Half-leafed treetops rustled overhead. Day’s first gray glimmers half-lit the winding wagon trail. Elk moccasins whispered beside the left rut. Around the bend, the predawn stalk struck off on a well-used doe trail that angled northwest. A gentle breeze, perfumed with a hint of stagnant swamp water, kept the mosquitoes distant. Such was the start of the fifth day of May in the Year of our Lord, 1798.

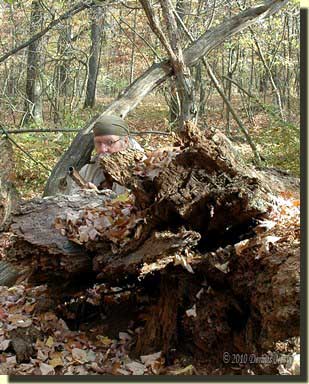

Up the rise, a stately red oak once stood. Two decades before a hunter for Samuel the Trader camped beneath that forest sentinel. One-by-one the major branches broke from the tree’s hollow trunk. In early summer the year before, a hefty windstorm pushed the trunk to the south. The roots of that ancient monarch were rotted away and offered no resistance. In the cycle of life, it was time. But the hulk lived on, creating a fortification suitable for deceiving a wild turkey gobbler.

Up the rise, a stately red oak once stood. Two decades before a hunter for Samuel the Trader camped beneath that forest sentinel. One-by-one the major branches broke from the tree’s hollow trunk. In early summer the year before, a hefty windstorm pushed the trunk to the south. The roots of that ancient monarch were rotted away and offered no resistance. In the cycle of life, it was time. But the hulk lived on, creating a fortification suitable for deceiving a wild turkey gobbler.

“Arkk.” To the west, in the midst of the River Raisin’s bottomland, a hen uttered a soft, gravely cluck. Crows began to caw with great fervor, and if there was any response or further discourse, it was never heard. A tom, young or old, gave no answer from the roost. Sparrows chirped, cardinals “whit-tsued” and blue jays screamed now and again, but nary a gobble.

A solid half hour after full light, the wing bone call offered a solitary “Arrk,” soft, yet crisp in tone. One cluck seemed so insufficient, but lack of vocalization by the wild turkeys demanded restraint by their imitator.

Then the sun dimmed as thin, gray clouds gave way to their denser cousins. An eerie quiet settled over the forest as if foretelling what was to come. The heavens grew darker. The songbirds sought perches low in the trees. The breeze cooled, then chilled as a fine mist dispersed amongst the hardwoods. The Northwest gun slipped back so the lock rested under the woodsman’s arm, tight to the body. Damp fingers folded the linen shirt’s collar up and snugged the silk neck scarf.

Large droplets started pitter-pattering all about like the overture to an unwanted symphony. The rain’s intensity made seeing the young trees in the river bottom impossible. The first movement crescendoed into a deafening downpour. Water pooled in cupped leaves, flowed down the west side of the tree trunks and painted an ice-like shimmer to the forest floor.

To make for the presumed comfort of the hunting camp meant the certain wetting of the smoothbore’s precious black powder. Protecting the trade gun’s charge outweighed personal comfort. The barrel remained pointed downward. Drips merged, then tiny puddles gained volume and momentum as they raced toward the turtle sight.

The same patience that waited on the gobblers and hens, now applied to the spring rain. To the west, a narrow band of light grew taller with each sopping minute. The torrent slowed, and over the next twenty minutes, the storm eased at the same rate it intensified. The ebbing drizzle brought with it a different sound, one of subtle splishes and splashes. Gray clouds replaced the dark ones, then streaks of sunlight speared through the gloom. When the mist ceased, the wing bone call again offered a solitary “Arrk,” soft, yet crisp in tone…

Unbreeching a Trade Gun Barrel

Sitting through that sudden spring downpour was a gamble. A careful walk back to the station camp’s tent risked an almost certain wetting of the priming powder and/or the main charge. Sitting tight and protecting the Northwest gun’s lock increased the probability of avoiding that calamity. Of course, the absence of lightning weighed heavy on that choice. Yet, in either case, this humble woodsman knew he was going to get wet.

Now and again, a hunter hero scribbles a few words about a wet load. Meshach Browning wrote about shooting a buck deer and pursuing him at a rapid pace:

“…But in running through the bushes, some snow having fallen on the lock of my gun, wet the powder, and it would not fire…” (Browning, 29)

Likewise, Alexander Henry found himself lost in the snowy wilderness. In his attempt to return to Lake Michigan, Henry happened upon a herd of deer:

“…Desirous of killing one of them for food, I hid myself in the bushes, and on a large one coming near, presented my piece, which missed fire on account of the priming having been wetted…” (Armour, Attack…, 88)

But as so often happens, the woodsman involved never explains what he did to remedy the situation. As living historians, we all find this lack of explanation maddening, but over time, bits and pieces of information from other writers hint at why the author left out the details. Most often the remedy of the day was so common it did not require wasting words on a step-by-step analysis.

A number of years ago, another traditional black powder hunter and I engaged in a deep discussion about Northwest trade guns. The subject turned to unbreeching the barrel to clear a wet load. Karl’s research sources are impeccable and extensive. He stated that a number of 18th-century woodsman implied they unbreeched their arms from time to time, but that he had never found a written source documenting the practice.

In his quest, he had spoken to a number of knowledgeable individuals who collected and studied the arms of the fur trade. One in particular told him unbreeching a smoothbore in a wilderness setting would not be that hard, because the breech plugs had much coarser threads than a modern reproduction. He said he did not doubt his source, but tempered that statement with a desire to verify it with primary documentation.

He became ecstatic when I offered two passages from Jonathan Alder’s captive narrative, a source he had not yet read. There are problems with the Alder journal. The original manuscript is lost and/or destroyed. The accepted version is a transcript taken from one written by his son, Henry Clay Alder, based on Jonathan Alder’s public telling of his captive experiences. That said, the commonality of unbreeching a barrel flows through both passages. The first deals with Native American superstitions and the second a personal confrontation over some lost hogs:

“The Indians have a great many superstitions and prejudicial notions about things and one is in regard to the wolf. In all kinds of hunting, you are liable to shoot at game and miss. If an Indian shoots at a bear, deer or buffalo and misses, he thinks nothing of it, but if he shoots at a wolf and misses, he thinks that the wolf has put a spell on his gun that will last for five or six moons—your gun will shoot wide for about that length of time before the spell wears off. You are liable to miss and lose a great deal of your game in that time unless you unbreech your gun and scour and wash it thoroughly clean. I have often seen them unbreeching their guns and asked them what was the matter. The answer was ‘Well, I shot at a wolf the other day and I guess I must have missed him, for my gun hasn’t shot right since.’” (Alder, 95)

“Presently, he came out with is gun but turned and walked from me and tried to fire off his gun, but he had got the load wet, and his gun wouldn’t go off. he went back into the house and took the barrel out of the stock, unbreeched it and took the load out. Then he cleared the barrel, put it together, and reloaded…” (Ibid, 132)

At the 2017 Midwest Rendezvous held at the Grand Valley Cap ‘n Ballers™ home grounds in Hopkins, Michigan, Larry Horrigan demonstrated the skills of a frontier gun maker by building a Committee of Safety musket start to finish by hand using antique tools and technology. While he was boring and tapping the tang screw, he told several bystanders how he acquired the original, late-1770-era, smooth-bored musket barrel for forty dollars.

The barrel had been converted to percussion ignition, and Horrigan told of how he cut off the barrel just before the nipple area and “installed a new breech plug with a finer thread.” His comment started a discussion about the coarseness of the old breech plug threads versus the modern. Larry said he still had the breech plug he cut off, and I asked if I could inspect and photograph it.

The barrel had been converted to percussion ignition, and Horrigan told of how he cut off the barrel just before the nipple area and “installed a new breech plug with a finer thread.” His comment started a discussion about the coarseness of the old breech plug threads versus the modern. Larry said he still had the breech plug he cut off, and I asked if I could inspect and photograph it.

After making an unexpected trip to his shop later in the afternoon, Larry said, “Hold out your hand.” When I did, he dropped the cut-off breech section with the old plug in my palm. “You can have it,” he added with a broad smile.

The threads are coarse and heavy, and I’m sure a machinist would get very technical. For my purposes, I can state the breech’s bore is .720-inch, the plug is .805-inch across, cut nine threads to the inch. A modern breech plug for that size bore would have about fourteen threads per inch.

This is just one original smoothbore breech and plug from the 18th-century. It is military in nature and not of Northwest gun breeding stock. It is one lowly example, but it adds credence to Karl’s speculation and affords some insight into the possibility of unbreeching a gun in the backcountry of the Old Northwest Territory. I feel blessed that Larry Horrigan saw fit to gift me with such an unexpected treasure. Thank you, kind sir!

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to Gifted with an Unexpected Treasure