The Northwest gun’s front sight found a British soldier’s neck. As the death messenger crossed the clearing it would drop, and if true, would strike the Redcoat mid-chest. The black flint lunged. Sparks streamed. Gunpowder flashed. A brilliant yellow tongue thundered from the trade gun’s muzzle. “Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

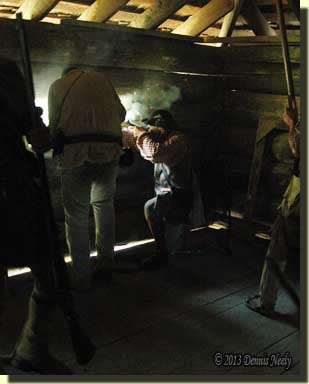

Thick, white, angry murk filled the window. There was no time to feel remorse. I scrambled to my feet and stepped to the right as Jeff Pell knelt and rested his rifled gun on the log sill. In the smoky darkness, gunpowder spilled over the brass measure’s sides. The charge tumbled down the bore. A lead ball followed, rattling in the trade gun’s fouled abyss. A shaking finger shoved a hunk of wadding into the hot muzzle. The wiping stick clattered, then thumped three times.

“BANG!” Jeff’s rifle cracked. Ned Newhart waited his turn as Jeff got up. He looked at me and mouthed “Got one” as he pulled the plug from his horn and began to reload. The bat that had pestered us took wing. In the same instant a pan flashed in the other gun port: “BANG!” The report aggravated the little demon; it circled once, twice, three times, then flew up to a hand-hewn rafter and crawled out of sight. The sulfurous stench of spent gunpowder, old dust and the pungent smell of sweaty woodsmen tingled my nose as I stepped forward.

“BANG!” Jeff’s rifle cracked. Ned Newhart waited his turn as Jeff got up. He looked at me and mouthed “Got one” as he pulled the plug from his horn and began to reload. The bat that had pestered us took wing. In the same instant a pan flashed in the other gun port: “BANG!” The report aggravated the little demon; it circled once, twice, three times, then flew up to a hand-hewn rafter and crawled out of sight. The sulfurous stench of spent gunpowder, old dust and the pungent smell of sweaty woodsmen tingled my nose as I stepped forward.

“BANG!” Newhart’s rifled gun flashed and fired. As he pulled away, I pushed the Northwest gun’s muzzle through the opening while sprinkling gunpowder in the empty pan. My fingers flipped the frizzen down and pulled the English flint to attention as I knelt. A leather-clad knee rolled on the upraised corner of a warped floor board. I scowled, a part from the knife-like pain, a part from a gnawing concern that Indian allies might be among the British advancing on the fort.

Late that afternoon, in the summer of 1795, Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, the white captive who once lived among the Ojibwe, entered the fort’s trading house. Thirty round balls and two handfuls of gunpowder cost four deerskins. My alter ego resisted the trader’s insistence on purchasing a new knife, priming wires or gun worms.

As I walked through the doorway and out into the commons, I saw the questioning stares, the suspicious looks. I feared a butcher knife in the back or a swift tomahawk blow to the temple, administered by a fort dweller who thought I was more Indian than white. I chose not to tarry. As I was about to slip away into the forest a disheveled farmer appeared in the clearing, running hard towards the blockhouse yelling, “British! British soldiers!”

Colonel Roberts took charge and perched on the first tread of the blockhouse steps. He was half-dressed, wearing no weskit over his clean, white shirt and faded-green knee breeches. His leather leggins were buttoned and gartered, and a stately, blue-silk scarf was tied about his collar. “Grab your firelocks, horns and pouches,” he ordered, “and head upstairs.” The Colonel looked straight at me, stern and uncertain. I had no choice but to obey.

The Fort Greenville Match

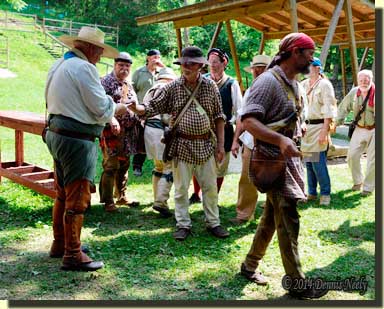

The Fort Greenville Match, Match 656 at the Max Vickery Primitive Range on the home grounds of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association, is one of my favorites. Back in the mid-1990s, a group of living historians and competitive shooters wondered if it was possible to re-create the conditions of a fort under attack using live rounds. Ricky Roberts—I elevated him to “Colonel Roberts” for my own living history purposes—was a member of the original group that founded the match, and he oversees it today.

In June of 1999 their campfire discussions resulted in the first Fort Greenville Match, named in honor of the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in August of 1795. Match 656 is for flintlocks only and participants must be dressed in period-correct clothing. Team members are drawn by lot to avoid stacking a team. There are three competitors to each team.

In June of 1999 their campfire discussions resulted in the first Fort Greenville Match, named in honor of the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in August of 1795. Match 656 is for flintlocks only and participants must be dressed in period-correct clothing. Team members are drawn by lot to avoid stacking a team. There are three competitors to each team.

After reviewing the safety procedures and the rules for the match, the teams ascend the narrow stairs to the blockhouse’s dimly lit second floor. Ricky usually sets the historical tone of the event by telling everyone to “grab your firelocks, horns and pouches and head upstairs.” Participants get pretty somber by the top step. I try to slip back to 1795.

Shooters start with their guns loaded, but unprimed. An arm can only be primed after the muzzle is through the window and pointed downrange. The match time varies, but this year each relay was five minutes. The idea is to get off as many shots as possible in that time period. This year’s target was a nine-inch round steel silhouette on the grassy hillside, a solid hundred yards from the blockhouse.

In a practical sense, loading fast and rushing to the opening in the log wall is a hindrance; a team’s three shooters must develop a rhythm that fosters an even flow to the window. Several of us shoot smoothbores in the match, and we sometimes draw “looks,” because of that choice. A couple years ago, one of my team members asked Ricky if he could switch to another group, because he didn’t want to be “hampered with a smoothbore shooter” on his team.

Yes, a hundred yards at a nine-inch clangor is a poke for a smoothbore, especially in my case, because I rarely shoot beyond my effective distance of 75-paces. As my neighbor Jeff said recently, “you’ve been loading with ‘compost’ for too long.”

It seemed impractical to take a handful of leaves up the stairs—and I question the historical accuracy of that course of action—so I just dropped the ball down on the powder charge. I added a split-apart wad, tamped firm with the wiping stick, for safety. I knew how that load would group out to 50 paces, but I had no idea what to expect at 100 yards, other than it would shoot low. And to be honest, I focused my expectations more on my new alter ego experiencing a unique 18th-century moment than on winning a medal—my apologies to Jeff and Ned.

A New Experience for Msko-waagosh

When I reached the head of the stairs, I moved to the shadows and leaned against the back wall. My persona’s outward appearance was different from the other fifteen woodsmen who defended the fort that day. I’m working on nurturing a mental attitude that reflects the doubting of one’s allegiances.

Now I must note that Melissa Rosemeyer did not dress as a proper frontier lady. She wore a sweat-stained buckskin dress, a sun-faded brown trade shirt, carried a long knife and possesses a reputation for shooting a rifled gun better than most men. To my knowledge, Msko-waagosh was the only captive who had returned to white society among the lot.

In my mind’s eye, I did not see a black-painted steel clangor, but rather an advancing Redcoat. Somewhere between the second and third shot the thought struck me that there might be Native allies among the attackers. In retrospect, I realize that is a major breakthrough in creating the necessary mindset that must accompany each persona we create.

Five minutes ticked by all too fast. After our relay, I again took a place in the shadows with my back to the log wall. My heart was still pounding. The gunfire commenced, releasing a torrent of historical thoughts that pushed me back over time’s threshold. It took me a few moments to return to the 21st-century after Colonel Roberts hollered “Cease Fire!” for the last time.

Once downstairs I asked Tami if she had seen any hits from Old Turkey Feathers. In a rather loud, unceremonious voice she announced that she didn’t think I hit the target once. Much to my surprise, Jeff came over and told me our team had six hits. Ricky looked at the score sheet and asked “team three” to come forward. Ned, Jeff and I stepped up to accept the traveling trophy and our gold medals. The fine shooting of Ned Newhart and Jeff Pell carried the team, no thanks to Msko-waagosh.

Once downstairs I asked Tami if she had seen any hits from Old Turkey Feathers. In a rather loud, unceremonious voice she announced that she didn’t think I hit the target once. Much to my surprise, Jeff came over and told me our team had six hits. Ricky looked at the score sheet and asked “team three” to come forward. Ned, Jeff and I stepped up to accept the traveling trophy and our gold medals. The fine shooting of Ned Newhart and Jeff Pell carried the team, no thanks to Msko-waagosh.

The Fort Greenville Match was the only shooting match I entered at Friendship this spring. On the walk back to camp, expressing her inimitable wisdom, Tami said, “Well, you entered in one match and your new persona won a gold medal. That’s quite an accomplishment.”

“Well, it’s all a matter of perspective,” Msko-waagosh said. “I entered one match, shot five times, missed the target each time and walked away with a gold medal. That’s a pretty dubious claim to fame.”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.

6 Responses to A Dubious Claim to Fame