Sunshine warmed the glade. Overhead, a gentle breeze rustled drying, brown, yellow and crimson leaves. To the south, a pair of blue jays swooped side-by-side from a tall red oak, then parted ways. A young doe wearing its first winter coat nuzzled ankle-deep leaves, searching for a missed acorn. She perked her head up when a plump fox squirrel dove from a shag-bark hickory, rolled once, then bounded off. As the squirrel spiraled up a stout white oak, the doe shook like a sopping-wet cur, then grounded her nose once again.

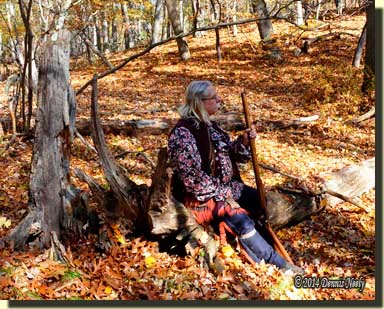

In the midst of that pleasant mid-October afternoon, the tribulations of backcountry life in the Year of our Lord, 1796, weighed heavy on a returned captive’s mind. The creatures of the forest went about their daily routines, giving little consideration to the woodsman sitting in the dappled sunlight at the butt-end of a barkless, hollow, fallen log. The woodland tenant sat motionless, observing the comings and goings while absorbed deep in thought.

In the midst of that pleasant mid-October afternoon, the tribulations of backcountry life in the Year of our Lord, 1796, weighed heavy on a returned captive’s mind. The creatures of the forest went about their daily routines, giving little consideration to the woodsman sitting in the dappled sunlight at the butt-end of a barkless, hollow, fallen log. The woodland tenant sat motionless, observing the comings and goings while absorbed deep in thought.

Some days the returned captive with the shoulder-length gray hair sat in front of the log facing east, and on others he sat watching the western knoll. The wind, the sun and the time of day determined which side he favored.

Then other days he might recline against a special white oak, over the rise and a bit to the southeast. Still others might find him sitting cross-legged on the shadow-side of a maple, the one with the storm-fallen oak top hugging its trunk, up the hill from the crossing trail he called “the isthmus.”

On those occasions, a Northwest gun lay across his lap. The death bees rested in tranquil resignation, too. Sometimes the brass lead-holder scampered across a folded page, and again, on others it might not. But always, with little warning, the reflective moment passed. The end was always the same. The returned captive regained his feet, woke the death messengers by checking the smoothbore’s prime and struck off in an unpredictable direction with renewed vigor in his step.

A Difficult Dimension to Add…

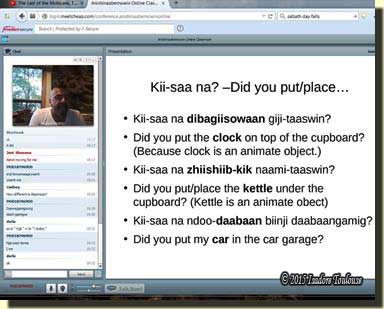

The creation of the returned native captive persona continues to be a taxing undertaking. I never considered all of the nuances of re-creating an individual with a cross-cultural upbringing. For example, last Tuesday night, a half hour into Isadore Toulouse’s weekly Online Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) webinar, Isadore asked:

“Kii-saa na zhiishiib-kik naami-taaswin?”

Thankfully the PowerPoint slide on the screen gave the answer to his question:

“Did you put/place the kettle under the cupboard?”

The slide demonstrated the correct way to ask in the Ojibwe language, “Did you put/place…” (Kii-saa na…) an animate object somewhere. In Anishinaabemowin (“the language”) objects are either animate or inanimate. In this case, a kettle is animate.

The slide demonstrated the correct way to ask in the Ojibwe language, “Did you put/place…” (Kii-saa na…) an animate object somewhere. In Anishinaabemowin (“the language”) objects are either animate or inanimate. In this case, a kettle is animate.

The next slide offered a couple of simple questions for inanimate objects, the first being:

“Kii-toon na emkwaan giji-doopwin?” or “Did you put/place the spoon on top of the table?”

I frantically typed notes as Isadore explained the differences in the language. On the one hand, I recognized “taaswin” as “cupboard,” “naami” as “under” and “giji” as “on top.” I felt a rush of enthusiasm as I learned “zhiishiib-kik” meant “kettle,” a word that would have been common in my alter ego’s 18th-century vocabulary, but in a matter of seconds all that elation came crashing down when I could not for the life of me recall “zhiishiib-kik.” As my father used to say when he thought I wasn’t paying attention, “In one ear and out the other.”

The Online Anishinaabemowin weekly classes taught by Isadore are free at 7 pm each Tuesday night during the school year. He speaks little of himself, but he is Odaawa and was raised speaking the language in his home. His “Auntie Shirley” pinch hits for him when a prior commitment keeps him from his beloved class.

Isadore exudes a deep passion for his heritage and his simple lessons are devoted to preserving the language by passing it on to others. From attendees’ comments and responses during the classes, it appears that most participants are Native American—Ojibwe, Odaawa or Potawatomi. They login from all over the world, some with a working knowledge of the language and some who wish to learn the language of their ancestors. And then there is a living historian who wishes to flesh out a new persona.

If an 18th-century captive spent a short time with his adoptive Ojibwe family, then knowing the language might not be necessary for an honest and truthful portrayal. But if an alter ego grew up as an adopted member of an Ojibwe family and returned to the settlements later in life that would not be the case—he or she would remember at least some of the language. And that pretext has driven my desire to gain a rudimentary vocabulary in Anishinaabemowin.

I’ve “attended” Isadore’s classes for over a year now, but alas, I can only recognize a handful of words or phrases. Some have made their way into my portrayal, but I find myself stumbling over the correct pronunciations, a reality that Isadore tries to alleviate by insisting that students repeat the words after he says them. Early on, my wife walked by the office and asked, “who are you talking to like that…”

For me, a deep sense of responsibility accompanies learning another culture’s language. As a living historian, I wish to engage in an authentic, 1790-era experience. But that simulation must also show respect for the Ojibwe people and their heritage. I think, at times, this inner need to re-create the language in a positive, period-correct sense is an obstacle to practicing what I have learned.

And this learning of the Ojibwe language has not been devoid of pristine moments. Early on, I felt desperation at just trying to understand what Isadore or Auntie Shirley said when either of them went into an “immersion lesson,” speaking entirely in Anishinaabemowin. The first time I didn’t understand a word, and the frustration drove me to the woods, which led to a few moments in time where I shared a feeling of kinship with Jonathan Alder:

“Despite my adoption, I was frequently low and not satisfied. Mrs. Martin and I were separated and the white man had left. I saw him only occasionally afterwards. There was no one living soul that I could talk with or understand except occasionally when I would meet a white prisoner. In this condition, I got very lonesome. I would set [sic] and think for hours remembering my home, my mother, and my two brothers. I was so full of sadness that I would be ready to burst out and cry. I made it a rule every day for a whole year at about three o’clock in the afternoon to go down to the river bottom to a certain walnut tree and sit down and cry for an hour or so until I could give full vent to my feelings. Then, I would get up and wipe up, and wash to prevent their knowing that I was in so great trouble. It is surprising to think how much relief that gave me. Notwithstanding my efforts to conceal my troubles, my Indian mother could see it. As soon as she could make me understand, she would frequently talk to me and tell me not to be troubled. I learned very fast, for the boys and girls took a great interest in my welfare and would try to amuse me and learn me to talk. I was a favorite with them” (Alder, 49-50)

Hopefully, after the first of the month I will have time to start making flashcards. Isadore also suggests labeling items around the house as an aid to learning. I expect to do that, especially applying labels to the trappings of this glorious pastime…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.