Wood ducks whistled. The pair winged straight up, flared to the east, dipped low over the maple point, then glided out of sight over the huckleberry swamp. In less than a minute they circled back, sashayed between the oaks, then landed a trade gun’s length apart on an upward angling oak branch, two trees to the north.

As the sun’s rays crested the next knoll, I began to wonder if a humble woodsman’s presence disrupted their 1795 world—perhaps I was sitting at the base of their nesting tree? I pondered moving. I glanced to the north; the birds were still perched. Through the river bottom’s half-leafed trees, I could see the sun illuminating the hardwoods on the River Raisin’s far bank. Dark shadows still drenched my lair.

Four wild turkey toms bantered nonstop from their roost trees shortly after I arrived—all in those hardwoods. There was nary an utterance on my side of the river, not even a sullen cluck from a lost hen. The gobbling stopped when dawn’s first golden spears touched the hardwood’s uppermost branches. Now and again a muffled gobble teased from the ground as the birds moved farther north in search of hens.

My head eased back against the “yellow oak,” named for the bright yellow cast the exposed heartwood gave off when a main branch broke off, splitting the trunk almost to the ground. A dozen winters grayed the trunk. A large, creamy-white shelf fungus grew to my left. A big black ant zigzagged across the protrusion.

The last gobble added to the morning’s frustration. I peered from inside the forest-green, wool trade blanket and counted seven mosquitoes buzzing about, just beyond my spectacles. The wood ducks circled again, whistling as they passed. I took one last look about, scrambled to my feet and folded the blanket lengthwise. With the blanket draped over my left shoulder, I eased into the cedars and moved closer to the huckleberry swamp.

Mosquitoes swarmed about. Each step of my buffalo-hide moccasins raised another dust-like cloud of blood-sucking beasties. A tiger mosquito weaseled its way under the ruffled cuff of my trade shirt and bit the little finger of my right hand, which gripped the Northwest gun. My left hand released the blanket’s edge and swatted the pest, smearing blood on the back of my hand. It took a great effort to fight the urge to move quicker, but haste would not lessen my misery.

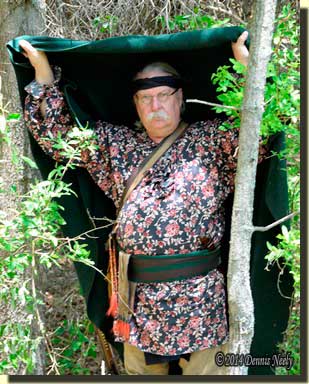

Two thigh-sized young oaks caught my attention. Autumn olive bushes grew about the saplings offering additional natural cover. I leaned the smoothbore against the smaller tree, unfolded the blanket and with my arms spread wide, held it over my head. I folded the blanket about my body, covering it head to moccasins, and sat down.

Two thigh-sized young oaks caught my attention. Autumn olive bushes grew about the saplings offering additional natural cover. I leaned the smoothbore against the smaller tree, unfolded the blanket and with my arms spread wide, held it over my head. I folded the blanket about my body, covering it head to moccasins, and sat down.

My right hand retrieved the trade gun and rested it across my lap. My fingers pulled a wing bone call from the shot pouch; I laid it on a white oak leaf to the right. I adjusted the blanket, leaving a narrow slit to see through.

I sat for a short while, as I so often do. Satisfied I had not spooked a bird, I dragged a single, soft cluck on the hunt-polished wing bone. About ten minutes later, I clucked again. I waited, amusing myself by watching three sassy fox squirrels frolic in the two big oaks in front of me. A bit later, I counted 14 mosquitoes jockeying about on the front of the blanket in search of an advantageous position at the feed trough. I wondered how many followed a similar pursuit on my back and sides. Throughout the morning, a tom turkey never answered my amorous requests; a curious hen never investigated; but from the roost gobbles, I expected that.

A New Lesson in the Wilderness Classroom

It seems that winter’s lingering cold upset the wild turkeys’ spring mating rituals at the headwaters of the River Raisin. A dryer than normal March and April aided this woodsman in his simple pursuit, but a few days of heavy rain in mid-May spawned a massive hatch of blood-sucking beasties. Mosquitoes and spring turkey hunting go hand in hand, but the last week or so has been much different—“unbearable” is the word most modern hunters are using to describe this plague.

But mosquitoes or not, a traditional woodsman cannot put food on the table without venturing into the wild and sitting still enough to bring a wary gobbler close in. The current conditions are the worst I have seen in at least the last two decades, so what must a humble time traveler do to survive in the Old Northwest Territory?

In researching historical methods of dealing with mosquitoes, I found a passage in James F. O’Neil II’s first volume of Their Bearing is Noble and Proud. This passage is attributed to a French soldier’s journal about the time of the French and Indian War:

“Mosquitos are the most troublesome pests. They are called stingers and gnats in Europe. To keep them off, it is often necessary to rub lard on the face, hands, and body; the insects sticks to the grease and dies instantly.” (O’Neil II, v. 1, 27)

I know I have other passages marked that describe using bear grease in place of lard, but none offer a solution that fits my persona or my traditional black powder hunts. I am not aware of any herbal remedies, either, but I expect some existed. At any rate, slathering up with lard or bear grease for a two-hour, early morning turkey hunt is impractical, at least for this woodsman’s circumstance.

As I work on the various aspects of my persona, I keep coming back to Jonathan Alder’s admonition to young Tom Springer. After dressing “a large buck” killed by Springer, Alder decided the two should camp out overnight. When his hunting companion lamented that he had not brought a blanket, Alder replied:

“You ought to have thought of this when you started out…You never see an Indian start out without his gun, tomahawk, butcher knife and blanket.” (Alder, 126)

The first morning of the hatch, swarming mosquitoes drove me from the cedar grove—that was a few days before I sat against the yellow tree. Frustration and disgust washed over me. I stood in the adjacent clearing, sorting through my options. My blanket was rolled, bound with a leather portage collar and slung over my shoulder. I was about to walk away, to give in to the blood-sucking beasties and surrender. In a fit of serendipitous inspiration, I remembered the wool trade blanket.

Up until that moment, the rolled trade blanket represented a polite adherence to an age-old statement of wisdom. Yes, at times I considered it an unnecessary historical prop. But suddenly that common trade blanket took on new importance. Perhaps Jonathan Alder was right. I only thought in terms of the blanket’s warmth. I never considered the protective nature of the thick wool weave. Slung on my back was an accoutrement ready for testing in my 18th-century wilderness classroom.

Anticipating the first laboratory experiment, my buffalo-hide moccasins still-hunted to the north with renewed enthusiasm. I stopped at a small stand of cedar trees where wild turkeys sometimes loaf midday. I untied the portage collar’s long tails, rolled out the blanket and wrapped it about my body, covering every inch of exposed skin, save a little narrow slit for observation.

That morning’s temperature was climbing into the 70s, but I felt comfortable. It was hard to sit still and not swat at the buzzing beasties that hovered about my ears. Watching mosquitoes land on the blanket was a bit unnerving; it took a while to accept that they could not bite. Much to my delight, the blanket held the mosquitoes at bay. An occasional valiant explorer flew through the opening and tried to bite my nose or forehead, but I learned a quick puff of breath, carefully directed, usually blew the invader away.

That morning’s temperature was climbing into the 70s, but I felt comfortable. It was hard to sit still and not swat at the buzzing beasties that hovered about my ears. Watching mosquitoes land on the blanket was a bit unnerving; it took a while to accept that they could not bite. Much to my delight, the blanket held the mosquitoes at bay. An occasional valiant explorer flew through the opening and tried to bite my nose or forehead, but I learned a quick puff of breath, carefully directed, usually blew the invader away.

I am not aware of any documentation for using a blanket in this manner. I intend to spend some time perusing through my favorite journals in search of passages dealing with insects. It’s a subject I really haven’t thought about. I’ve just tolerated the discomfort, accepting the little creatures as an integral part of living and surviving in the glade. But this year is very different, and my alter ego is not willing to give up the hunt. Thanks to Jonathan Alder’s admonition, he doesn’t have to.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.