Snowflakes stuck to “Old Turkey Feathers’” barrel, yet the Northwest gun remained still. The small six-ponter stepped closer and closer, cross-wind, eighteen paces distant, on the mid-trail, down a steep slope. Large white flakes drifted earthward in the calm gray of first light. Crystalline beauty coated the crimson, four-point wool trade blanket, which smelled of wet sheep. My eyes squinted. My nose dripped. On that magnificent December morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1794, a first-year, unsuspecting white-tailed buck flirted with death, but passed unscathed.

A solitary blue jay flitted by. In due time, a fox squirrel with bristled-up hair materialized from a dried-leaf nest tucked high in a slender red oak that grew next to the trail the young buck chose. This creature spiraled out of sight. My eyes glanced about as I looked for another deer, then returned to the oak.

A solitary blue jay flitted by. In due time, a fox squirrel with bristled-up hair materialized from a dried-leaf nest tucked high in a slender red oak that grew next to the trail the young buck chose. This creature spiraled out of sight. My eyes glanced about as I looked for another deer, then returned to the oak.

The squirrel reappeared on the tree’s left main branch, scurrying upward. The limbs became thinner. With a mighty leap that flexed a wispy twig and a flash of tawny underbelly, the fox squirrel jumped to a bigger red oak. It stayed atop the branches, sending snow flying. At a bend in a thigh-sized limb, it seemed to slip. Its hind end and bushy tail scooted south. Its pace slowed before vanishing from sight once again.

No deer moved, but neither did the fox squirrel. Snow filtered through the barren branches overhead in a soul-soothing shower. A large flake came to rest on the Northwest gun’s turtle sight. An eternity later, the squirrel circled ‘round the trunk, well up and just below the first main limbs. It hung head down, looked to the east, then west, and barked thrice. The scratch of its little claws filled the forest’s silence as it edged lower, then hung again.

Satisfied no present danger existed, the fox squirrel jumped into the fresh, deep snow as a sleek otter dives beneath a tranquil beaver pond’s glassy surface. It emerged in an explosion of white, bounded twice then burrowed like a mole in soft earth. Not more than ten paces distant, the squirrel burst forth and sat upright with a constant flicking of its bushy tail and a steady chatter that all could hear.

The squirrel bent forward. Leaf-parts flew and settled on the snow behind it. It turned east and dug again, then burrowed ahead a foot or so and began searching anew. A half-dozen times the fox squirrel dove into the snow, dug in earnest, then moved on. All motion stopped. The bushy tail twitched twice, then the squirrel sat upright with an un-capped acorn clutched between its front paws. It chattered again, loud and long, then started cutting on the nut that rolled over and over in its tiny claws.

In time, the search resumed. The screech of a distant red-tailed hawk put an end to the diving, burrowing and excavating. The squirrel ran to the nest oak with steady bounds. It spiraled up that trunk and disappeared, only to reappear on the thinner branches that led to the dried-leaf nest…

Similarities between then and now

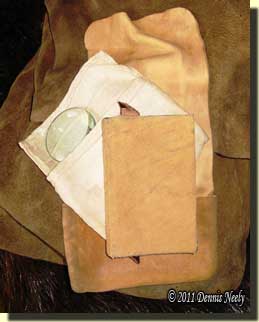

The historical me that portrays a backwoods hunter for a small trader’s post near the headwaters of the River Raisin tucks a copy of the New Testament in his deerskin hunting bag. In the early years I made a hand-sewn linen envelope for this Bible. One day I took an unplanned swim in the swamp. The hunting bag got wet, but the contents didn’t. That wilderness classroom lesson resulted in a new perspective for how I stow valuable accoutrements.

Not long after, I stitched up a deerskin envelope for the New Testament and the first linen cover. When I traded for a burning glass, the lens fit in the cloth pouch, and the outer deerskin pouch provided additional protection. I’ve carried the New Testament and Psalms that way ever since.

Not long after, I stitched up a deerskin envelope for the New Testament and the first linen cover. When I traded for a burning glass, the lens fit in the cloth pouch, and the outer deerskin pouch provided additional protection. I’ve carried the New Testament and Psalms that way ever since.

I don’t pull the New Testament out and read from it as much as I should, but on that morning I did, despite the falling snow. I held the hand-sized book close so melting snow would not damp the pages. As I sat watching the fox squirrel seek that day’s sustenance, my thoughts turned to matters other than deer hunting.

I keep a cutting of brown silk ribbon marking “The Sermon on the Mount” in Matthew’s Gospel. My being, both modern and historical, is drawn to what used to be called “the lilies of the field” passage. The newer translation lacks the rhythmic eloquence of the old, at least for me. My late wife, Mary, loved those brief verses, and there is an 18th-century connection, too.

This past weekend, the “lilies of the field” passage was the Gospel reading at church. The message lingered in the back recesses of my mind. I remembered that December morning and the fox squirrel burrowing in the snow—funny how a living historian’s mind associates 21st-century happenstances with events of a bygone era. This passage is several verses long, so for brevity I will touch on the basics as they apply to my hunter heroes:

“Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment?” (New Testament, Matt: 6, 25)

“…Consider the lilies of the field, and how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: And yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these…” (Ibid, 28 – 29)

“…But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you. Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” (Ibid, 33 – 34)

A young George Nelson signed on as a fur trading clerk for the XY Company. Nelson had never been away from home, and as a result, his journal contains some poignant passages. I depend on his writings, along with those of several other traders and clerks, for guidance with my trading post hunter persona.

“We left all behind, on Stages, covered from the weather, & entered the woods on the East Side of Riviere des Sauteux, taking our Course for the Wees-kon-sin, thro’ a thick forest. We took a slight breakefast & left the remainder of our provisions behind, observing the precept in this perhaps solitary instance ‘every day will provide for itself.’ Our Guides Son, a lad about 20 was out a hunting; and as he did not join us, his mother took an axe & beat for a long time upon a large hollow stump. The next morning he rejoined us. I do not now remember what it was that kept him back. We had proceeded but a short distance when saw a Deer bounding across the woods before us. A Shot or two deprived him of his existence, tho’ flying as it were, & provided for ours. I may say it was not yet quite dead before some of our party had eaten it—so expeditions were we!” (Nelson, 126)

On the returned white captive side, James Smith was 18 years old when he was taken captive and adopted in 1755. Smith had a Bible, and references it on several occasions in his narrative. At one point, he loaned his copy to Arthur Campbell, an adopted captive residing in a Wyandot village on Lake Erie. Smith wrote:

“During his stay at Sunyendeand he borrowed my Bible, and made some pertinent remarks on what he had read. One passage was where it is said, ‘It is good for man that he bear the yoke in his youth.’ He said we ought to be resigned to the will of Provikence [sic], as we were now bearing the yoke, in our youth. (Smith, 64)

Smith went on to reference the “take therefore no thought for the morrow” passage:

“…we had either green corn or venison, and sometimes both—which was comparatively, high living. When we could have plenty of green corn, or roasting-ears, the hunters became lazy, and spent their time as already mentioned, in singing and dancing &c. They appeared to be fulfilling the scriptures beyond those who profess to believe them, in that of taking no thought for to-morrow; and also in living in love, peace and friendship together, without disputes. In this respect, they shame those who profess Christianity.” (Ibid, 65)

As the old adage says, “The more times change, the more they stay the same.”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.