Dense fog shrouded the doe trail. The air smelled thick, humid, and almost sweet, like drying corn. Water pattered down from tall oaks and short witch hazel bushes. Elk moccasins splashed the night before’s raindrops that clung to sparse, pale-green blades of prairie grass. The course progressed right, then uphill. Thread-bare, rust-colored silk ribbons hand-stitched to the leggin flaps told of trail-worn wool damped to the garters.

A dozen paces back an inadvertent brush against a red cedar tree’s drooping bough wet a ruffled shirt sleeve. The moisture felt warm. Despite the minor inconveniences, it was a magnificent day, deep in the Old Northwest Territory, three ridges east of the River Raisin, in the Year of our Lord, 1796.

The song birds made nary a twitter or peep. Thirty paces up the knoll, the doe path veered to the west, passing between two modest cedar trees with branch-tips a trade-gun-length-and-a-half apart. A perfect spider’s web, each strand lined with tiny silver beads, stretched across the path, extending from shoulders to ankles on a humble returned captive. A long pause failed to reveal the maker’s whereabouts. The elk moccasins circled the north tree, avoided another beside it, then returned to the gravel path.

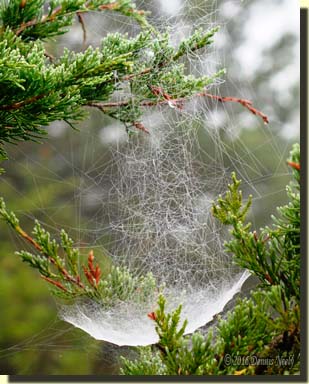

A dozen trees distant, a web of a different sort, spun at eye level in a wispy cedar bough, became the object of my concentration. This spider’s abode seemed to have two traps, a dense, silky weave that lay parallel to the ground and a hodgepodge of strands above. The clinging silvery pearls weighed down the former, distorting it into a dished shape. As I examined the contrivance from different angles, the morning’s soft light changed the shape; viewed from the north, the oddity looked similar to a schooner that I once saw from the bank of Lake Huron.

A dozen trees distant, a web of a different sort, spun at eye level in a wispy cedar bough, became the object of my concentration. This spider’s abode seemed to have two traps, a dense, silky weave that lay parallel to the ground and a hodgepodge of strands above. The clinging silvery pearls weighed down the former, distorting it into a dished shape. As I examined the contrivance from different angles, the morning’s soft light changed the shape; viewed from the north, the oddity looked similar to a schooner that I once saw from the bank of Lake Huron.

Lingering was not that sojourn’s intent, rather, soaked elk moccasins pressed on down the hill to the edge of the big swamp, arriving at the clump of cedar trees north of the narrows. The oaks on the south island appeared as misty gray shapes in the thick fog. Three crows flew from the thin cloud, but never uttered a sound. A blue jay’s rapid wing beats whooshed overhead. I did not move, so I expected no alarm.

At the doe trail’s gentle bend, three dead trees, all with the girth of a five-gallon rum keg, lay sprawled down the hill. The tops reached to the swamp’s sedge-grass edge. A clear path skirted around the obstructions. I followed that forest route, wishing to explore farther.

Forty paces distant, up near the mid-slope path, another red oak top clutched the steep hillside. Dark-brown, shriveled leaves still clung to the twigs; the exposed tear was damp, but clearly aged. I forgot about discovering this calamity in the fall of 1794. With cautious thought my elk moccasins crept along that earthen path, bent on scouting to the waterfall…

Discovering a Documented Compromise

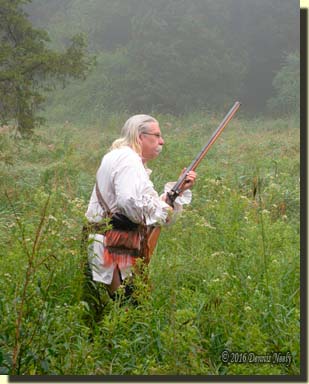

An overnight rainstorm and a brief break in this summer’s oppressing heat and humidity offered an opportunity for a 1790 scout. Stepping over time’s threshold took little effort; unbeknownst to me, my mind longed for a change of century. The ceremonial drenching was but a minor irritation.

Depending upon circumstance and my concern for personal safety, I rarely don hunter orange on these off-season jaunts, east of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory. I tend to describe such forays as “scouts,” rather than “still-hunts.” The technique for traversing the forest and fen is the same, but the intent is not to take game.

Further, I do not charge “Old Turkey Feathers” and often do not carry shot or round ball in my Odawa-style shot pouch. On several occasions this has proven to be a mistake, the most notable when a coyote stalked along the lower path as I rested cross-legged against a cedar tree just off of the south island. The coyote growled, then dashed uphill.

The historical me converted the beast to a wolf, in keeping with local settlement-period writings. But in a 21st-century sense, coyotes were in season on that day. Coyotes were, and are destroying our small game species, and of late have turned to running down the younger deer and fawns. I found four such kills in March alone. At any rate, I came away from that encounter disappointed that I missed an opportunity.

The concept of measured compromise dictates that a living historian must weigh, or measure, the impact of a 21st-century intrusion and apply a solution, or compromise, that minimizes the impact of that intrusion on an 18th-century time-traveling adventure. Thus, instead of wearing hunter orange and carrying a base hunting license, I chose to travel with an unloaded trade gun.

The concept of measured compromise dictates that a living historian must weigh, or measure, the impact of a 21st-century intrusion and apply a solution, or compromise, that minimizes the impact of that intrusion on an 18th-century time-traveling adventure. Thus, instead of wearing hunter orange and carrying a base hunting license, I chose to travel with an unloaded trade gun.

But up until the other night, carrying an unloaded smoothbore ran counter to all of my historical research—I wrote that inconsistency off to measured compromise. To the contrary, some of my hunter heroes stress the need to always keep ones arm loaded, which antagonizes that little nagging voice within a traditional hunter’s head that keeps saying, “That’s not period-correct!”

Then the other night I was in the midst of reading about the captivity of Isabella M’Coy when a passage overran my misgivings. With talk of Indians lurking near the new settlement at Epsom, New Hampshire, Isabella traveled to the garrison with her two dogs. When she found no one there, she returned to the family cabin. The next day, she, her husband and one of her son’s secured the homestead and headed for the garrison at Nottingham:

“…and all set off next morning, M’Coy and his son with their guns, though without ammunition, having fired away what they brought with them in hunting…”

“As they were traveling a little distance east of the place where the meeting house now stands, Mrs. M’Coy fell a little in the rear…Indians, three men and a boy, lay in ambush…but as his wife was passing them, they reached from the bushes, and took hold of her…Her husband, hearing her cries, turned, and was about coming to her relief; but he no sooner began to advance, than the Indians, expecting probably that he would fire upon them, began to raise their pieces, which she pushed one aside, and motioned to her friends to make their escape, knowing their guns were not loaded…This took place August 21, 1747.” (Calloway, 18)

“…her friends…” really? Anyway, after I got over the shock of that statement, which for me raises questions as the validity of this narrative being “primary” in nature, I started thinking about using up all of one’s ammunition hunting. John Tanner faced that prospect on more than one occasion, writing:

“When my balls were all expended, I drew my knife and killed one or two [elk on a frozen river] with it…” (Tanner, 65)

“…I went to hunt with only three balls in my pouch…” (105)

“…I had but seven balls left, but as there was no trader near, I could not at present get any more.” (115)

If you are a regular reader of my scribblings, you are aware that the latter passage is the basis for me carrying only seven balls when I hunt. But the end result of reading the account of the taking of Isabella M’Coy was to push me into rethinking and re-reading passages about the quantity of ammunition that 18th-century woodsmen carried. And for me, embarking on a scout with an unloaded Northwest trade gun no longer needs a dash of measured compromise, “…knowing their guns were not loaded…”

Strike out on a summer scout, be safe and may God bless you.

3 Responses to “…knowing their guns were not loaded…”