Wet leaves dampened forest sounds. Buffalo-hide moccasins uttered nary a whisper. Misty-gray sprinkles hushed that morning’s calm in an eerie, church cemetery fashion. The air smelled of wiggly worms, rotting deer leavings and wet-dog oak wood. The taste of smoked and salted venison jerk lingered on the tongue. It was the second day of May, in the Year of our Lord, 1793.

A solitary hen turkey clucked once at first light, high up in a slender red oak tree on the northeast corner of Fox Hill. The soft, scratchy “Arrkkk” ended quick and abrupt, leaving the impression the bird realized it had spoken in error. Nothing responded. Even the six Canada geese that winged over remained silent; the swish of their dark wings could not be heard, either.

An hour or so after day’s dawning, I scrambled to my feet, slung the bedroll over my shoulder and struck off to the north. That still-hunt skirted the nasty thicket, avoided the big scrape, then dropped into the valley filled with wild cherry saplings. A long pause before breaking over the saddle-rise allowed a single white-tailed deer, a yearling doe, to wander off to the east.

In time, the rolled-blanket, bound with a leather portage collar, found respite in a fork of a fallen oak top that still held most of its brown leaves. Once settled in to this new fortress, an index finger found the single radius wing bone in the bottom seam of the shot pouch. I dug it out, then rolled the cream-colored tube back and forth between my thumb and finger as I silently debated, “Do I call, or don’t I?”

A while later, off to the east and over the ridge, a hen clucked twice. A high-pitched gobble answered: “Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!” A deeper-toned gobble responded to the next sequence of four stern clucks.

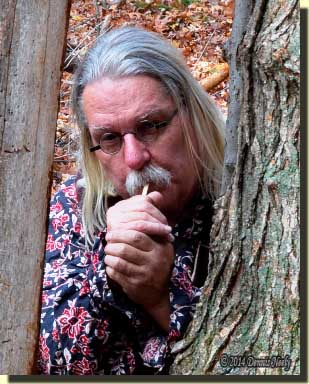

The wing bone still rested between my fingers, but little doubt remained as to what course to embark upon. With the bone to my lips, I kissed out four seductive, “come-hither” clucks. The sound hung about the treetop and lingered in the silence of the River Raisin’s bottom lands, which concerned me. “Perhaps I sucked too strong, clucked too loud, too bold,” I wondered. The hardwoods returned to their damp, eerie gloom, which deepened my misgivings.

The wing bone still rested between my fingers, but little doubt remained as to what course to embark upon. With the bone to my lips, I kissed out four seductive, “come-hither” clucks. The sound hung about the treetop and lingered in the silence of the River Raisin’s bottom lands, which concerned me. “Perhaps I sucked too strong, clucked too loud, too bold,” I wondered. The hardwoods returned to their damp, eerie gloom, which deepened my misgivings.

In due time my shoulders settled back against a limb’s rough bark. Song birds flitted about, but none spoke. Sandhill cranes winged over, then a string of eleven geese, all quiet. Another doe wandered by. A red-tailed hawk circled west. A lone fox squirrel spiraled down a shag-bark hickory, up on the little rise before the ridge crest. I fought the urge to move on.

A wild turkey’s head popped up by a leaning red oak. The gray pate disappeared. A dozen steps to the north, the head herky-jerked into sight. A fan opened, then turned about in a tight pirouette. When the spread tail feathers blocked the bird’s view, I pulled the Northwest gun to my armpit, raised my left knee and steadied the smooth-bored trade gun on that knee, as I had done so many times before.

The turkey took a few steps, fanned and danced, then paused as it waited for the mystery hen to show herself. Minutes piled up into a solid half hour. The short-bearded tom’s advance had not yet brought it to the shag-bark hickory, sixty-plus paces distant. After a double pirouette, the bird folded its tail, slicked down its feathers and marched in my direction. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” I prayed in silence.

Partway down the knoll’s gentle slope, the tom stopped beside a hollow sassafras tree. The mime’s ballet continued, first with a spin to the right, then another to the left, followed by a long pause in full display. Never once did that turkey gobble, spit or putt, at least not that I could hear.

By flexing the trigger as my thumb pulled the sharp English flint back, I eased the sear into the tumbler’s full-cock notch without the telltale click. In the middle of the next pirouette, the trade gun’s butt stock pressed into my right shoulder, but twenty paces separated the death bees from the moment of truth…

Two Single Wing Bone Turkey Calls

A glass-covered oak case sat on a small table situated in a dead space created by a jog in the cement block wall. A hand-lettered sign read: “Not for Sale. Display Only.”

On first glance, this display case’s contents seemed quite ordinary. It held a couple of fire steels, a folding knife, an antler-handled fork and knife set and a few other frontier artifacts. Then I did a double take, bent forward and tried to regain normal breathing. On the left side, just below center, an open tin spectacle case held two radius turkey wing bones and a bone-handled awl.

Tami and I were attending the 6th Annual Indian Art & Frontier Antiques Show at the Washtenaw Farm Council Fairgrounds, south and west of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Four inquiries later I found the owner, who was reluctant to make any definitive statements about the eyeglass case and/or its contents. I was not surprised. What could he say? He bought the rusted tin container from an antique dealer who said it might have come from a Native American family estate. There was simply no credible provenance. “The wing bones were probably turkey calls, but that’s a guess on my part,” he said.

Tami and I were attending the 6th Annual Indian Art & Frontier Antiques Show at the Washtenaw Farm Council Fairgrounds, south and west of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Four inquiries later I found the owner, who was reluctant to make any definitive statements about the eyeglass case and/or its contents. I was not surprised. What could he say? He bought the rusted tin container from an antique dealer who said it might have come from a Native American family estate. There was simply no credible provenance. “The wing bones were probably turkey calls, but that’s a guess on my part,” he said.

I did not handle the case or the bones; I treated them with great respect as one would any museum artifact. Holding a measuring tape close, the longer bone was about 4 1/2 inches and the smaller 3 7/8 inches. My impression was that the longer one came from a tom and the smaller from a hen—this assumption matches tom and hen radius bones in my possession. And from experience, I know that different length radius bones give different pitched tones.

Both wing bones were smooth from handling and appeared to be well used. The end of the longer bone opposite the flatter, “mouth-piece” end, had a clear cut line and both ends showed a ragged break, leaving the impression the ends were scored with a knife and the joint snapped off when the bone was fresh and green.

The owner thought the glass case was mid- to late-19th century, but a search found three similar eyeglass cases with the same style hinge and latch attributed to the late-18th century. One had a red-paint interior finish, and there were clear indications of red paint on the lid and back corner of this case. In addition, a stained and faded piece of olive-green, heavy-weave fabric covered the bottom of the tin. Did the owner want to muffle the rattling sound of the bones and awl?

And looking at the outside corners of the tin led one to think the eyeglass case was carried inside a soft-sided container—a shot pouch or perhaps a hunting coat’s pocket? Unfortunately, without some explanation from the original owner/user of this case, all of these questions, impressions or inferences amount to nothing more than speculation. No one can say for sure when the wing bones, awl and/or fabric were placed in the case or by whom or why.

What I can attest to is that I started using a single radius wing bone as a wild turkey call almost two decades ago. I switched from a box call when I discovered wing bones were dug up in the 1940s at the Eva archeological site in Tennessee. Workers were constructing the dam for Kentucky Lake at the time, and the excavations produced a number of wing bone yelper turkey calls, some single bones, some two bone calls, some radius/antler combinations and some radius/wood or cane calls.

The single bone calls caught my attention so I began experimenting in the wilderness classroom. I reasoned that after I mastered enticing turkeys with a single bone, I could move on to study the various combinations. As I said, I learned that different length bones give different tones, and for this reason, I sometimes carry two radius bones, one hen and one tom.

Other than the information about the Eva archeological site, I have never seen a single radius wing bone in a museum, illustration or mentioned in any narrative or journal. The exception to that statement is that Lewis Wetzel once made a turkey call from a “drum-stick bone” and “a piece of quill.” (Allman, 123) Yet despite the lack of credible provenance, you can imagine my elation with the discovery of the tin eyeglass case and its mysterious contents.

Oh, and you’re wondering about the short-bearded tom? He danced and fanned for another half hour. He never came closer, and he never uttered a sound. In the end, he folded his tail feathers and walked back over the ridge with a distinct air of disgust. Sometimes woodland caution is a potent antidote for love sickness.

A modern hunter with a diaphragm-style mouth call would have brought him in range, especially in range of a turkey-choked shotgun stoked with magnum plastic suppositories (I still think they are a fad and will never catch on). A hen decoy would have sealed the deal, too.

But that May morning’s time traveling adventure was set in 1793 and limited to the resources my hunter heroes had to work with—a single wing bone call, a downed oak top and a cylinder-bored trade gun. The actions required to set the Northwest gun down on my knee, pull out the call, put it to my mouth and draw a few love notes—well, the end result would have been the same as if I would have stood up and said, “Stay put, I’ll come to you…”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.