’s attitude,” as my host later described it. As people walked about the camp area, this fellow dissected each one’s clothing and gear with a bit of an acid tongue. We both felt uncomfortable. Almost in unison, my host and I said, “We are all at different points on our journey.”

It was pretty cold under that fly for a couple of minutes. Then the subject changed to “people who helped us” on our own journeys and the lessons we learned from folks who were willing to share what they knew. The gent softened his tone when he started talking about his mentors, thirty-plus years ago. This led to a great sigh and an apology for being too critical of others.

As it turned out, he was dealing with a lot in his life, which is not offered as an excuse, only as an explanation of motivation. He came to Friendship hoping to step away from his own situation for a few days, but he couldn’t shut life’s concerns out of his head.

From time to time and in varying degrees, all traditional hunters face problems or circumstances that cloud and color their perspective on venturing back to yesteryear. That’s just part of the human condition, especially in these times. But we must all strive to rise above following the path of criticism and choose instead the path of sharing and teaching.

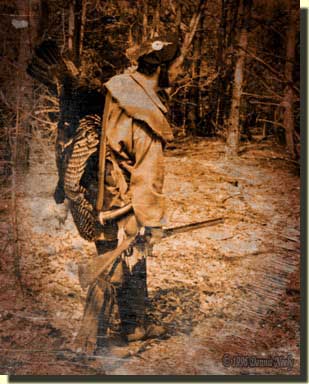

Yes, that is dark brown hair and a hodgepodge of not-so-period-correct garb, but a wild turkey still graced the family dinner table.

The next morning found me up the hill, standing in front of a large tarp filled with one man’s lifetime accumulation of living history gear. A close friend of his brought “his camp” to Friendship to sell. Facing the need for assisted living, his time traveling days had come to an end. Hand-forged knives and hawks, Hudson Bay blankets, cooking utensils, a gorgeous Great Coat, custom rifles and smoothbores, bags and horns lay on the blanket like bleached bison bones in the prairie sun.

Down the way, two streets over, an enthusiastic couple asked advice from a long-time vendor of living history goods. It was their first time at Friendship and they both had a shopping list. The vendor explained about being focused and basing purchases on historical documentation. He suggested other vendors to contact for specific items. One of the neighboring vendors went into her tent and brought out several outfits, explaining why she chose them and what to look for.

If you remember those days, you recall how foolish some of those first purchases were, and how far we missed the mark. Searching through my photo archives always brings a good laugh. But the traditional hunter’s goal is, and always has been, to engage in a portrayal that is better than yesterday’s, but not quite as good as tomorrow’s. Like the coyote’s unexpected visit, the pristine 18th-century moments we all seek still lie beyond the next rise.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.