A distant crow cawed. Msko-waagosh shuffled sideways. A fox squirrel chattered. A crimson cardinal exclaimed, “Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…” A shiny, silver needle pierced the weathered canvas. The needle’s length grew short. The eye slipped through the weave. The thin cord followed with a tug from a thumb and forefinger.

“Aww, aww, aww, aww…” Three crows cawed above the cattails on the west bank of the River Raisin, or there abouts. The screams grew louder as the birds drew closer. The needle’s blunt point emerged from the fabric, above the horizontal cherry-sapling lashed to one of the wigwam’s hoop bents. The point dove back into the canvas, a few threads to the south of the first pass and under that horizontal rib. “Aww, aww, aww, aww…” A dozen screaming black demons swirled over the bottom slash, just over the hill, at the edge of the hardwoods.

Riled-up crows flew from all directions. “Aww, aww, aww, aww…” When the needle emerged, Msko-waagosh’s fingers pulled the cord through the eye, then he put the needle between his lips, so as not to lose it. “Aww, aww, aww, aww…” An owl flapped quick, flying low through the oaks, maples and hickories. The woodsman’s fingers pulled the cord tight, then started a slipknot. The gray streak swooped up, slowed, then disappeared in the thick green leaves of a young maple. “Aww, aww, aww, aww, aww, aww, aww, aww…”

An uncountable mass of black–winged assassins boiled in and out among the treetops, swarming with the fierceness of offended white-faced hornets. “AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW…” The forest offered no sound but the would-be combatants’ shrill hollering.

Elk moccasins shifted sideways. Brown, dry leaves rustled, but made no audible sound. “AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW, AWW…”

The shiny, silver needle again pierced the canvas, then passed from sight. The crows hushed, or so it seemed, despite the continued antagonism of a half dozen persistent birds. Crows lit in the treetops, then sat and waited. Some murmured amongst themselves, like young children shushed in church. The needle’s second loop complete, the cord pulled from the eye and the needle safe in his lips, Msko-waagosh tied another slipknot.

“Aww, aww, aww, aww…” On the southernmost edge of the flock, a lone crow cawed, took flight, then winged southeast. Others followed, some “awwing,” some not. Again the dusty moccasins stepped to the right, and the needle went about its task. Crows followed crows, and in the course of two minutes the screaming demons were but an exciting 1790s-era memory…

“…they built a wigwam…an Indian camp…”

The wigwam project has generated a fair amount of interest; unfortunately, I do not have sufficient knowledge or experience to answer all of the inquiries that fly through cyberspace. This endeavor is another laboratory assignment in the wilderness classroom, an ever-evolving lesson in progress, shared as it happens. Simply put, Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is another opportunity to explore a sense of kinship with long-dead, 18th-century hunter heroes.

The wigwam project has generated a fair amount of interest; unfortunately, I do not have sufficient knowledge or experience to answer all of the inquiries that fly through cyberspace. This endeavor is another laboratory assignment in the wilderness classroom, an ever-evolving lesson in progress, shared as it happens. Simply put, Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is another opportunity to explore a sense of kinship with long-dead, 18th-century hunter heroes.

By its very nature, a living historian’s hands-on education depends on trial and error experimentation, the results of which are measured, or perhaps interpreted, as successes and failures attained in the midst of a simulated slice of long ago. A part of this learning process is attempting to comprehend the sometimes feeble explanations penned on the yellowed pages of a grizzled old woodsman’s surviving journal. Another part is the faithful re-creation of what the student thinks those words mean, or were intended to convey.

Still another aspect is the constructive reflection after completion of the lesson plan, and of course, the formulation of future experiments designed to explore the myriad of unexpected questions that arise from what one thinks is a simple exercise in gleaning historical understanding. And in the end, the true test of any meaningful wilderness classroom lesson is the careful duplication of the experiment by others, undertaken in like circumstances, following the same process and producing like results.

In the early stages of his captivity, Jonathan Alder wrote:

“We crossed the Ohio about the middle of the afternoon and that evening one of the Indians went out and killed a deer. We went up to higher ground and selected a spot conveniently near to water and wood. It was always the Indians’ custom to burn dry wood (something that was generally easy to find) and also to camp near water. Next they built a wigwam, or what was called an Indian camp, and peeled bark and covered it and made it tolerably comfortable to what we had been accustomed to before…” (Alder, 38)

Unfortunately, Alder’s use of the word “next” is unclear. Did he mean that evening or the next day? Reading further, Alder states that two or three days hence his captors killed a large buffalo and set about making dried buffalo, or “jerk” as he called it, and that they stayed at this camp/shelter for “about two weeks.” He also notes, “we moved on, leaving our wigwam, never to see it again…” (Ibid, 39)

James Smith spoke of the Ottawa making “tents” using “flags,” cattail or rush mats, which he described as “…plaited and stitched together in a very artful manner…each mat is made fifteen feet long, and about five feet broad…” (Smith, 67)

He tells of one style of tent that sounds like a teepee, but in a later passage he also describes a shelter that resembles a “sugar loaf,” or the general wigwam shape:

“At night we lodged in our flag tents, which when erected, were nearly in the shape of a sugar loaf, and about fifteen feet in diameter at the ground…” (Ibid, 72)

Again, Smith is a little more specific in that the wigwam was constructed at the end of that day’s journey, utilizing existing covering material in the form of the flag, or cattail mats. Later, Smith reinforces the impression that these shelters were put up in a short span of time, and expands on the construction method used for a “sweat-house:”

“When we encamped, Tecaughretanego made himself a sweat-house; which he did by sticking a number of hoops in the ground, each hoop forming a semicircle—this he covered all round with blankets and skins…” (Ibid, 110)

Both Alder and John Tanner speak of using “tents,” and the context implies, but does not specifically state, a canvas tent/shelter. Tanner refers to many shelters as “lodges,” and tells of using a piece of painted cloth for a shelter. Early on in his narrative, Tanner describes using buffalo hides for what appears to be a temporary shelter used on a long journey, but he does not describe the structure’s physical make up—a wigwam, perhaps?

“We had thrown away our mats of Puk-kwi [woven cattails], the journey being too long to admit of carrying them. In bad weather we used to make a little lodge, and cover it with three or four fresh buffalo hides, and these being soon frozen, made a strong shelter from wind and snow. In calm weather, we commonly encamped with no other covering than our blankets…” (Tanner, 36)

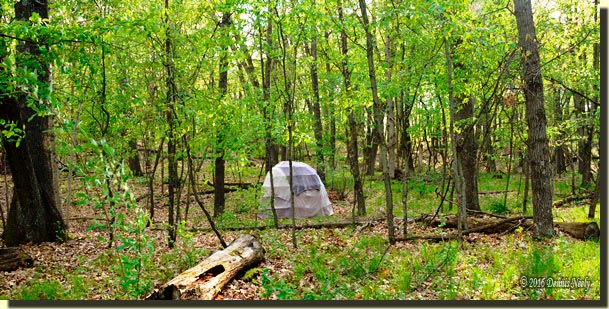

These written passages led me to construct a smaller wigwam, about nine feet in diameter instead of fifteen as Smith’s night lodging was, suitable for one or two hunters on a temporary basis. Now “temporary” for me means for an extended period of time, because I cannot move my hunting camp three or ten or forty miles down the River Raisin due to modern property rights issues. My 1796 adventures must take place within the boundaries of the North-Forty.

Likewise, skinning live trees for bark covering or spending hours weaving cattail mats is just not feasible, plus the cattails or rushes are not “in season” at this time, either. By default, canvas is the best alternative for the project, although such a covering material is more in keeping with a 19th-century wigwam.

And even then, I opted for cutting apart the seams of inexpensive, eight-ounce painter tarps instead of investing in high-quality canvas. The washed and dyed tarps will provide ample learning opportunities with an eye toward the future use of cattail mats and/or bark. After all, Msko-waagosh’s wigwam is but one more moccasin step down the unending path to yesteryear—and I look forward to sharing the next step…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.