“A doe came through while you were gone,” Tami whispered as I sat cross-legged behind her trying to keep my shadow one with hers. A wool blanket, which broke up her shape, hung from her shoulders. A Chiefs-grade, smooth-bored trade gun lay across her buckskin dress. The air “smelled of fall,” as she so often says.

Reaching into the split pouch, I discovered the pencil’s lead end, the good one, broke during that morning’s still-hunt. Pulling the butcher knife, I scraped black dust from the blunt end that extended beyond the lead-holder’s tarnished brass jaws—all hidden on my lap, behind Tami’s blanket. In the distance, geese ke-honked as they rose from the River Raisin. Satisfied with the point, I slipped the knife into its leather sheath with care and began scribbling my wife’s words on a folded paper retrieved from the pouch…

“There’s six fox squirrels out. Two over there, two to the right and two up in the big oak with the broken branch,” my wife continued, indicating the directions with subtle movements of “The Silver Cross’” muzzle.

“There’s six fox squirrels out. Two over there, two to the right and two up in the big oak with the broken branch,” my wife continued, indicating the directions with subtle movements of “The Silver Cross’” muzzle.

“The doe was right there, maybe fifteen steps away. She was upwind. Had no idea I was here. Thought a buck might follow, but not yet,” she whispered with a hint of excitement. Twenty-seven geese flew overhead, a wedge and a line, gabbing as they swished in steady rhythm above the sunlit meadow that was to our backs.

We both kept our eyes on the shadow-laden, hardwood-covered hill that slopes gentle, then drops off steep until it washes out into the big swamp. The hill’s break was eighty paces distant, angling away from the heavy, furrowed trunk of a stately red-cedar tree that offered limited cover. On that fine November morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1798, Tami watched to the northwest, I to the northeast. I could see the meadow’s knoll, she the trail that led into the cedar grove.

“Jay! Jay! Jay! Jay! Jay!” Three blue jays hollered in unison as two fox squirrels chased in the brown leaves, then spiraled up an average oak. Not a minute later, a glimpse of white moved uphill from the sharp crest. Her trade gun’s walnut butt raised up a bit as she shifted her body to the right. A second flick of white trailed the first. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” I mouthed in silence.

The eight-point’s creamy tines were unmistakable. We had watched this buck chase does in the meadow several times in October. Without making a sound, Tami’s right thumb brought The Silver Cross’ black English flint to attention. The trade gun’s butt disappeared under the blanket folds. Head up, the buck advanced, the doe ten paces ahead and walking fast. My right eye peered around the trade blanket. I dared not move.

From where I sat, the doe disappeared in a clump of cedars and the antlers soon followed. I glimpsed only heads and ears and an occasional beam. Tami straightened her posture as The Silver Cross found its rightful place against her shoulder. An 18th-century moment of truth was at hand…

The Importance of Duplicating Results

“I can’t hold the gun up any longer,” Tami whispered. “I’ve got to let it down.”

“Do you still see the buck?”

“No, he followed the doe. They both walked away some time ago,” she said. Noticeable disappointment filled her voice. “I thought he would come back, but he hasn’t yet. He was just too far away for a good shot.”

We sat quiet for a while. The eight-point never came back. About a half-hour later, suspecting the morning activity was at an end, our whispers centered on that buck. Although I lost sight of him at the cedar clump, Tami’s vantage point allowed her to watch the two deer move beyond the cedars and walk off to the southwest, offering a quartering-away shot for a few seconds. As we talked in short, choppy sentences, she pointed out the four trees, selected at first light, which marked the outer boundary of her perceived effective distance.

Unlike re-enacting daily fort life or a significant frontier incident for spectators and onlookers, the objective of any history-based hunt is the taking of wild game—a living creature, a tenant of the forest, will die. Such business demands respectful, serious intent. To that end, the woodsman must know the extent of his or her own abilities, the limitations of the arm he or she chooses, and the constraints or influences imposed by the terrain itself in order to affect a quick, clean and humane harvest.

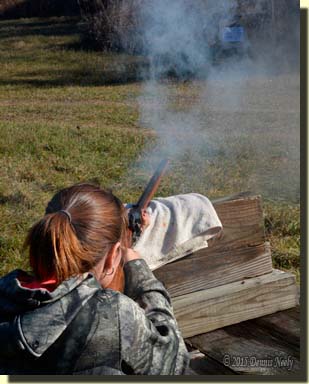

Addressing that second point, the living historian has an obligation to acquire and possess an acceptable level of proficiency with his or her chosen arm—in our case, 18th-century, smooth-bored, flintlock trade guns. Further, faced with the ultimate moment of truth in the wilderness setting, the traditional hunter must strive to live within the limitations dictated by a chosen technology of long ago. I simply cannot emphasize enough the importance of hands-on range practice, not just to gain a rudimentary skill level, but also to maintain and improve one’s prowess.

On that November deer hunt, my wife began her hunt by picking a series of trees to act as markers of the outer limits of her effective distance with The Silver Cross. If a buck walked on her side of a given cedar tree, she felt comfortable taking a shot; if the buck stood beyond that cedar she planned to let it walk.

In the last couple of years, I have spent extensive time learning how to load my Northwest gun in a “period-correct” manner using natural wadding. I have an orange file folder full of round ball targets and three armfuls of rolled brown-paper pattern-board tests. A separate file holds notes from those experiences, plus interviews with other long-time smoothbore shooters.

This research project has produced some interesting data and a lot of new friendships. In addition, my questions have sparked an exchange of information, good, bad and downright unsafe. It seems a week doesn’t go by that someone doesn’t send me an email or call with a lead or a link to a new source of smoothbore shooting information.

Of late, most of these sources have dealt with shooting the Long-Land Pattern Brown Bess. One writer, a history professor I believe, concluded that the arm was totally inaccurate after a dozen shots taken on the range by an individual who had never fired a flintlock prior to that shooting session.

Another lengthy treatise included graphs, distribution curves and data charts for a .715-inch round ball fired from a Brown Bess recorded in yardage increments out to 200 yards. In questioning this data, I found a number of living history web sites that linked to this gentleman’s report. It appears his “findings” are considered the authoritative source of Brown Bess ballistic information. From the opening introduction, the writer left the impression that these were actual fired-on-the-range test results based on specific loads.

I was ecstatic, convinced I could extrapolate information that would help me better understand “Old Turkey Feathers,” my 20-guage trade gun. I spent an entire evening breaking down the charts. The next night I searched for similar ballistic data for a 20-guage round ball. Late that evening I returned to a chart that compared trajectories for a number of muzzle velocities. I re-read the supporting statement. But my heart sank when I discovered the “Remember that this is theoretical data…” disclaimer. In my excitement I read right over that statement, as I’m sure others have. The entire “study” appears to be based on computer generated ballistic data.

And please don’t get me started on the multitude of YouTube videos produced by “experts” explaining how to shoot a smoothbore. I click off the minute the individual mentions this is a first time shooting experience, when the loading sequence explanation is filled with false “fur trade lore” or fails to follow accepted safe loading practices (like the fellow who fills his measure from an open can, sets the can on the bench and then fires from behind the loading bench), the target grouping is too good to be true, or it is clear the individual is not a regular smoothbore shooter. The exception is the gun-guys who show their “field tests” and state up front that they lack experience and expertise.

On the one hand, traditional black powder hunters base their living history simulations on the best available primary documentation—the printed word, period illustrations and existing artifacts. That is the gold standard in the hobby. But on the other, there seems to be a willingness to accept the shooting recommendations of anyone who can get their name in print or their face in front of a camera. This disconnect totally baffles me.

When it comes to the Northwest gun, I seek consistent, verifiable results that can be duplicated over and over, either with Old Turkey Feathers or a similar smooth-bored arm, using similar loads, under similar conditions. This is the essence of the wilderness classroom experience—hands-on laboratory experimentation in a somewhat controlled woodland environment.

When I go to the range, I have a plan for that session. In the case of the natural wadding tests, the plan is ongoing, carried out in small increments—corn leaves one evening, wide bladed grass another, then narrow-bladed grass, etc..

The purpose of these laboratory lessons is to attempt to produce sufficient data to draw conclusions, discover the limitations associated with natural-wadded loads and also to compare the accuracy attained with that of the best competitive loads. But the overriding question remains the same, “Can these results be duplicated?”

The other night I spoke with a long-time trade gun shooter and competitor. I asked pointed questions that some match shooters might think crossed the line into the secret side of paper punching—the area where the individual is reluctant to share his or her experience for fear of giving a potential foe a competitive advantage.

As is almost always the case, Ed shared his knowledge freely, both as it applies to the range and when engaged in the simple pursuit of wild game. Although he shoots a 28-guage trade gun, his expectations paralleled mine, as did his results with both round ball and bird shot. I found it fascinating that the groupings he got at the different distances matched mine, but he is not the only smoothbore shooter I have interviewed, and all report similar results and expectations.

Over the course of our conversation, he laid out a clear, easy-to-follow methodology, interspersed with the caveat: “This is what works in my gun…” His statements were based on thousands of rounds. No doubt, anyone with a 28-guage trade gun could use his loading process and duplicate his results, aside from peculiarities attributable to a specific muzzleloading smoothbore and personal marksmanship ability.

So, for the history professor, the re-enactor who has fired a mere handful of rounds and the YouTubers who just bought a Northwest trade gun, I raise the same questions: “Are the results you present based on extensive testing? Are the results consistent and verifiable? Can your results be duplicated over and over with a similar smooth-bored arm, using similar loads, under similar conditions?”

You see, as a traditional black powder hunter my 18th-century sojourn is not the same as re-enacting with powder loads; Old Turkey Feathers’ point of aim is not based on theoretical data; and the white-tailed buck standing forty-paces distant is not an assemblage of pixels on a screen. The business of this traditional woodsman is serious, yet undertaken in a respectful manner. If taken to its ultimate conclusion, a tenant of the forest will die.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

3 Responses to A Tenant of the Forest Will Die