Soupy mist rose from the watering hole. Frozen rain stiffened the sedge grass, encrusted red willow shoots and weighed down autumn olive branches. Ice grayed rigid cedar boughs. At a pause, a butterfly breath of a breeze crackled and snapped unseen silvery sculptures in the pre-dawn murk. Despite stepping toe first, each footfall crunched, leaving an unmistakable trail of white moccasin prints in the path’s short grass.

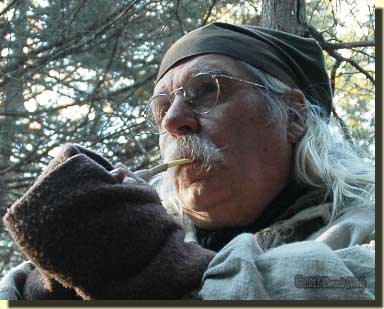

That morning’s course, in the Year of our Lord, 1795, proved short. The unsure footing, the muffled clash of buffalo hide and brittle prairie grass, and the ever-increasing drip of melting ice saw to that. Secure beneath the boughs of a broad cedar, one entwined with four looped grape vines, a once-captive woodsman pulled a wool blanket about his shoulders and settled back against the cedar’s keg-sized trunk.

That morning’s course, in the Year of our Lord, 1795, proved short. The unsure footing, the muffled clash of buffalo hide and brittle prairie grass, and the ever-increasing drip of melting ice saw to that. Secure beneath the boughs of a broad cedar, one entwined with four looped grape vines, a once-captive woodsman pulled a wool blanket about his shoulders and settled back against the cedar’s keg-sized trunk.

Flaming orange and lavender clouds marked the eastern horizon at first light. “Ark, ark…ark, ark, ark, ark,” a raspy hen turkey cried out. “Ark, ark…” a younger bird answered, followed by another.

“Caaw, caaw, caaw, caaw, caaw, caaw…” Two crows tried to incite a ruckus as they flew to the east. Others cawed to the south of Fox Hill; it sounded like three ranted off near the hidden lake. “Perhaps the enticement worked,” I mouthed, or maybe I just thought that?

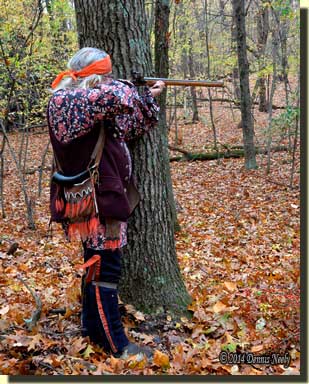

When the geese ke-honked at the lily-pad flats on the River Raisin, I pushed the frizzen up and checked the Northwest gun’s prime. The black granules moved about as I rocked the gun back and forth, and there was no indication of damp gunpowder.

“Swip-it! Swip-it!” a blue jay said, perched low on a dead cedar branch, not three trade-gun lengths to the north. I did not hear or see the blue-tufted sentinel arrive. My eyes looked straight ahead with a start, then eased to the left so as not to frighten the bird. The blue jay cocked its head and stared. I looked downhill, avoiding eye contact. In a matter of seconds, the forest guardian took flight, then swooped high up in a young oak tree, farther down the slope.

My eyes returned to the flintlock’s open pan. Without thinking, my hands rolled the trade gun to the right, ending with the usual abrupt jerk. The prime scattered on bare earth. I pulled the stopper from the horn that hung tight to my body under my right arm. With my thumb over the spout to control the flow, I up-ended the buffalo horn and sprinkled gun powder in the empty pan, taking care not to obstruct the touch hole. After replacing the horn’s stopper and setting the frizzen down, I again leaned back against the cedar.

“Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…” A crimson cardinal clung to an oak twig, a ways down the hill. The songster serenaded. More Canada geese ke-honked overhead. Four Sandhill cranes trailed close behind, sounding their joyous melody: ““Urrr-ggooou-aaa, Urrr-ggooou-aaa.”

A cock crowed at the second homestead to the east. By then, occasional melted drips had turned into a steady patter within the cedar trees that covered the upper third of the steep-sloped hill. The risk of damping the Northwest gun’s prime became too great. I rose to my feet, tucked the lock under my armpit and walked back into the open. Patches of blue dotted the thinning clouds…

Priming from the Horn

According to my journal entry, neither jake nor tom gobbled that late-April morning. Modest tree talk among the hens ended at fly down. The songbirds stepped to center stage on that unusual wild turkey hunt, along with the magnificence of a crystalline wilderness Paradise. A cold front moved through late the evening before, triggering a steady drizzle. Temperatures dropped below freezing. Ice greeted this humble hunter that morning. The intrigue of plunging into an unseasonable 18th-century storm’s aftermath overpowered reason and caution.

Early on in the creation of the returned white captive persona, Msko waagosh, I began leaving the greased lock cover home. I found no mention of a “cow’s knee,” as such covers are called, or similar protection in any of the Native captive narratives. I struggled, and sometimes still do, with keeping the priming dry in “Old Turkey Feathers,” my Northwest trade gun. But such tribulations are all a part of the learning process that accompanies any new persona.

The starkness of John Tanner’s Native captive narrative is a driving force for the Msko waagosh characterization. For me, engaging in a history-based hunt in colder weather has brought a new understanding of the reality of wilderness survival, an understanding that focuses on the basics, not the frills of living history.

After the blue jay startled me, I dumped Old Turkey Feathers’ precious prime more out of habit than conscious thought. I change my priming often during wet pursuits, but I surprised myself when I rolled the Northwest gun for no apparent reason. By then, re-priming from the bison horn was second nature, another return to basics habit.

About two years before the devastating EHD (epizootic hemorrhagic disease among the white-tailed deer) outbreak and the decision to create the new Native captive persona, my trading post hunter did away with carrying a priming horn containing 4Fg black powder. Instead, the historical me carried one powder granulation, using the powder from the horn to both load and prime Old Turkey Feathers.

I found no primary documentation for a late-18th-century woodsman in the Lower Great Lakes region supporting the use of a separate priming horn and/or finer powder. To the contrary, the inventory listings all show (or imply by not making any specific distinction) only one granulation of black powder existed at the trading posts.

I found no primary documentation for a late-18th-century woodsman in the Lower Great Lakes region supporting the use of a separate priming horn and/or finer powder. To the contrary, the inventory listings all show (or imply by not making any specific distinction) only one granulation of black powder existed at the trading posts.

Francois Victor Malhiot, a clerk for the North West Company, records a number of transactions in his 1804 ledger for “a double handful of powder” trading at one prime beaver pelt, or the equivalent (Malhiot, 218). Other trading clerks’ journals show a similar measure and value. None of these ledgers contains a reference or transaction related to finer gun powder intended for priming the firelock.

One unintended benefit of priming from the horn was the retention of powder in the pan. The lock on Old Turkey Feathers is a conglomeration of the best parts from the two previous locks. With the mainspring removed, parts might fly when the lock is shaken. That might not be a good testament to fitting and proper lock management, but…

At any rate, the fit between the frizzen heel and the pan and barrel is sloppy at best. FFFFg priming powder filtered through the gaps; on more than one occasion the flint struck the frizzen and showered sparks, but the pan did not ignite, because the prime was gone. Both 2Fg and 3Fg black powder granules are larger and will not sift out in the gap that exists on the lock’s pan. Lost priming powder is no longer an issue, plus the range of motion for carrying and using the smoothbore is now unlimited.

And finally, there is another concern that traditional black powder hunters must address, and that is the location of the horn on the body. The powder horn must be placed high enough so as not to move around when hunting, yet allow for quick easy loading using a measure. In addition, I have found that priming requires a bit more freedom of movement. In the end, the choice is left up to the individual, determined or dictated by experience in the wilderness classroom.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.