A chilly breeze held mosquitoes at bay. Light dew glistened on greening grass. The autumn olives’ pungent perfume filled the glade with expectation. Damp elk moccasins pressed north, angled west, then crested a flat-topped knoll. That May, in the Year of our Lord, 1794, was colder than normal but pleasant for chasing wild turkeys.

“Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu,” a crimson cardinal twittered as Msko-waagosh’s bound blanket dropped to the ground in a fresh-scrapped nest behind a wild cherry tree. A tom gobbled in the distance, off to the west, just over the ridge crest that loomed beyond the big swamp.

A lone Sandhill crane winged south, silent, majestic, determined. Three black crows flew low over the cedar grove, bent on the River Raisin’s bottomlands, anticipating the day’s opening melee.

“Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…”

An unexpected head popped up, fifty paces distant, beyond a dried and broken-over patch of the prior summer’s nettles. The gray head disappeared, reappeared, then slipped away again, all the while venturing southeast of the crooked-trunk cherry tree with the two cedar trees growing beside it.

Years before, judicious blows of a tomahawk cleared the lower, dead branches of the cedars, creating a curved haven that half-hid the returned white captive. Msko-waagosh did not budge, but his thumb massaged the firelock’s jaw screw with great anticipation.

“Whit, whit, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu, tsu…”

The hen came into full view at thirty-five paces, pecking, inspecting, herky-jerking along, following its usual routine. The hunter’s task was to allow that bird to pass, and any other hens that accompanied it, in hopes a fine gobbler strutted not far behind.

Brown eyes squinted. Breaths grew short and controlled. Purple legs marched closer and closer. Blood surged through tense arteries. The fowl never stopped or looked about, much to the hunter’s delight.

The cardinal’s morning song continued, but the intense concentration of that moment shut out the melodious distraction.

A dozen or so trade-gun lengths away, half-grown green shoots mixed with knee-deep, dead prairie grass. The bronze-backed beauty melted into that thick tangle. The gray head popped up now and again, marking the hen’s path through the tiny clearing, angling east and off into oblivion.

Sun rays broke over the jagged tree line. Two deer wandered by. Once they walked off, two more appeared. An hour or so passed with no inkling of a gobbler existing in the glade. Cardinals came and went. Geese winged from the River Raisin. Sandhill cranes chortled. Black demons cawed and screamed. But no tom ever followed that hen.

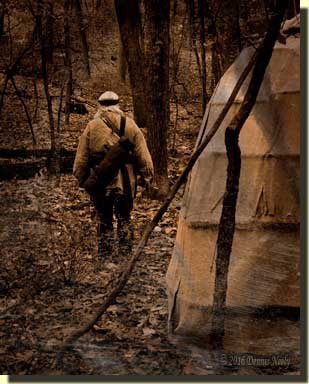

The returned white captive scrambled to his feet. He gazed about, but saw nothing of interest. In one swift movement, his bedroll, bound with a leather portage collar, flew over his shoulders. He adjusted the headband across his breast, checked the Northwest gun’s prime and walked off to the north…

Oh, Dear…Inconsistencies Pop Up…

A couple hours after Friday’s post, “No red, no snood, no gobbler…,” an email from my great friend, Lt. Darrel Lang, popped up in my inbox. I needed a break from writing, so I opened it.

Now usually Darrel’s emails include a link, photo or topic that begs further discussion. In truth, we both just love to talk about living history, re-enacting and traditional black powder hunting so we look for whatever excuse we can find to “venture back.” With respect to Friday’s post, our discussions most often fall into the category of “like-minded individuals.”

Lt. Lang’s historical persona is that of a ranger mustered out from Joseph Hopkins’ Company of Rangers after the siege of Fort Detroit in 1763. We hunt together, when we can. Over the course of a couple of deer seasons a clear inconsistency existed between Lt. Lang’s portrayal based in 1763 and Msko-waagosh’s existence in the mid-1790s. The solution to that dilemma pushed me to embark on my third persona, Mi-ki-naak, a returned white captive living and hunting around the River Raisin’s headwaters in the fall of 1763.

Darrel’s cheery beginning, “Good Morning,” followed by “I read your post this morning, a good way to start the day,” started my day our right, too. In his quiet, unassuming manner, he continued with “I had a couple of observations…” Knowing Darrel as I do, when he speaks to a living history topic, a re-enactor had best listen to his wisdom and advice, especially if it involves one of my portrayals. I took a deep breath and read on.

He noted that I had written from the perspective of Msko-waagosh, then part way down in the story I referred to my alter ego as “The woodsman…,” which Darrel stated confused him a bit. He re-read the passage. To a professional writer, re-reading to grasp an idea, objective or mental image on the part of a loyal reader points up poor communication structure—a definite failure.

“That’s not a term I would use to describe a native or a white captive,” he wrote. “It made me think that the character of the story changed…” Ouch…

I dialed as I read on. I called up my research outlines for the narratives of John Tanner, Jonathan Alder and James Smith, one at a time, as our conversation unfolded. A search for the word “woodsman” resulted in nary a single reference among the passages deemed important. I wasn’t surprised, because I knew he was right.

“To me,” Lt. Lang said, “a woodsman would be a hunter the likes of Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton, or Hawkeye…” The ensuing give and take brought light to the fact that so often the “returned captive” was a misfit among the folks of the settlement or station, tainted by the experience, viewed as part savage, to use the common phrase of the era.

The hour or so we spent on this topic changed my perspective on both Msko-waagosh and Mi-ki-naak. My emphasis has always been on the intricacies of the simple pursuits themselves, undertaken within the umbrella of documented, historical context. But slop-over from the current generation’s political correctness fetish toned down the realism and authenticity that these characterizations need with regard to social standing. The material culture is correct as to location and time period; the interpretation with regards to life station, and communicating that understanding, needs work.

And therein lays the crux of my reference to a constant reliance on a specific process of self-evaluation as one’s best understanding of a forgotten lifestyle improves and grows. Yes, document-based research and hands-on learning in the wilderness classroom move a portrayal forward, but so does contributions and observations from like-minded, knowledgeable living historians, like Darrel Lang and a host of others. I am and will be a better traditional black powder hunter, because he took the time to express a couple of simple impressions.

And I can’t overlook his second observation: “…you called Red Fox’s Northwest gun ‘Old Turkey Feathers.’” Oh, my, another inconsistency. “I’ll try not to let that happen in the future,” I pledged. Subtle awareness of an overlooked detail is a powerful motivator.

“Well, the reality, especially from a new reader’s perspective,” Darrel said as he tried to soften the blow, “is that you wouldn’t know that it was the same gun. A long-time reader would know it, and to me it stuck out when I read the story. I found it confusing as to which character you were writing about.” Forty lashes still stings, even when administered with a wet noodle.

Here again, a hand-me-down has weaseled its way into my ever-evolving portrayal of a returned white captive. To some degree, I have been a “one gun guy” for four-plus decades. “Old Turkey Feathers” is my go-to gun. That smoothbore earned its moniker more than thirty years ago and it belongs to the nameless woodsman who provides sustenance to Samuel the Trader’s meager post.

But in time-traveling reality, the Northwest trade gun that Msko-waagosh used was borrowed, which is inconsistent with most period documentation. Any hunter with a modest amount of skill, be he a Native American or a returned white captive such as John Tanner, harvested enough peltry to purchase his own arm. If he didn’t, he starved and certainly never dictated a book of his misadventures.

As soon as I got off the phone, I made a bee-line for the gun parts stashed in a corner of the re-enacting clothes closet. Ten or so years ago I purchased a Northwest trade gun parts assortment someone barely started. The bore mics .600-inch, which doesn’t match any of my smoothbores or round ball molds. The barrel is 42-inches long, not 36-inches, which I favor for heavy brush hunting. The lock is different from my usual choice, too. I think that is why it still cowers in the closet.

But “different” is good in this case. The finished trade gun will be period-correct, but different from “Old Turkey Feathers” or Mi-ki-naak’s French fusil. Unfortunately, I don’t have time to begin work on this gun, but if I give up my two hours of television each night, maybe… Big sigh…guilty as sinned…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

4 Responses to Big sigh…guilty as sinned…