Distant clucks teased. Elk moccasins danced around the broken down top of a white ash tree. When the tree fell it bent earthward six or seven red cedar trees with trunks the size of a stout blacksmith’s upper arm. The open sky above this tragedy nurtured an abundance of autumn olive sprigs, most sporting half their summer foliage. It was, after all, the second week of November, in the Year of our Lord, 1796.

The windfall provided a fine vantage point to survey the long sloping hill that led into the cedar grove from the south. No bronze feathered bodies were evident on the ground. The still-hunt progressed with great care and caution. An earthen doe trail offered the easiest course. This trail leveled out well short of the old apple tree. Patches of turkey scratchings from three or four days prior, along with white-tipped droppings, covered the area.

The craggy old apple tree’s outstretched limbs sheltered an open grassless circle, perhaps twenty paces across. Progress slowed as the trail-worn, center-seam moccasins skirted the tree, intending instead to keep to the heavier cover. A ways beyond, two large cedar trees grew at the edge of a raspberry thicket. A similar sized cedar, bent over in an ice storm years before, angled out over the purple briars.

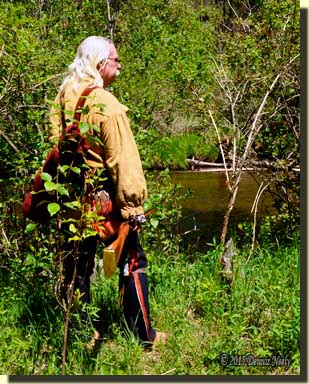

On another wild turkey hunt, a soft cluck from down the hill attracted Msko-waagosh’s attention. Sitting cross-legged on a bedroll, the woodsman turns, pressing the leggins into the leaves.

The wool bedroll, bound with a leather portage collar, eased into the space between the two cedars. After looking about, Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, knelt, then eased back onto the dark-red-colored cushion. A raspberry thorn tugged at the silk ribbon that bound the flap of his blue wool leggin. With its precious prime checked, the Northwest gun’s muzzle settled in the direction of the last cluck. Minutes ticked away as the woodsman scanned the forest floor for any sign of a roaming wild turkey.

Bare fingers explored the front of the deerskin shot pouch. The single wing-bone call pressed between lips damped with an intentional swipe of the tongue. Two breathy draws on the bone’s flatter end sent two soft clucks: “Ark, ark.”

“Ark, ark,” came the reply, uphill to the north, maybe fifty paces away, near a dozen waist-deep autumn olive bushes. Hips scooched to the left. The English flint rose to attention in silence; a gentle finger on the trigger depressed the sear bar as the hammer moved to full cock. The wool-clad left knee rose to meet the left elbow as the tarnished brass butt plate slipped against the returned white captive’s linen-covered shoulder. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” the woodsman whispered.

As the minutes ticked by, the turtle sight wavered a bit. Thoughts of lowering the Northwest gun erupted, but patience prevailed. The first wild turkey appeared in a scant opening, perhaps forty paces to the north. A second and a third followed, all pecking at the ground, turning side-to-side in search of an evening morsel. Several others flowed down the hill in what looked like a black wave. The lead bird sported a modest beard.

That tom angled to the southwest. With luck, his course might pass within the effective distance of “Old Turkey Feathers.” As the birds fed, none ventured closer. The turtle sight lurked over his back, the death bees anxious. Yet the moment of truth seemed a distant hope, fading with each herky-jerky step…

Honest Wear and Tear

My right hand clutched the trade gun; my left hand was empty as I walked from the cedar grove just before dark. The encounter proved noteworthy, bordering on a pristine 18th-century moment. But alas, a wild turkey would not be gracing the Thanksgiving dinner table.

Now and again a specific aspect of a time traveling adventure sticks with me. Most often a few words scribbled in haste keep coming to mind. On that fall turkey hunt, just a few days before the start of deer season, the notation of the curved thorn tugging at the leggin flap’s copper-colored silk ribbon came to the forefront of my recollections.

When the historical me first sat between those two cedar trees, he saw circular patches of honest wear and tear at the knees of both leggins; the cloth’s woven yarns no longer had any nap. The thorn and silk ribbons received mention on the journal page, the worn knees did not. I suppose in his subconscious thoughts, my alter ego equated the silk ribbon adornment as an indication of the Ojibwe influence, a clear sign the leggins were not intended for a common backwoods hunter of standard upbringing.

As I trudged back around the fallen white ash tree, I chuckled as I remembered Mary Brandenburg’s instructions on how to properly care for the hand-dyed silk ribbons I purchased from her at the Kalamazoo Living History Show. She spoke of not washing the article of clothing too many times, to be aware hot or humid weather might cause color bleeding, and she recommended dry-cleaning only for the garments. Mary’s advice was based on years of living history experience and was intended to maximize the life of the ribbon.

Not quite a year after sewing the leggins, the copper- and silver-colored ribbons still looked new and undamaged.

I appreciated her help and guidance, as I wished to make a pair of wool leggins that approached the quality and design of the original pair that belonged to Sir John Caldwell of the King’s Eighth Regiment of Foot, assigned to Fort Detroit. But from the start, I viewed the purchase of the ribbons in the same light as those bartered for from a 1790-era trading post, secured with the intent of using them to bind the flaps of a new pair of wool leggins destined for everyday use by a woodland hunter.

In November of 1796 those leggins had seen two years of hard traditional black powder hunting. In terms of 18th-century use, I estimate that compares to about five months of wilderness wanderings—my version of the “people years” versus “dog years” analogy.

The leggin’s wool fabric is just starting to show signs of wear, as noted on that wild turkey chase. The copper-colored ribbon on the leggin’s front flap is shredded and thread bare. The silver-gray ribbon on the back flap is intact, but soiled with a few thorn marks and a couple of places where the threads are starting to separate. That makes sense, because the front flap takes the brunt of the brush’s abuse while the back ribbon is somewhat protected.

The copper-colored ribbon binding on the left leggin (right) shows the wear and tear of everyday use, while the silver-gray ribbon on the right leggin (left) shows only minor distress.

After a morning hunt, the leggins are damped, if not soaked, to mid-calf at the least. My alter ego tries to take them off before crossing water of any depth, but that is not always possible. The Red Fox sits cross-legged, which grinds the ribbons into the ground, grass or leaves. Sedge grass, cattails and dry, brittle golden rod stems take a toll, too. Snow, ice and swamp muck accumulate on the flaps and who knows how many times thorns, twigs and thistles have grabbed, then released those ribbons.

But such wear and tear is consistent with the historical record. John Tanner was hunting for a trader in the dead of winter. He “started an elk” and pursued it all day…

“…What clothing I had on me, notwithstanding the extreme coldness of the weather, was drenched with sweat. It was not long after I turned towards home that I felt it stiffening about me. My leggins were of cloth, and were torn in pieces by running through the brush…” (Tanner, 64)

To be sure, Msko-waagosh’s wool leggins don’t look as “pretty and pristine” as they did when first sewn. Perhaps they are approaching the point where a “collector” like Sir John Caldwell might not consider them worthy of purchase, or a museum curator, two-plus centuries in the future, might record their collection number and relegate them to box on a shelf.

The Red Fox’s leggins look trail-worn and display a patina earned from the honest wear and tear of countless simple pursuits in the 1790s, east of the headwaters of the River Raisin. There is, after all, a toll for re-living history, for wishing to experience firsthand what it was like to live, hunt and survive in the Old Northwest Territory…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.