Windshield wipers thumped side-to-side. About Wapakoneta, Ohio, I considered turning back. A quick glance at the odometer and some simple arithmetic dispelled that folly; I was half way to Friendship, Indiana, and my first visit to the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association. Construction barrels narrowed I-75 to one lane south of Dayton, but over the years I found that was most often the case. The “flip, flip, flip…” of the wipers made the run from Dayton to Cincinnati drag on, which only added to the anxiety of this first-time adventure. Then the big green sign for the westbound I-275 bypass brought new hope.

I remember seeing the exit for Cleves, Ohio. The name caught my eye. A day later, a gent by the name of Max Vickery explained to me Mr. Lubekeman, a patron of the NMLRA who owned the Trius Trap Company, located in Cleves, OH, donated the traps that made Shaw’s Quail Walk possible. I think about Mr. Lubekeman’s generosity every time I pass that exit.

The rain picked up through Lawrenceburg and Aurora, Indiana. Night always seems darker during a rainstorm. I was surprised when US-50 turned into a divided highway. The driving directions were scribbled on a folded piece of computer paper with no mention of distances. Indiana State Highway 262 lasted one block before I turned west on SR-62.

From looking at the map, I knew Dillsboro wasn’t that far down the road, but I wasn’t prepared for the winding road that was little more than a paved two-track beyond the village limits. The farther out of town I got, the closer the big trees grew to the road’s edge, and the sharper the twists and turns became. I slowed down. The wipers’ “flip, flip, flip…” drowned out the scratchy radio station. I saw no life along the road, no lights in windows, not even a wandering raccoon or possum.

Two or three mercury-vapor lights illuminated the backsides of a couple of homesteads at Farmers Retreat. A single bulb burned over the entrance to the local church. Tense fingers gripped the steering wheel. “You have to be close,” I remember thinking. Then the Dodge rounded a bend and dropped down into the Laughery Valley.

At the base of the long hill, I entered what appeared to be a county fair midway. Lights blazed under vendor tents and yellow or red ones flashed around food concession signs. There was no mention of the Friendship Flea Market in Muzzle Blasts; I had no idea what I just drove into. Then, over the bridge, on the west side of the rows of vendors, I spotted smoke rising under floodlights that lit the trees on a steep hillside. An orange clay pigeon rose up, then disintegrated. The first boom of a muzzleloader pleased my ears.

The pickup turned at the main entrance. The log camp shack stood to the right. After stretching my legs, I registered, paid for a weekend worth of primitive camping and headed for the concrete bridge that leads to the primitive campground. I laid the red silk ribbon used to mark my shelter on the seat over top of the map book. The rain eased to a light drizzle, but didn’t dampen my enthusiasm and exuberance.

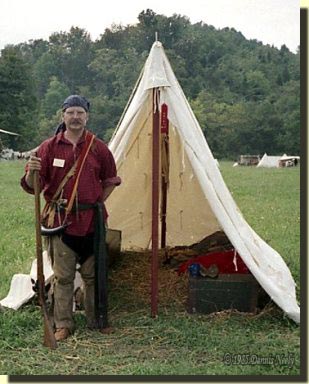

With the wedge tent’s poles placed just-so on the ground, I drove four steel stakes. When I picked up the new wedge from Bill and Lila Walters, Bill explained how to set it up alone. I still remember the damp, stick-to-the-skin feeling of the wet shoulders of my new, red, calico trade shirt. I still have that shirt; the shoulders are sun-faded with a blood stain here and there.

With the wedge tent’s poles placed just-so on the ground, I drove four steel stakes. When I picked up the new wedge from Bill and Lila Walters, Bill explained how to set it up alone. I still remember the damp, stick-to-the-skin feeling of the wet shoulders of my new, red, calico trade shirt. I still have that shirt; the shoulders are sun-faded with a blood stain here and there.

Anyway, the tent was up, braced and secure in a matter of minutes, much to the amazement of my nearest neighbors, who did offer to help. A new voyageur’s cassette, made special for the first trip to Friendship, found its way into the tent. I broke open the bale of straw that made the long trip in the pickup’s open box and fluffed up a thick bed to one side of the wedge. An oil-cloth bedding sack came next with a crimson-colored Whitney three-and-a-half-point trade blanket next.

After parking the Dodge, I walked up the hill to my humble abode and introduced myself to the two fellows camped just up the south. We talked for a few minutes, then I headed to bed. Bill told me not to worry about rain as the canvas’ threads would tighten when wet. I fell asleep to the joyous pitter-patter sound that always reminds me of Friendship.

Learning the Hard Way

I didn’t spot the spiders—the big brown fuzzy ones—until Saturday afternoon. We call them barn spiders here, but that makes no difference. The straw bedding harbored several family reunions worth of the critters. The wilderness message was loud and clear: Don’t use loose straw for bedding.

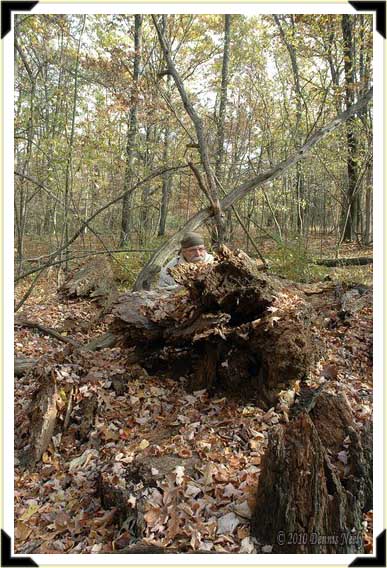

I have used neither straw nor hay since. On a couple of occasions gathered dry leaves afforded a one night bed. Temperature has some bearing, as does humidity or rain. For example, the “cedar bush shelter,” patterned after one in Meshach Browning’s narrative, sported a deep leafy bed. Within a week the fluffy leaves gathered moisture and withered together into a flat, wet, rotting mush—just like the leaves scattered about the forest floor did.

The oil-cloth bedding sack was never used again, either. I experimented with two heavy wool blankets, one for cushion and one for warmth. The ground was hard on my shoulders then, and it still is now, even when I cheat and add an extra blanket. I mumble “discomfort is period-correct” when I roll over at night, which is usually followed with a contented smile.

Now and again, an old journal will mention some natural material used for bedding, such as Daniel William Harmon, a young, North West Company clerk, did on his journey out to the interior. Harmon writes on October 8, 1800:

“To make a place to lie down the people scraped away the Snow & lay down a few Branches of a species of Pine we find every where in this part of the World, and then upon the top of that, a blanket or two, and where after a Day of hard labour I am persuaded a person will sleep as sound as if on a Feather Bed.” (Harmon, 33 – 34)

Now I tried pine boughs a couple of times, once in the Huron National Forest in northern Michigan. The finger-sized branches seemed to position themselves in such a way as to press against a bone with enough intensity to require removing the two blankets and re-laying the boughs. I got cold that night. The next night I went back to sleeping on the two blankets only.

On a fall turkey hunt, maybe 25 years ago, I spent a fair part of the night beneath a leaning jack pine tree. Exposed roots formed an adult-sized cradle filled with soft green moss. I slept hard until about 2 a.m. when a poacher’s spotlight swept over that area. After a not-so-distant shot the beat-up pickup with the blown muffler came back and again lit up my little corner of Eden. After they were well gone, I rolled my blankets, hiked to my pickup and ended up sleeping under a yard light in the parking lot of a local church.

I laughed the other day when I recounted that first trip to Friendship, the straw bedding and the million-plus spiders the golden thatch attracted. A couple of gray-beards at a local black powder shoot suggested I take a bale of straw to pad the hard ground. I listened, I tried and I learned the hard way.

I laughed the other day when I recounted that first trip to Friendship, the straw bedding and the million-plus spiders the golden thatch attracted. A couple of gray-beards at a local black powder shoot suggested I take a bale of straw to pad the hard ground. I listened, I tried and I learned the hard way.

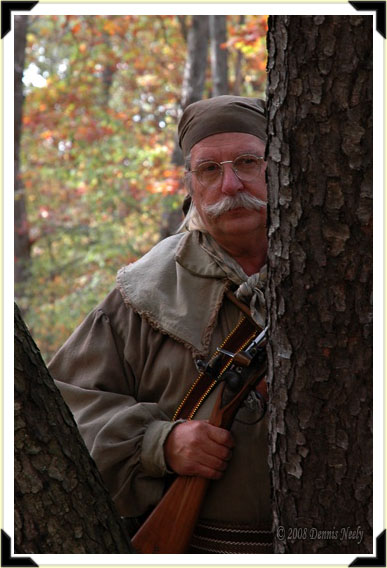

At the next shoot I spoke of the spiders. After the laughing ceased, both said, “That’s why we sleep on Army-surplus cots.” I didn’t remember that bit of wisdom in the original conversation. With that, I also began taking their advice with a grain of salt. I doubt they ever spent a night out in the wilderness classroom, either on a hunt or a trek. And that is where we differed. l learned by trial and error that the best course is to follow the guidance, sketchy as it may be sometimes, of my hunter heroes and experience the 18th-century life in its entirety—period-correct discomforts and all…

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.