Canada geese ceased honking at the first shot. A few minutes later a second shot, which sounded like it came from the far hillside, echoed up and down the River Raisin. An anxious thumb rubbed the Northwest gun’s jaw screw. The dangerous intrusion whisked away the cool morning’s pleasant, drying-leaves fragrance, or at least conscious thought of it. Lips grew parched. Neck hairs twitched. Movement in the thick bottoms heightened concern.

Within a minute, two does bounded from the tangle of fallen trees and swamp grasses. The spooked deer held to the low ground, circled a wooded knob, then loped up the first steep hill east of the river bottom. The pair paused near the crest. The largest looked back, the youngest gazed over the hilltop. Satisfied no danger lurked close, the two whitetails walked over the hill and out of sight.

Within a minute, two does bounded from the tangle of fallen trees and swamp grasses. The spooked deer held to the low ground, circled a wooded knob, then loped up the first steep hill east of the river bottom. The pair paused near the crest. The largest looked back, the youngest gazed over the hilltop. Satisfied no danger lurked close, the two whitetails walked over the hill and out of sight.

Not too long after, two blue jays swooped into the bottoms. One gripped an upper branch of a yellow birch, the other landed in a stunted maple. “Swip-it! Swip-it!” the bird in the birch sang. “Swip-it! Swip-it!” the other answered. The forest sentinels showed no concern from their lofty perches on that October morn in the Year of our Lord, 1795.

“Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu,” a crimson cardinal flew to a nearby witch hazel. Chipping sparrows once again spoke. A fox squirrel chattered, then eased along a red oak limb. But the resumption of the morning symphony failed to erase the reality of the two shots—perhaps one woodsman, perhaps two or maybe more?

Buffalo-hide moccasins withdrew, not up and over the hill as the deer escaped, but rather slow and cautious to the east, keeping to the low ground, tree-to-tree. Like the deer, a long pause at the tumbled-over hollow oak discerned no danger; a similar reckoning at the broken hickory alieved additional fear.

The returned white captive’s course struck the low trail that followed the edge of the nasty thicket. The thicket’s tangle all but eliminated an ambush from the right and afforded a quick retreat route, should the need arise.

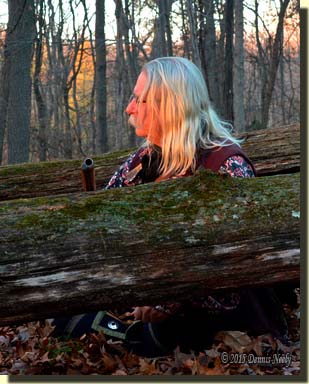

A thin strip of land separated the northeast corner of the nasty thicket from the great huckleberry swamp. And in a like manner, an ancient deer trail skirted the east side of the swamp’s cut bank. The morning’s still-hunt progressed north a mere forty paces. It was there that Msko-waagosh sat with his back to a rum-keg-sized maple and surveyed the steep hillside for a wild turkey dinner…

Location, location, location…

Pine trees with snow-covered boughs circled a clearing that appeared six, maybe eight acres in area. A snowshoe trail entered the clearing at the southwest corner. A brown-clad woodsman, a ranger from a western settlement burdened with pack, blanket and fowler, stood stoic a bit northeast of the clearing’s center. Other pictures in the magazine article showed this forest wanderer many paces out in the open. A foot of snow, snowshoes and heavy gear made escape impossible.

A fellow traditional black powder hunter and I discussed the images some days later. Our opinion was the same; if mischief was afoot this poor ranger was a dead man. I got to thinking about that conversation, randomly pulled magazine copies from the shelf and began thumbing through the pages, looking at the photos from a self-preservation perspective.

Now I realize magazine photos are intended to showcase the subject presented, and they may not depict a living historian’s true practice in the woods. I myself have “adjusted” an image for easier reader recognition. For example, years ago I penned an article that dealt with using natural cover. All of the snapshot images had to be reshot, because my alter ego hid too well and couldn’t be seen. I sat more in the open than i usually do.

But in rummaging through the magazines I noticed a discrepancy in re-creating a host of historical characters, from New France to the Rocky Mountain fur trade eras. For some reason, living historians love to walk out in the open. And as my friend and I discussed, they are doomed to an early, period-correct death.

I sometimes hunt with a ranger out of Fort Detroit. Our time periods clash, and I am working on overcoming that anomaly, but my hunting partner tries hard to adhere to Robert Rogers Rules of Ranging.

“Rogers Rules,” as he calls them, address a mix of military protocol and woodland survival skills. They represent well-thought-out common sense based on actual forest experience. Rogers speaks of how to progress through the wilderness, the importance of limiting footprints or evidence of your travels, how to engage or avoid an enemy and guidelines for pursuing an enemy or effecting a safe retreat.

Late one afternoon, my hunting companion shot a young deer. He field dressed it, dragged it out and had it loaded on his vehicle by the time we rendezvoused after dark. Early on in my hunting career, a respected mentor told me to always take time to study a deer’s flight path. Wanting to do the same with this deer, I asked the location of the kill.

The next morning, I hunted as usual. About 9:30, I decided to seek out the gut pile from the deer and backtrack it. I searched the general area he described, and an hour later I found the remnants of the pile, dragged a ways from the death site by coyotes.

After finding the death site, I back tracked the blood trail, keeping to one side so as not to leave any footprints. The ranger had done the same. I only saw the faint curve of a Ligonier-style moccasin once in over one hundred yards. And despite this care, I feel Robert Rogers might have been a bit apprehensive that a two-inch curve remained—and was discovered.

Whether engaged in a traditional hunt, ranging about the glade on a scout, or simply enjoying a stroll in the woods in period-correct garb, an 18th-century context of self-preservation should always be present and woven into the fabric of any historical simulation. In my experience, keeping to the shadows, resting behind trees or windfalls and choosing a path with a minimum of exposure is better than charging across an open area in plain sight.

Whether engaged in a traditional hunt, ranging about the glade on a scout, or simply enjoying a stroll in the woods in period-correct garb, an 18th-century context of self-preservation should always be present and woven into the fabric of any historical simulation. In my experience, keeping to the shadows, resting behind trees or windfalls and choosing a path with a minimum of exposure is better than charging across an open area in plain sight.

There is no question that such a course of travel requires more steps and will take more time. When I get in a hurry, I stop and remind my alter ego that the journals of my hunter heroes contain no references to checking their cell phones to see what time they were supposed to meet the fort commandant or the local North West Company trader. To the contrary those journals reference pitching camp after taking game late in the day, rather than returning to the homestead or village. That was the habit of forest tenants.

But the best path is the safest path, and that course must be chosen with full consideration to the circumstances as viewed from 1795, not 2015. Today we speak of “location, location, location” as it applies to tree stands, food plots and of course, real estate. Please keep in mind that reference is framed in a modern sense.

As traditional black powder hunters, our obligation is to re-create, as close as possible, a chosen time from long ago. If a gunshot rings out in a living historian’s wilderness Eden, how is that significant to the character portrayal? If a ranger snowshoes across a clearing, what impact will that action have on his survival chances? Perhaps we need to draft a new meaning for “location, location, location,” one that takes into account the need for self-preservation in an 18th-century sense. That is the question those magazine images present…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

2 Responses to Drafting a new meaning