A wheezy snort foretold of a deer’s approach. Although hushed, the distant cough-like blow traveled from the north island, up the rise and into the humble cluster of thorny bushes that grew tight around a tall oak tree. For any 18th-century woodsman, sitting with his back to that trunk, such a sound was unmistakable; it was mid-December, in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

Ten minutes passed. A patch of brown hair rippled in the slim space between two trees that towered at the edge of the big swamp. A grey squirrel hopped along one of the upper branches. A blue jay perched in a nearby wild apple tree. A doe stepped from behind one of the oaks–on the trail from the south island. There was ample time for the doe to travel from the north island to the south, but that scenario seemed a bit farfetched.

Two smaller does followed the first. The trio plodded beyond the great oak, then angled up the slope and disappeared to the southwest. Two gentle splashes off the north island confirmed the hunter’s suspicion; multiple deer were crossing the big swamp. The air was calm and crisp. Measured breaths drifted through the tiny branches that shielded the skimpy fortress. A hint of tannic acidity perfumed the glade, mixed with the scent of fresh turned earth from the cleared ground beneath the woodsman’s wool bed roll.

A button buck and a pencil-necked doe walked in front of the two tall oaks. They browsed and nibbled their way around the near side of the great oak. The little doe pawed for acorns twice. The button buck pressed on. He paused at the upper trail, looked back and uttered an ornery bleat. His sibling glanced up, then bounded uphill. They, too, vanished at the ridge’s crest.

“Chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dee,” a solitary chickadee sang as it inspected a red berry clinging to the thorny stem of a barberry. “Chic, a-dee, dee, dee, dee…” With no deer in sight, the little songster provided a pleasant diversion.

The bird flitted to a different bush. A deer’s hind leg moved, first seen over the chickadee’s back, to the north at the swamp’s cut bank. That deer lingered in the solemnity and shadows of a clump of cedar trees for longer than expected. The hind leg stepped out of sight, then a foreleg came into view, placed slow and with surety.

The bird flitted to a different bush. A deer’s hind leg moved, first seen over the chickadee’s back, to the north at the swamp’s cut bank. That deer lingered in the solemnity and shadows of a clump of cedar trees for longer than expected. The hind leg stepped out of sight, then a foreleg came into view, placed slow and with surety.

Some minutes later, a splash and a low, guttural grunt close to the clustered poplar trees at the north island’s northwest corner left little doubt that a buck of some size was making his way to the tangled swamp’s west bank. The big doe turned about and started uphill, angling away at a brisk walk. She crossed the second trail, then the mid-hill trail, rustling leaves as she went. Four strides above that trail, she stopped quick and looked downhill. Then a patch of side hair appeared in the cedars the doe just left.

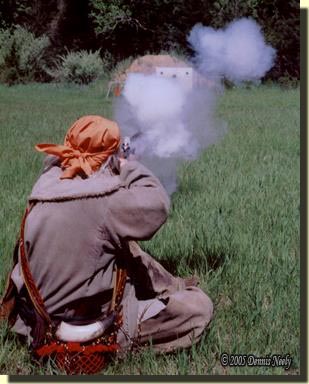

“A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord.” The prayer’s thin vapor drifted into a barberry bush. The right index finger worked the trigger as the thumb eased the hammer back, done so many times by feel, until the sear slipped in the tumbler’s full-cock notch, all without a sound. When the doe peered uphill, the Northwest gun’s tarnished brass butt plate crept to the woodsman’s linen-clad shoulder.

With a small bounce, the doe continued to the north. The hair vanished about the time she glanced at the cedar clump. The turtle sight waited where she had emerged, but the handsome buck, at least three winters old, did not oblige. Instead, slow splashes in the creek told of a deer stalking north; he appeared a dozen paces out into the sedge grass, walking parallel to the doe, well beyond the Northwest gun’s effective distance…

Thinking Beyond One’s Effective Distance

Taking a high-percentage shot, well within the performance capabilities of not only the black powder arm but also the time traveler’s abilities, is the ultimate goal of every traditional black powder hunter. This is the responsibility a woodsman must accept, the moral code a tenant of the forest must live by.

Yet, experienced living historians know the 18th-century writings of a favorite hunter hero sometimes contain shots that were too risky by today’s ethical standards or not allowed by the hunting statutes. For example, here in Michigan taking a wild turkey with a round ball is prohibited—but Meshach Browning did it. Likewise, John Tanner would not have released a death messenger to pursue that odd-antlered buck, because he would have shot the first mature doe as soon as she stepped from behind the two tall oaks.

All of the deer that wandered over time’s threshold that morning were within the Northwest gun’s effective distance, save that seven-pointer with the damaged left beam. As moderns, as traditional black powder hunters and as living historians we must respect the game we pursue and do our utmost to effect a clean and humane kill. I harp on that a lot, which is why the principle of determining one’s “effective distance” weaves its way into so many of my missives.

Mixed into the backstory for John Tanner’s courtship of Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa, Red Sky of the Morning, in “Plucking a Few Choice Words” was a story about Tanner shooting at a mark. His prowess with his firelock redeemed the family’s gaming loses:

“We staked every thing we could command. They were loath to engage us, but could not decently decline. We fixed a mark at a distance of one hundred yards, and I shot first, placing my ball nearly in the center. Not one of either party came near me; of course I won, and we thus regained the greater part of what we had lost during the winter.” (Tanner, 100)

Tanner doesn’t say whether he was shooting a rifle or a smoothbore. At a different time, under different circumstances in his narrative, he talks about owning a rifle and how his adopted brother damaged the barrel out of spite. However, most of his hunting exploits involve a smoothbore, and I strongly suspect he was shooting his smooth-bored trade gun that day.

Thus, for me, the sentence, “We fixed a mark at a distance of one hundred yards, and I shot first, placing my ball nearly in the center,” establishes the personal marksmanship level a returned white captive persona should strive for. That said, it is important to note that the others “…were loath to engage us…,” and after the smoke cleared, “Not one of either party came near me…” One might make the assumption that Tanner knew his own ability, and the others in the party knew theirs, as well. Nonetheless, the gauntlet lies in front of my moccasins.

While reflecting upon this lofty goal, I realized the bulk of my range practice centers on maintaining personal proficiency within the long-established effective distance for “Old Turkey Feathers.” I have taken longer shots at woodswalks or during the Fort Greeneville Match at Friendship. An animal’s life is not in the balance in such situations.

While reflecting upon this lofty goal, I realized the bulk of my range practice centers on maintaining personal proficiency within the long-established effective distance for “Old Turkey Feathers.” I have taken longer shots at woodswalks or during the Fort Greeneville Match at Friendship. An animal’s life is not in the balance in such situations.

I also came to the realization that I rarely take a shot over 50 yards on the range anymore. I follow that practice while immersed in a simple pursuit, too. I don’t feel I need to reach out to 80 paces like I once did. However, after ruminating on the aforementioned passage, these practices have to change. Hitting the mark at 100 yards is the challenge Tanner presents.

Oh, I have a good idea where Old Turkey Feathers shoots at that distance, based on almost four decades of shooting the same gun. Twenty-five years ago (can it be that long?) I helped a black powder shooter sight in a new .54-caliber Hawken rifle he had just completed. The sights needed little adjustment for point-of-aim to match point-of-impact at 50 yards. About twenty shots later he found a suitable load that he was satisfied with.

On a whim, he took an empty gallon milk jug from the back of his pickup, hiked to the watering hole and filled it up. He continued on down range and set the jug in a hollow in the hillside, in front of a thick clump of cedar trees. He had a long stride, and said he counted 110 paces on the way back. The distance was close to 120 yards.

We loaded up. If I recall, his first shot was low, but with the addition of some “Michigan windage” his next three hit, then a miss. My first few shots missed, but not by much. Then I hit the jug high and rolled it back against a cedar tree. After his final hit, he said he had to try Old Turkey Feathers. I think he fired ten shots, and after the first few, he tickled the jug a time or too. We never hit it again, but we came real close. We quit shooting when it was so dark we couldn’t see the jug.

I forgot how much fun we had that night, and it was all unplanned. I thought about that session when I worked on the story of Tanner’s courtship. I know what skills I need to work on. After 25 years, the eyes will be a factor, too, but that makes little difference. Perhaps I will fare no better than Tanner’s competitors, and that’s okay, too. For me, the thrill is in sharing a sense of kinship with John Tanner and my other hunter heroes.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.