Silvery dew drops splashed. Wool leggins whisked north. Elk moccasins whispered along an earthen doe trail. That course led to an overgrown wash and a skinny box elder tree that afforded a commanding view of a tiny break between the cedar trees and open prairie grass.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!”

Msko-waagosh, the returned white captive who learned his woodsy skills from his adoptive Ojibwe family, slid the leather portage collar over his head. The rolled and bound blanket dropped into a grassy nest behind the box elder. The Northwest gun rested across his lap with the muzzle on the left side of the trunk. The air held a hint of fermenting deer droppings mixed with the spring freshness of growing greenery and budding cherry trees.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!”

Two gobblers bantered from the treetops on the hogback ridge, some distance west of the clearing he called “the meadow.”

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!”

Chilly fingers rummaged in the shot pouch, seeking a single turkey wing bone, then reconsidered the quest. A long silence prevailed followed by a lone, muffled half-gobble, “Obl-obl!” from the ridge crest, south of the roost trees.

“The birds are on the ground,” Red Fox mouthed to no one. His thumb traced impatient circles on the hammer’s jaw screw. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” he continued.

Second thoughts circled about the skinny, box elder. On only two occasions, early-morning gobblers were seen at the east corner of the meadow; more often on the west or south side.

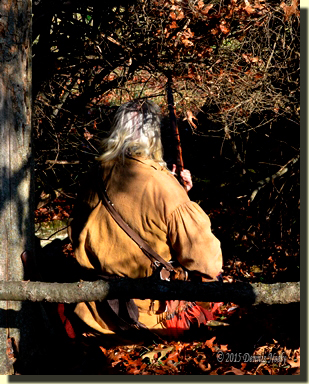

If usual habits prevailed, the gobblers, and maybe a hen or two, should be coming down the ridge’s east face, approaching the crossing trail at the swamp’s narrows. The misgivings won out. The woodsman got to his feet, snatched up the bedroll, slung it over his left shoulder and started off with long, gentle strides.

Hustling moccasins swished into the sanctity of the first layer of cedar trees. Half hunched over, the deathly shape kept to the shadows, then struck a known trail. A mature doe, standing upwind amongst a cluster of red oak trees, watched with perked-up ears. The woodsman’s course reached the meadow’s northwest corner. The doe shook her head and walked off toward the big oak with the broken-down limbs.

Many cedar trees to the south, a favored dead oak stands. Brush about its base was hacked away with judicious blows of a post hunter’s belt ax the year prior. The right amount of grass, barberry and underbrush circles that tree—enough to hide in and still afford a decent chance at a fanned and strutting wild turkey.

“Obl-obl!” The half gobble came from down the hill, on the meadow side of the big swamp.

The woodsman dug the wing-bone from his pouch, then sucked once. “Arrkk,” soft, subtle, beseeching with a bit of authority. The smoothbore’s muzzle eased in the direction of the last gobble.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl! Obl-obl-obl-obl!” The tom hollered from the edge of the gully, a different one that started on the north side of the meadow. The response continued, drowning out the short chortles of Sandhill cranes feeding somewhere off to the east. Geese honked in the distance.

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl! Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!”

Twice the tom started to ascend the hill. At best, he would enter the meadow to the east of the gully, closer to the skinny box elder than the favored, barkless oak. Two Sandhill cranes appeared over the eastern tree line, wings set, coasting into the grassy clearing’s center. The birds all but stopped midair, flapped twice and took the usual three or four long-legged steps upon touching down.

A glimpse of bronze feathers slipped through the half-leafed-out barberry bushes to the right of “Old Turkey Feather’s” muzzle. Msko-waagosh squinted. He touched the trigger as his thumb drew the sharp, English flint to attention, avoiding the loud click of the sear bar dropping into the tumbler. A gray head popped up; no red, no snood, no gobbler…

Making a Choice, Hustling Forward

A line squiggled across the journal page, just after the big move to the meadow’s west side. I often do that, change thoughts in the midst of time traveling. When it happens, squiggly lines mark the beginning and end of the transgression. I have other little scribblings in my journal—funky characters, kindergarten sketches and/or strange symbols. They only have meaning for me, the writer. My kids can have fun figuring my methods out, once I’m gone. I don’t plan on leaving notes to explain my notes…

But the intrusion that morning was a notation that I had “completed Msko-waagosh’s shot pouch two nights ago.” The pouch is based on a couple of Odawa examples in museum collections. The bag is not an exact copy, but rather a utilitarian accoutrement that mirrors the general style. “Affixed a temporary strap to the bag…maybe it will bring me good luck.”

Msko-waagosh used a “loaner bag” when the personification first came to life. Creating a new character is exciting, but a common stumbling block is assembling the clothing, arms and accoutrements necessary to cross time’s threshold in a meaningful manner as an alter ego. I am of the opinion that the best way to develop a persona is to just be that person, now, not later.

As living historians read through a long-lost journal, they become enamored with the author or some other character in the narrative. The interest grows, but they find themselves bogged down with the research and then the assembling of the necessary material goods. Two years, maybe three years down the road they have yet to acquire or make all of the clothing and accoutrements they deem “important to start.” And worse, they never set foot in their 18th-century Eden as their version of the “historical me.”

With time, interest wanes. What goods this not-yet-born person owned find their way to a trade blanket or a forum posting. In essence another re-enactor benefits, so we would hope. In truth the goods hang in a closet, because an existing persona’s broken-in garb gets grabbed first, more out of habit than conscious thought.

There is no right or wrong way to develop a history-based persona, within reason, of course. As knowledge grows, so does the character. That understanding can come from document-based research, from hands-on lessons in the wilderness classroom or from the exchange of information among like-minded individuals—or any combination thereof.

Mixed with this learning is the ongoing process of self-evaluation based on one’s best understanding of frontier survival within the context of a chosen time period, location and life station. Sometimes a discovery requires an immediate adjustment, and other times puzzle pieces must accumulate until a clearer picture emerges. This is the joyous exhilaration derived from living history and traditional black powder hunting. What a blessing!

So on that May morning, in the Year of our Lord, 1794, Msko-waagosh hunted with his new pouch. A buckskin strap attached with a simple thong punched through the back offered a make-do remedy that was a thousand times better than the hand-me-down bag. The pouch at his side was his, a part of the emerging historical me, viewing life through the eyes of a returned white captive in the 1790s.

Taking those first, feeble steps down the path to yesteryear, rather than waiting until the entire persona was fleshed out, facilitated the creative process. In many instances, the hand-me-downs pointed out glaring errors, omissions and immediate needs with respect to the historical record as it applied to a captive who mastered woodland skills under the tutelage of an adoptive Ojibwe family.

Hands-on, wilderness classroom lessons tested each article of clothing, each accoutrement as they became available for use. By the time the permanent strap was beaded, the pouch was an integral part of the person called Msko-waagosh.

Yet, when the woodsman arose from behind the skinny box elder, slung the bedroll on his shoulder and hustled off into the shadows, the new shot pouch disappeared in the switch. Not that it was lost, misplaced or left behind, but rather in the sense that the buckskin pouch flowed along with the move, a part of the persona, a part of the action, a contributing artifact in the midst of a time-traveling adventure.

And what of the gobbler? The hen milled about in the underbrush, then uttered a single cluck, “Arrkkk.”

“Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl! Gob-obl-obl-obl-obl-obl!”

The tom marched up the hill, sounding off as it slipped through the shadows and navigated around the tight-growing cedar trees, much like Msko-waagosh had done over an hour before. A red head with a white pate appeared at the edge of the clearing. The roll of the knob hid the bird’s body. The red snood swung side-to-side. The tip of his spread fan teased and taunted. The tom pirouetted, gobbled and danced some more. His head vanished behind the knoll’s crest. When he stopped yodeling, the hen started walking around the meadow.

There was a silver lining to this display: the long-bearded gobbler never came close to the skinny box elder, either…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.